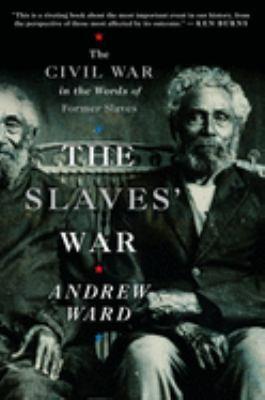

The slaves' war : the Civil War in the words of former slaves

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Victoria | Available |

Browse Related Items

| Genre |

| Biographies. Personal narratives. |

- ISBN: 0547237928

- ISBN: 9780547237923

- Physical Description xiv, 386 pages : illustrations

- Edition 1st Mariner Books ed.

- Publisher Boston : Houghton Mifflin Co., 2009.

- Copyright ©2008

Content descriptions

| Bibliography, etc. Note: | Includes bibliographical references (pages 354-372) and index. |

| Immediate Source of Acquisition Note: | LSC 19.95 |

Additional Information

The Slaves' War : The Civil War in the Words of Former Slaves

Click an element below to view details:

Excerpt

The Slaves' War : The Civil War in the Words of Former Slaves

PROLOGUE "We DoneNow" Fort Sumter * Gladness and Lamentation Well before sunrise on Friday, April 12, 1861, George Gregory joined a group of his fellow slaves on the Charleston waterfront and gazed across the harbor at Fort Sumter's dismal, hulking silhouette. Sumter's commander, Major Robert Anderson, had been holding out since the previous December, refusing demand after demand that he turn the fort over to Secessionist South Carolina. Now his time was up. "Abe Lincoln had sent the word that he going to send provisions to the fort," recalled a local slave named Josh Miles, and "the whole town of Charleston" went down to see "the first shot fired." White Charlestonians darted around crying, "Everybody get back! The fort will fire on the town and kill every person," Gregory remembered. "But nobody care, cause they figure if one going to be killed, they all going to be, and it don't make a difference no-how. And just as the light commence making the sky red, and it's light enough to see who that is standing by you -- BOOM! -- the first gun went off!" from the Secessionist batteries. "The light from it shone in the sky, and made it redder! The war done commence," and all around Gregory "the folks shout, and some cry, and some sing." That morning William H. Robinson was driving his master and a companion to Wilmington, North Carolina, when they heard the booming of cannons "echoing down the Cape Fear river" and across "the broad bosom of the Atlantic." Slapping his hands together with a curse, his master looked "deathly pale" as he turned to his friend and said simply, "It's come." He hastily jotted a note and handed it to Robinson to take back to his mistress. But as was his habit with all his master's mail, Robinson stopped first at the cabin of a literate slave named Tom to hear it read aloud. "We have fired on Fort Sumter," it said. "I may possibly be called away to help whip the Yankees; may be gone three days, but not longer than that." Robinson's master went on to instruct his wife to tell their overseer "to keep a very close watch on the Negroes, and see that there's no private talk among them," and to give two local whites suspected of abolitionist tendencies "no opportunity to talk with the Negroes." Soon after the firing on Fort Sumter, Louis Hughes was waiting with his team outside a store in Pontotoc, Mississippi, when his owner emerged. "What do you think?" blustered master Ed McGee, climbing into his carriage. "Old Abraham Lincoln has called for 75,000 men to come to Washington immediately. Well, let them come," he snarled, "we will make a breakfast of them. I can whip a half dozen Yankees with my pocket knife." Arriving home, McGee instituted daily pistol practice that required Hughes to run over and check the target after each of his master's rounds. "He would sometimes miss the fence entirely, the ball going out into the woods beyond," but when he managed to shoot within the bull's eye's vicinity, he would exclaim, "Ah! I would have got him that time," by which he meant a Yankee soldier. It seemed to Hughes that "there was something very ludicrous in this pistol practice of a man who boasted that he could whip half a dozen Yankees with a jackknife." When Sumter fell, recalled Sam Aleckson of South Carolina, "in the big house there was gladness and rejoicing, while at the quarters there was groaning and lamentation." His fellow slaves "believed that as long as Major Anderson held Fort Sumter, their prospects were at least hopeful; but when Sumter fell, they felt that their hopes were all in vain." "We done now," they kept repeating. But then an old slave named Ben stepped forward to declare that though the white folks could "laugh now," slaves should "wait till by and by." When a young slave eyewitness to Anderson's surrender "drew himself up" and imitated the major declaring to the Rebels that "if I had food for my men, and ammunition, I be damned if I would let you come in those gates!" Ben's wife, Lucy, took heart. "Amen! Bless the Lord!" she cried, and admonished her fellows to "hope and pray." Their master took Aleckson and Uncle Ben to Charleston, where they found whites "going about the streets wearing blue cockades on the lapels of their coats. These were the 'minute men,' and the refrain was frequently heard, 'Blue cockade and rusty gun / We'll make those Yankees run like fun.'" One day young Aleckson overheard recruits saying "they were on their way to the 'Front.'" "Uncle Ben," Aleckson asked, "where's the 'front'?" The old man "made no immediate reply," but eventually looked up at young Aleckson with a scowl. "The front is the Devil," he said, and returned to his chores. 1 "Before TheirTime" Harbingers oofWar * John Brown * Masters' Panic Abraham Lincoln Now everything was stirred up for a long spell before the war to free us come on," said TTTTTemple Wilson. For well over a decade, the nation had been roiling over the slavery issue. Though the Compromise of 1850 had reinforced the Fugitive Slave Act, which required Northerners to assist in returning escaped slaves to their masters, and despite various Northern states' efforts to exclude them, thousands of escaped slaves continued to seek refuge above the Mason-Dixon Line. In 1854, the Republican Party was founded to campaign against the extension of slavery into free territories. Congress passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which held that the settlers living in the two territories could determine for themselves whether they would join the Union as free or slave states. The result was a savage war between proslavery and abolitionist émigrés that would result in hundreds of deaths. A year later, several Northern states enacted laws forbidding state officials to enforce the Fugitive Slave Act. In 1856, as slaves in seven Southern states revolted against their masters, abolitionist Charles Sumner of Massachusetts was almost caned to death for denouncing slavery on the floor of the Senate. The following year, the Supreme Court ruled that an escaped slave named Dred Scott remained his master's property and therefore could not sue for citizenship in the North. And all the while there had been the rising, accelerating drumbeat of Northern abolitionists on the one side and Southern apostles of disunion on the other. As their masters waxed hysterical about Yankee agitation, many of their slaves sought prophecy in signs and omens. "It was talked and threatened and all kinds of bad signs pointed to war," said Temple Wilson, "till at last they just knowed it was bound to come on." "I saw the elements all red as blood," recalled Frank Patterson, "and I saw after that a great comet; and they said there was gonna be a war." Harriet Gresham of Florida recalled that "there were hordes of ants, and everyone said this was an omen of war." "One night before the war come," Dora Jackson's mother "and some other women was washing clothes down at a creek, when all at once they look up at the sky, and they see guns and swords" streak across the firmament and stack themselves together. "They was so scared they run to the house and call old Master and tell him about it. He laughed at them and told them they was just imagining things, but it was just a few days before the war come, and they saw them guns just like they did in the sky." In the winter of 1860 to 1861, Mississippi experienced the worst freeze "that us had ever had," recalled Liza Strickland. "The limbs of the trees got so heavy with ice till they broke off. It sounded like guns firing." Strickland knew "right then and there that was a bad sign, and a war was sure coming, and when it did break out us weren't surprised at all, and us had to stay scared to death for four long years." Before the war "I seen troubles in this land," declared Lu Perkins of Texas. "I seen a big black wave of hating going on over the land and the folks getting poorer and poorer and starving for the childrens and the old." Perkins had a vision of "new kinds of soldiers and folks fighting till blood run over the land," starting in the "far corner of the world and spread over the country" -- the judgment, she said, "for folks being mean and greedy." One night she awoke and saw a "blazing star dragging its long tail along the ground," whereupon a white man ran out into the night crying, "Judgment! Judgment is on us!" In the east the first concrete sign that something momentous was at hand came in the fall of 1859 when a shard from the war for Kansas arced eastward. After leading murderous raids on proslavery encampments along the Missouri border, the abolitionist John Brown and a party of whites and freed blacks set out to spark a servile insurrection by attacking the Federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. Jared Maurice Arter's master had departed for work as the arsenal's inspector of arms when Arter heard that Brown and a party of freedmen had galloped "through the county on the previous night, taken into custody a number of the leading citizens, captured Harpers Ferry and the arsenal, and barricaded himself and his men in the engine-house," where they were "holding the captured citizens as prisoners." Arter recalled that "all the day long, groups of men on horseback, armed with revolvers, shot guns, and rifles, could be seen going towards Harpers Ferry, the scene of excitement." But these vigilantes "accomplished nothing," and it would take Colonel Robert E. Lee and a squadron of marines to dislodge Brown and his comrades. Lee's young slave Jim Parke recalled sitting on his master's broad veranda at Arlington when a soldier rode up. "Been driving his horse hard," Parke recalled. "The Colonel come to the door, and took some papers, and read them. He look right solemn-like." Parke's sister overheard Lee telling his wife to "spread the word among the servants" that he "had to go catch John Brown and all his men." "The soldiers marched right in front of our house," recalled Frank Smith of Virginia, "right by the front gate, when they was going to Harpers Ferry to kill Old John Brown." Two days after his raid commenced, Brown was captured and eventually condemned to death. According to Hillary Watson, Brown declared that though "you Southern people can hang me," the cause he was dying for was "going to win, and there'll soon be a man here for every strand I've got on my head, fighting to free the slaves." "The excitement ran so high and fear was so great" that Brown's Northern supporters "might attempt to rescue him, that few persons except strong men were permitted to witness the execution." But nine-year-old Arter "stood beside my mother, holding to her apron, and saw hanged four of Brown's men" in a scene Arter remembered as "very war-like." John Brown's failure fortified many slaves' belief that only God, not man, could free them, and in His own good time. Pharaoh Chesney concluded that Brown's "fanaticism" made him "a victim to an ill-timed movement," and that abolition "suffered more from such abortive steps than from the combined arguments of the pro-slavery men." Frank Smith believed simply that Brown "was killing white folks" and freeing slaves "before their time." "What God says has got to come, comes," said Jerry Eubanks of Mississippi. "This is written in the Bible." White people might regard Emancipation as the work of man, "but colored people looks cross years at everything. God did it all." "According to what was issued out in the Bible," Charlie Aarons testified, "there was a time for slavery, people had to be punished for their sin, and then there was a time for it not to be." "It was impossible to keep the news of John Brown's attack on Harpers Ferry from spreading," recalled George Albright of Mississippi. A literate slave named Sam Hall remembered the thrill of fear that passed through his master's community in North Carolina. "It was suspicioned by the whites" that their slaves "planned to organize an uprising" and had chosen Hall to command them; and Hall did not know "at what moment I might be led out by the whites and hanged." The attack on Harpers Ferry "threw a scare into the slave owners," Albright remembered. "One day not long after the arrest of Brown, a boy in a nearby orchard shot off a pop gun, and my mistress ran in terror to the house, screaming that the insurrectionists were coming." As their fathers had done after Nat Turner's abortive slave rebellion thirty years before, masters cracked down on their slaves in John Brown's wake. Suddenly they enforced to the letter longstanding but hitherto loosely observed laws against black assemblies, literacy, gun ownership, and alcohol consumption. "Some of the slaveholders would double the proportion of work," recalledWilliam Henry Towns. "They just whipped the slaves so much to keep them cowed down, and cause they might have fought for freedom much sooner." A slave from Paris, Tennessee, said that as a young boy he did not realize he was a slave until just before the war, when local whites "cut Darkies' heads off in a riot" and "put their faces up like a sign board." Brown's raid may have failed to spark a slave uprising, but in the fall of 1860 many Southern whites regarded the election of "Black Republican" Abraham Lincoln as an even graver threat to slavery. "I think it has come to a pretty pass, that old Lincoln," Mattie Jackson's mistress harrumphed, "with his long legs, an old rail splitter" intended to put black people "on an equality with the whites." Before she would see her children on such a footing, she said, "she had rather see them dead." In their recollections, a number of former slaves would claim to have laid eyes on Lincoln before the war. Some may well have encountered not the Abraham Lincoln but his cousin and contemporary of the same name, or perhaps an English immigrant named William Ellaby Lincoln, a somewhat unbalanced Oberlin College theological student who roamed the South before the CivilWar, preaching against the sins of slavery. But it was not the flesh-and-blood Lincoln former slaves conjured so much as a furtive abolitionist phantom swirling through Dixie, stirring up slaves and masters. Not long before the war began, Margret Hulm answered her master's door, and "there stood a big man with a gray blanket around him for a cape. He had a string tied around his neck to hold it on. A part of it was turned down over the string like a ghost cape. He had on jeans pants and big mud boots and a big black hat: kind of like men wear now. He stayed all night. We treated him nice like we did everybody when they come to our house. We heard after he was gone that he was Abraham Lincoln, and he was a spy." "Lincoln came to North Carolina and ate breakfast with my master," recalled Frank Patterson. As he pitched into his "ham with cream gravy made out of sweet milk," biscuits, poached eggs on toast, "coffee and tea, and grits," a presumably sated Lincoln nevertheless warned his host that if whites descended to "conceiving children by slaves" and then buying and selling their "own blood," it would "have to be stopped." "I knowed the time when Abraham Lincoln come to the plantation," Alice Douglass insisted. "He come through there on the train and stopped overnight once." Some slaves "shined his shoes, some cooked for him, and I waited on the table; I can't forget that. We had chicken hash and batter cakes and dried venison that day. You be sure we knowed he was our friend, and we catched what he had to say." She would "never forget so long as I live" his parting words to her master: "If you free the people, I'll bring you back into the Union." But if "you don't free your slaves," he said, "I'll whip you back into the Union." Another story had it that Lincoln had turned against slavery after his wife witnessed the flogging of a pregnant slave in Richmond. "Mrs. Lincoln was horrified at the situation and expressed herself as being so," Irene Coates contended, "saying that she was going to tell the President" as soon as she returned to Washington. Richmond slaves claimed it was this incident that marked "the beginning of the President's activities to end slavery." Sarah Walker depicted Lincoln passing through Saline County, Missouri, "investigating conditions of the slaves." Lincoln's "height and dignity frightened the children, and they fled in hiding" until Walker's father "assured them that Master Lincoln wouldn't harm them," and "they left their places of refuge." Lincoln stood "in all dignity and charm," she recollected, "and yet you had the feeling he was saying all the time, 'I am no better than you are.'" "My mother used to say that Lincoln went through the South as a beggar and found out everything. When he got back, he told the North how slavery was ruining the nation." "I believe I see'd that man once," said Henry Gibbs of Mississippi. Lincoln "come to Marse David's house, pretending to be crippled. Marse David had me show him the way off the place. When we was out of sight, that man put them crutches across his shoulder. I always have believed that man was Lincoln." J. T. Tims of Arkansas was told that "Abe Lincoln come down in this part of the country" with "his little grip" in his hand and asked a farmer for work. "Wait till I go to dinner," the farmer replied. "Didn't say, 'Come to dinner,'" said Tims, "and didn't say nothing about, 'Have dinner.' Just said, 'Wait till I go eat my dinner,'" as he might any poor white who came knocking at his door. For this discourtesy, Tims concluded, Lincoln would plunge the South into war. Excerpted from The Slaves' War: The Civil War in the Words of Former Slaves by Andrew Ward All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.