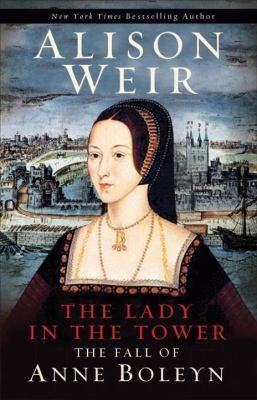

The lady in the tower : the fall of Anne Boleyn

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Victoria | Checked out |

Browse Related Items

- ISBN: 0771087667

- ISBN: 9780771087660

- Physical Description xvii, 434 pages : illustrations (chiefly color)

- Publisher Toronto : McClelland & Stewart, [2010]

- Copyright ©2010

Content descriptions

| Bibliography, etc. Note: | Includes bibliographical references (pages 361-372), Internet address and index. |

| Immediate Source of Acquisition Note: | LSC 34.99 |

Additional Information

The Lady in the Tower : The Fall of Anne Boleyn

Click an element below to view details:

Excerpt

The Lady in the Tower : The Fall of Anne Boleyn

CHAPTER 1 Occurrences That Presaged Evil   Three months earlier, on the morning of January 29, 1536, in the Queen's apartments at Greenwich Palace, Anne Boleyn, who was Henry VIII's second wife, had aborted-- "with much peril of her life"-- a stillborn fetus "that had the appearance of a male child of fifteen weeks growth." The Imperial ambassador, Eustache Chapuys, called it "an abortion which seemed to be a male child which she had not borne three-and-a-half months," while Sander refers to it as "a shapeless mass of flesh." The infant must therefore have been conceived around October 17.  This was Anne's fourth pregnancy, and the only living child she had so far produced was a girl, Elizabeth, born on September 7, 1533; the arrival of a daughter had been a cataclysmic disappointment, for at that time it was unthinkable that a woman might rule successfully, as Elizabeth later did, and the King had long been desperate for a son to succeed him on the throne. Such a blessing would also have been a sign from God that he had been right to put away his first wife and marry Anne. Now, to the King's "great distress," that son had been born dead. It seemed an omen. She had, famously, "miscarried of her savior."  Henry had donned black that day, out of respect for his first wife, Katherine of Aragon, whose body was being buried in Peterborough Abbey with all the honors due to the Dowager Princess of Wales, for she was the widow of his brother Arthur Tudor, Prince of Wales. Having had his own marriage to her declared null and void in 1533, on the grounds that he could never lawfully have been wed to his brother's wife, Henry would not now acknowledge her to have been Queen of England. Nevertheless, he observed the day of her burial with "solemn obsequies, with all his servants and himself attending them dressed in mourning." He did not anticipate that, before the day was out, he would be mourning the loss of his son with "great disappointment and sorrow."  Henry VIII's need for a male heir had become increasingly urgent in the twenty-seven years that had passed since 1509, when he married Katherine. Of her six pregnancies, there was only one surviving child, Mary. By 1526 the King had fallen headily in love with Katherine's maid-of-honor, Anne Boleyn, and after six years of waiting in vain for the Pope to grant the annulment of his marriage that he so passionately desired, so he could make Anne his wife, he defied the Catholic Church, severed the English Church from Rome, and had the sympathetic Thomas Cranmer, his newly appointed Archbishop of Canterbury, declare his union with the virtuous Katherine invalid. All this he did in order to marry Anne and beget a son on her.   It had not been the happiest marriage. The roseate view of Anne's apologist, George Wyatt reads touchingly: "They lived and loved, tokens of increasing love perpetually increasing between them. Her mind brought him forth the rich treasures of love of piety, love of truth, love of learning; her body yielded him the fruits of marriage, inestimable pledges of her faith and loyal love." Yet while some of this is true, in the three years since their secret wedding in a turret room in Whitehall Palace, Henry VIII had not shown himself to be the kindest of husbands.  In marrying Anne for love, he had defied the convention that kings wed for political and dynastic reasons. The only precedent was the example of his grandfather, Edward IV, who in 1464 had taken to wife Elizabeth Wydeville, the object of his amorous interest, after she refused to sleep with him. But this left Anne vulnerable, because the foundation of her influence rested only on the King's mercurial affections.  His "blind an Excerpted from The Lady in the Tower: The Fall of Anne Boleyn by Alison Weir All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.