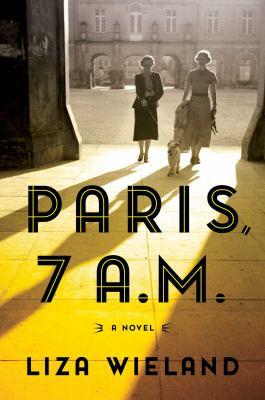

Paris, 7 A.M. : a novel

Imagines what happened to the poet Elizabeth Bishop during three life-changing weeks she spent in Paris amidst the imminent threat of World War II.

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Stamford | Available |

Browse Related Items

- ISBN: 9781501197215

- Physical Description 332 pages ; 24 cm

- Publisher [Place of publication not identified] : [publisher not identified], 2019.

Additional Information

Paris, 7 A. M.

Click an element below to view details:

Excerpt

Paris, 7 A. M.

Paris, 7 A.M. If you can remember a dream and write it down quickly, without translating, you've got the poem. You've got the landscapes and populations: alder and aspen and poplar and birch. A lake, a wood, the sea. Pheasants and reindeer. A moose. A lark, a gull, rainbow trout, mackerel. A horned owl. The silly somnambulist brook babbling all night. An old woman and a child. An old man covered with glittering fish scales. An all-night bus ride over precipitous hills, a heeling sailboat, its mast a slash against the sky, trains tunneling blindly through sycamore and willow, a fire raging in the village, terrible thirst. See? The dreams are poems. And the way to bring on the dreaming is to eat cheese before bed. The worst cheese you can get your hands on, limburger or blue. Cheese with a long, irregular history. This was a crazy notion to bring to college, but you have to bring something, don't you? You have to bring a certain kind of habit, or a story, or, because this is Vassar in 1930, a family name. Some girls bring the story of a mysterious past, a deep wound, a lost love, a dead brother. Other girls bring Rockefeller, Kennedy, Roosevelt. They bring smoking cigarettes and drinking whiskey and promiscuity (there's a kind of habit), which some girls wear like--write it!--a habit. This is a wonderful notion, the nun and the prostitute together at last, as they probably secretly wish they could have been all along. Elizabeth laughs about it privately, nervously, alone in her head. Her roommate, Margaret Miller, has brought a gorgeous alto and a talent for painting. She's brought New York, which she calls The City, as if there were only that one, ever and always. And cigarettes, a bottle of gin stashed at the back of her wardrobe, a silver flask engraved with her mother's initials. Margaret has brought a new idea of horizon, not a vista but an angle, not a river but a tunnel, a park and not a field. She will paint angles and tunnels and parks until (write it!) disaster makes this impossible, and then she will curate exhibitions of paintings and write piercing, gemlike essays about the beauty of madwomen in nineteenth-century art. The cheese, meanwhile, occupies a low bookshelf. Most nights, Elizabeth carves a small slice and eats it with bread brought from the dining hall. And sure enough, the dreams arrive--though that seems the wrong word for dreams, but really it isn't. They arrive like passengers out of the air or off the sea, having crossed a vast expanse of some other element. Elizabeth's father, eighteen years dead. In her dreams, he's driving a large green car. Her mother, at a high window of the state hospital in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, signaling for something Elizabeth can't understand, her expression fierce and threatening. A teacher she loves disappearing into a maze of school corridors. A Dutch bricklayer setting fire to the Reichstag. A two-year-old boy dressed in a brown shirt, a swastika wound round his arm like a bandage. His sister's mouth opened wide to scream something no one will ever hear because she is gassed and then burnt to ashes. All these people trailing poems behind them like too-large overcoats. And Elizabeth is the seamstress: make the coat fit better, close the seams, move the snaps, stitch up the ragged hem. Elizabeth, Margaret says toward the end of October. I'm not sure these are poems. They're more like strange little stories. But I am sure that cheese stinks. I know, Elizabeth says, but it has a noble purpose. Which is what, for heaven's sake? If you want to have peculiar dreams, try this. Margaret holds out the silver flask. Just . . . without a glass? Just. Elizabeth takes a long swallow, coughs. Oh, she says when she can speak. It's like drinking perfume. How would you know that? Margaret says. I quaff the stuff for breakfast, of course! Margaret lies down on her bed, and Elizabeth sits below her, on the floor, her back against the bed frame. So, Margaret begins. About men. Were we talking about men? If we weren't, we should be. I wish I knew some men the way you do, Elizabeth says. And what way is that? To feel comfortable around them. Natural. Maybe I can help. Give you a lesson or two. Start now. Margaret sits up, shifts the pillow behind her back. Elizabeth turns to watch, thinking this will be part of the lesson, how to move one's body, the choreography. Margaret looks like a queen riding on a barge. What poem is that? A pearl garland winds her head: / She leaneth on a velvet bed. Margaret as the Lady of Shalott. When Elizabeth turns back, she sees herself and Margaret in the mirror across the room, leg and leg and arm and arm and so on, halves of heads. Halves of thoughts, too. It seems to do strange things, this drink. It's exhilarating. First, Margaret says, boys--men--they want two things that are contradictory. They want bad and good. They want prostitute and wife. Prostitute and nun, Elizabeth says. Margaret smiles, which makes her entire face seem to glow. Such dark beauty, Elizabeth thinks, like my mother. In some photographs, she looks like someone's powdered her face with ashes. That's the spirit! Margaret says. And not only do you have to know how to be both, you have to know when. Must take some mind reading. Which is really just imagination. Which you have loads of, obviously. Margaret leans forward to rest the flask on Elizabeth's shoulder. This helps, she says. Helps us or them? Both, Margaret says. She watches Elizabeth unscrew the cap on the flask. Not so much this time. Elizabeth takes a tiny sip, a drop. Suddenly, she feels terribly thirsty. A memory crackles out of nowhere, a fire. Much better, she says. Almost tastes good. So it's a math problem, Margaret says. Which do they want, and when. Probability. Gambling. What if you guess wrong? Then you move on. Moving on. That must be the real secret to it. Down the hall, a door opens and music pours out. How have they not heard it before now, the phonograph in Hallie's room? She is trying to learn the Mozart sonata that way, by listening. Miss Pierce tells them it will help, to listen, but it's still no substitute for fingers on the keys, hours alone in the practice room, making the notes crash and break on your own. Margaret is talking about a boy named Jerome, someone she knows from Greenwich, her childhood. Elizabeth gazes up at her, drinks in the calm assurance of Margaret's voice, the confiding tone, the privacy. College can be so awfully public, even places that are supposed to be private: library carrels, bathroom stalls. Jerome was in her cousin's class. Now at college in The City. Columbia. He is bound to have friends. Elizabeth listens to the sounds of the words, the hard-soft-hard c's like a mediocre report card: college, city, Columbia, country. The music of it soothes. She turns to look out the window, rubs her cheek against the nubby pattern of the quilt on Margaret's bed, takes some vague and unexpected comfort in the fabric. A light from the dorm room above theirs illuminates the branches of an oak tree outside, two raised arms, a child asking her mother to be picked up, pressed to a shoulder. She hears a child's voice say the words. Hold me. I'm thirsty. Margaret is talking about men. The tree is asking to be gathered up, held aloft. An impossible request: the roots run too deep, too wide, scrabbling under this dormitory, beyond, halfway across campus. Elizabeth reaches for the flask, takes a longer swallow, then another. Excerpted from Paris, 7 A. M. by Liza Wieland All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.