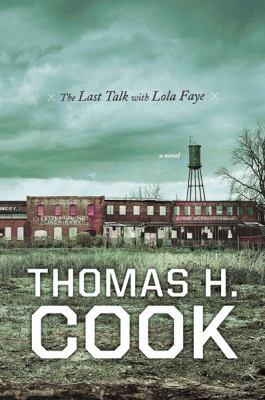

The last talk with Lola Faye

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Victoria | Available |

Browse Related Items

- ISBN: 0151014078

- ISBN: 9780151014071

- Physical Description 275 pages ; 24 cm

- Publisher Boston : Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010.

Content descriptions

| General Note: | "An Otto Penzler book." |

| Immediate Source of Acquisition Note: | LSC 31.50 |

Additional Information

The Last Talk with Lola Faye

Click an element below to view details:

Excerpt

The Last Talk with Lola Faye

So, Luke, what's the last best hope of life?  The memory surfaced as it often did, out of the blue, for no apparent reason: Julia, my lost wife, glances up from something she's been reading, takes off her glasses, and, knowing that nothing will ever open inside me until I answer it, she bluntly poses her question.  I was standing before a glass display case filled with old frontier blankets when this memory last came to me. The blankets were thick and rough, and I imagined those first westward settlers curled up beneath them, whole families pressed together as they waited out the night. How fiercely the prairie winds must have lashed their little wagons, shaking the spindly frames and billowing out the canvas. Later they'd no doubt used these same blankets to ward off the frigid cold that had so ruthlessly whipped the plains, spreading them over the dirt floors of their dugouts, or layering them over their own shivering bodies, where they'd huddled with their dogs as the wind howled outside. How much warmth these blankets must have provided, I thought. How often they must have seemed the only warmth.  It was this sense of physical suffering in the service of some great hope that had once formed the basis for all my human sympathy, the one deep feeling that was truly mine, and that had once fired my dream--boyishly, perhaps, but yet more powerfully for that--of writing my own great books.  In those books, I'd hoped to portray the physical feel of American history, its tactile core: the searing bite of a minié ball, the sting of a lash, the muscular ache of hard labor and the squint of small chores--what it had actually felt like to pick cotton, hew a tree, fire a locomotive, thread a needle made of whalebone, shape a candle by another candle's light. Mine would be histories with a heartbeat--palpable, alive, histories that pulsed with true ¬feeling.  I'd done none of that, I knew, as I turned from that glass case, those neatly stacked frontier blankets. I'd written a few books, the most recent to be published just three months from now, but I'd never created anything that approached the works it had been my youthful ambition to write.  It's one thing to bury an old dead dream, however, and quite another to attempt, again and again, to resurrect a dream you can't let die, which is what I'd done, always beginning with a passionate concept, then watching as it shrank to a bloodless monograph. I'd repeated this process many times, and later that same afternoon, only a few minutes after I'd stood before those frontier blankets, I prepared my desk for yet another run at my old best hope, but stopped and found myself thinking about where it had all begun.  Then, rather suddenly, it came to me, a memory of my mother's wedding ring. Just before leaving Glenville, I'd picked it up and looked at it closely, like a jeweler, recalling all the times I'd seen her delicately remove it before washing dishes because she feared it might slip off and disappear down the drain. At the heart of those memories, I should have felt some gritty aspect of her life: the weight of an iron as she pushed it across a shirt, the oily touch of dishwater, the gooey damp of batter, and if not these, then at least I should have been able to infuse the ring she'd cherished with that power of time and remembrance we trivialize with the phrase sentimental value.  Surely, I should have felt something at such a moment, but tellingly, I hadn't. Unless one could call numbness a feeling, for that was the only sensation I'd actually had, a numbness at the core, everything dry, brittle, dead, all of which should have told me that no matter how many times I tried, I would never write the deeply sentient books it had been my dream to write, that I was, and always would be, as Julia had once said, a strangely shriveled thing.  Standing at my desk, recalling the unfeeling way with which I'd stared at my mother's ring, I heard again her earlier question: So, Luke, what's the last best hope of life?  I glanced out the window, into the chill September rain, and thought again of how life's darkest acts pool and swirl, but never go under the bridge.  So, Luke, what's the last best hope of life?  I'd had no answer then.  Now I do. Excerpted from The Last Talk with Lola Faye by Thomas H. Cook All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.