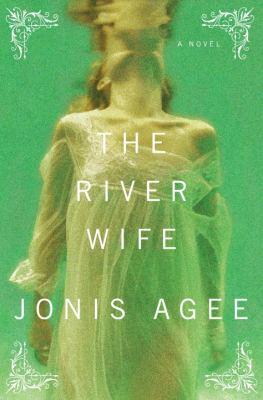

The river wife : a novel

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Stamford | Checked out |

Browse Related Items

| Subject |

| Women > Missouri > Fiction. |

| Genre |

| Domestic fiction. Fiction. |

- ISBN: 1400065968

- ISBN: 9781400065967

- Physical Description 393 pages

- Publisher New York : Random House, [2007]

- Copyright ©2007

Content descriptions

| Immediate Source of Acquisition Note: | LSC 32.00 |

Additional Information

The River Wife

Click an element below to view details:

Excerpt

The River Wife

Chapter 1 HER NARROW IRON BED, WITH ITS LOVELY WHITE SCROLLWORK--A LUXURY      somehow accorded a girl of sixteen though her father was against it from    the beginning--slid back and forth behind the partition as if they were on the river, the roar so loud it was like a thousand beasts from the apocalypse set loose upon the land, just as her father had predicted. Then the partition hastily erected for her privacy crashed to the floor. The cabin walls shook so, her bed heaving like a boat on rough waters. The stone chimney toppled, narrowly missing her brothers, who had leapt awake at the first rumbling and run outside in their nightshirts. "Mother!" she cried, for hers was the last face the girl wished to see on this earth if this were truly Judgment. "Mother!" knowing she was too old to be held like a babe at breast, but wanting it anyway, "Mother!" and the ancient oaks to the south of the cabin groaned and began to crash with mighty concussion and the horses and cows bellowed. She clung to the tiny boat of her bed, and therein lay her mistake. "Mother!" But her mother was busy with the young ones, rushing them in their bedclothes outside the cabin to join her father and brothers, who were on their knees praying while the ancient cypress shook like an angry god overhead, and the birds swarmed in screaming flocks, and the ground opened up. She could smell it, the cabin floor a fissure that stank of boiling sand and muck. There was a terrific hammering and squealing as nails popped from wood, planks pulled apart, and the roof split in two. "Oh my mighty Lord," she prayed, "take me to your bosom where I shall not want." Just then, as if in response, there was a deep rumbling, followed by a loud grating overhead as the roof beam pulled away from the walls with a sudden sigh and crashed down across her legs, numbing them with the sudden unbearable weight and pinning her to her grave. She tried pushing at the beam, but it was too thick and heavy. Still she pushed and clawed, tearing her nails bloody, hammered with her fists, tried to lift her legs and kick out, but they were helpless, unable to move at all against the weight that kept pushing her down, past the point where she could stand it. She screamed until she was hoarse, unable to make herself heard over the chaos. When the shaking subsided, her father appeared in the doorway holding a lantern, her brothers standing just behind, looking so frightened she almost felt sorry for them. "Annie? Annie Lark?" he called into the darkness full of dust and soot from the collapsed chimney. The ground shivered and she could hear her brothers pushing away. "She's dead!" the older brother cried. "Leave her--" They never could abide each other, and now he would consign her to hell. "I'm in here," she called. "The roof beam has trapped me." She was certain that her father would rescue her then. "Here--" Something flew through the air and thudded on the floor beside her. Although she stretched her arm, she could not possibly reach it, and the movement cost her a terrible tearing pain across her thighs. "Father!" she called as another shiver brought another section of roof crashing down halfway to the door. "Pray for strength, dear Annie, read the Scripture in the Bible and pray. He will deliver you!" Her father's voice began to grow distant as he backed away from the collapsing cabin. She called out again, "Help me! Mother, please!" The cabin groaned in a chorus with the falling trees and screaming birds. Then her father drew close again to the cabin door. "I can't dislodge the beam, Annie, there's no time. Your brothers, the horses, nothing will come near to help. Please let us go." His voice was no longer deep and confident, full of authority. It had taken on the pleading softness of her younger brother, a child full of fear and want. The beam was some two feet thick and twenty feet long, its displacement impossible to calculate amid the frantic animals and crying children and their own fearful hearts. She wondered that they did not shoot her like a cow or horse with a broken leg. The roof groaned, spilling dust that appeared to be filled with the brittle leavings of tiny broken stars in the sudden moonlight. "Give me a betty lamp and candle," she said. "And blankets, I'm so cold." She did not mention the pain radiating its terrible burning rays down her legs and up her back. It took her father a moment to collect his courage to enter the cabin, find and light the lamp, and gather several candles and sulphurs. He placed only a single deerskin over her feet, which had begun to turn icy in the weight of the cold. He must take the other blankets to the family, she understood. When he tugged her own quilts up to her chin and kissed her forehead, his body was quaking. "Farewell, dear girl"--his voice grew raspy--"we shall meet on the far shore, clothed in His bright joy." The roof groaned again. His eyes went wild and he took a step back, almost stumbling over the log across her legs, and having to balance himself on the beam, pressing down, which caused a surge of pain that made her cry out. He whirled away and grabbed up guns, powder, and what provisions he could before running out the door into the darkness. She had so much to say that she clamped her lips closed, sealed them from cursing him forever as he hurried away. That was the last she ever saw of her family. The pain came in waves rising up from her legs, clenching her stomach, spreading through her arms and bursting into her head. She panted and cried out in a rhythm as if giving birth, alone, to this terrible night. There was a small window in the wall to her right, and as she lay there waiting for the Beasts of the Apocalypse to devour her, the waters of the damned to swirl about and swallow her, the mighty breath of God Himself to blow her into pieces that would never see salvation, she saw the distant fires devouring houses, heard the unnatural roar and rush as trees along the riverbank collapsed taking great chunks of earth with them, felt the wet hot air escaping from hell itself as the seams of the earth split and the damned cried forth, their breath the foul hissing steam that invaded the world. At first she prayed in between the spasms of pain, but it was a dry excuse. Then she pushed at the beam, tried to dig her fingers into the shuck mattress, hollow a hole to drop through, but to no avail. She tried turning on her side, no, tried dragging herself upwards, no, tried edging out at an angle, no, tried pushing herself down beneath it, out the foot of the bed, no. She was panting and cold in her sweat-soaked gown, longing for a sip of water, which she had forgotten to ask for. We are always more interested in light than anything else, she discovered that night. If we could only see our predicament, then it would be somehow possible to imagine escaping it. In the darkness nothing is possible except terrible occurrences, so she lit the betty lamp. Then in spite of her thirst, she had to relieve herself. Ashamed, she afforded herself the small pleasure despite the hours it meant afterward, lying in the wet. It was hers, not a younger brother's or sister's, and that made a difference. Oh, she was paying for the pride of this bed, she thought, and watched the dawn arrive, first gray coated, then blue and bright through the small window. She fell into a fitful half sleep. So ended the first day. When she awoke, the sun was shining, and she could see for certain the devastation and solitude that was her world. Her legs were merely a heavy aching numbness now. The betty lamp had died, and she wondered that her father could not spare the oil to give comfort to a dying daughter. Looking around the cabin, though, she knew with certainty that they would never return. With the partition down, there was one large room, and she could see the fireplace near the doorway. When the chimney tumbled, some of the large stones had fallen onto the hearth, where her brothers slept in cold weather. In summer, they slept outside on the porch, wrapped in hot blankets against the insects. The large black stew pot had tumbled into the room. A wonder her father had not bothered to pick it up. Her mother would miss the pot, which had served faithfully every day of their lives. Along the wall to her left, the pallet where her younger sisters slept, next to her parents' bed, was strewn with broken crockery and jars of pears her mother had preserved from the first crop of their new trees. How the children loved those pears, so sweet when ripe that the juice ran between their fingers! Her mother must have hastily snatched the few pieces of clothing they owned, for there was nothing of value that she could see. Her father had indeed taken all the blankets. The crock of oil she so desperately needed was broken and spilled across the dirt floor. She was lucky the shaking occurred in the night when no candles or lamps were burning, and the fire in the hearth had so burned down that it was gray empty ash now. The crude wooden rocking horse she had constructed for the baby was on its side but intact beside her parents' bed. He'd never know how his sister had loved him. In the middle of the room, the rough oak table her father had made was crushed by the other end of the beam that imprisoned her legs. The benches too were crushed. Only her mother's rocking chair remained in the corner of the room, miraculously unscathed, its black lacquer finish glowing dully in the dusky light. She had rocked all her babes in that chair, but the carved lion faces with their jaws agape and fierce, enraged eyes had always frightened the girl enough that she never envied the other children given permission to sit in it. Now she imagined the eyes glaring at her, triumphant, and she couldn't even look in that dark corner by the door that hung half off its leather hinges. The hellish smell in the air was gone, replaced by what she surmised to be the dense odor of earth released when the huge trees with the deepest roots were upturned like twigs. It was oddly comforting, the scent of fresh split wood, the dense musk of dirt overriding the sharp stink of piss and the salt rime of her fear. She thought of all the days when she had wanted only to lie abed, dreaming, and now she was cursed to die here, in a growing thirst, her tongue swelling, her throat so parched she had difficulty swallowing. This would be a slow death. Her father was right, she must have been the worst of sinners. What good came of a life such as hers? She tried to make amends in prayer. She begged for release. She promised herself to God. She would be handmaiden pure, and rejoice only in His glory. But nothing worked. And so she began to curse, trying to thrash, to move herself, to tear her legs from under the crushing weight of the beam. Yes, now she could feel it: The numbness was turning again to unbearable pain as her legs began to die. She screamed, hoping some passerby would hear, come to her rescue, but only the wind replied, rattling the broken world, sifting a few snowflakes from the roof. She held her mouth open trying to collect enough to satiate her thirst, but they disappeared on her tongue too quickly. It was well after noon that second day when she heard a knocking at the front of the cabin, and a voice she recognized called her name. It was Matthieu, a boy she had once danced and flirted with at a social, whose family lived in the town of New Madrid. "I'm here!" she cried. "In here--" He came hesitantly, like a deer picking its way into a meadow, stopping every few steps to look for danger. He was a tall, thin boy, with white blond hair and a narrow face that made him look sensitive--sympathetic watery blue eyes, thin nose, and a rather full wide mouth that would be more appealing on a girl perhaps, though she had liked it enough to let him kiss her quickly on the lips. He had tasted of anise. Stopping a few feet away as if to maintain propriety--she was, after all, a girl in a bed--he snatched off his red knit hat and tucked his hands under his arms and inquired as to her health. He didn't look so well either, with dark sleepless circles under his blue eyes, scrapes on both cheeks, blood matting his hair, and coat torn and stuck with burs and dried grass. Still she felt ashamed of the damp she was lying in, the acrid smell, and the full brown head of hair that had been her pride, now tangled like a madwoman's around her face. She could not drive him off, she told herself, she must charm and cajole him, convince him to help her. "Matthieu," she said. "Can you move this log, please?" She was proud of herself, so polite and ladylike. If he came any closer she'd snatch his face and bloody it raw with her nails. Hurry! For God's sake, hurry! she wanted to scream. There had been five big shakes and twenty small ones since last night. She'd been counting. She could hear the river sucking close by. Soon the outer walls would come down. He frowned and looked around the cabin in wonder, his mouth opening and closing in questions that answered themselves. He frowned some more when he glanced up at the open roof, the sagging shingles and boards. "Where is the river now?" she asked. He clambered over the beam, pushing down with his hand inadvertently as his leg caught. She could have killed him, but bit her lip against the painful surge, and smiled as her crushed legs throbbed anew. Her lips were chapped raw and bloody, a fitting color for seduction. "I'm thirsty," she said, her voice croaking at the end. He looked up startled and glanced out the door. She hadn't meant to send him away. "No," she said, "don't leave me." "I'll have to check the well," he said. "It might have been split open, but I have my canteen. It's right outside--" Excerpted from The River Wife by Jonis Agee All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.