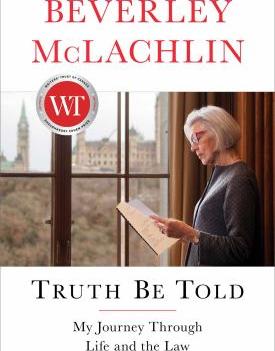

Truth be told : my journey through life and the law

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Stamford | Available |

| Victoria | Available |

| Victoria | Available |

| Victoria | Available |

Browse Related Items

| Subject |

| McLachlin, Beverley, 1943- Canada. Supreme Court. Judges > Canada > Biography. |

| Genre |

| Autobiographies. |

- ISBN: 9781982104962

- Physical Description 373 pages : illustrations (some color) ; 25 cm

- Publisher [Place of publication not identified] : [publisher not identified], 2019.

Content descriptions

| Bibliography, etc. Note: | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Additional Information

Truth Be Told : My Journey Through Life and the Law

Click an element below to view details:

Excerpt

Truth Be Told : My Journey Through Life and the Law

Truth Be Told Prologue IN APRIL 1989, I was sworn in as a justice of the Supreme Court of Canada. Pundits hailed the appointment of a third woman to the court of nine as a remarkable advance for women's rights. I was less convinced. Male justices still outnumbered women by two to one. Most of the speakers at the swearing-in ceremony were men, and when I scanned the courtroom, I saw more male faces than female. As I swore my oath of office in the august chamber of the court, I spared a thought for Emily Murphy, Henrietta Muir Edwards, Nellie McClung, Louise McKinney, and Irene Parlby--the so-called Famous Five. I had long admired and striven to live up to their legacy, and I knew that without them, this moment would not have happened. Would they have been pleased to see a third woman named to the Supreme Court of Canada? I wondered. Yes, I thought. But they would also have been surprised that it took so long. Seventy years had passed since they began fighting for women to be allowed to hold public office. Seventy years. Many years after this momentous day, United States Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg visited our court for the first time. As we sat talking after her tour, Justice Ginsburg fixed me with her dark eyes and, in her customary slow, deliberate manner, asked, "What is the history of women's legal rights in Canada?" I considered a moment before answering. "It started with the Famous Five and the Persons Case." It was 1919 in Edmonton, Alberta, a young community growing into a city. Edmonton was still frontier territory, filling up with people heading west from cities like Montreal and Toronto. Young men seeking wealth and adventure. Young women seeking husbands and sometimes more--an escape from the constraints of the settled East. One of these women was Emily Murphy. The wife of an Anglican minister, mother to four children, and published author, Emily was determined to do whatever she could to help build her new community, and Edmonton urgently needed the rule of law. Emily had no legal experience, but she understood people and what went on in their lives, and she couldn't abide the practice of excluding women from courtrooms when the evidence was, in a (male) judge's view, "not fit for mixed company." She protested and lobbied--arguing that the government had an obligation to create a special court run by women for women--and finally, she secured an appointment as a city magistrate. As she headed to court on her first day, I imagine Emily Murphy was buoyed by the fact that women like her were starting to make their way in the world, just as men did. Earlier that year, Alberta women, after decades of painful struggle, had finally won the right to vote. Headlines proclaimed that women were equal, with full political rights. But if Emily dreamed of a new age of equality, her hopes were soon to be dashed. As the story goes, she entered her little courtroom and the clerk called the case, but no one rose. After a few moments, the lawyer behind the defence table got to his feet. "I apprehend that my friend may have a preliminary motion to put before the court," he said, then sank back into his leather chair. Emily looked inquiringly at counsel for the applicant. "I find myself in a position of some difficulty," the man said. "It seems I am expected to address the court, but I find no court to address." Emily shook her head. She had been duly sworn in the day before, to much hoopla. "Would you be so kind as to explain?" "The matter is one of some delicacy, madam. But let me come to the point: only 'persons' are permitted to occupy positions of public office. Magistrate is a position of public office. A woman is not a 'person' under the law of Canada. You are a woman. Therefore, there is no magistrate in this room, no judge. I cannot proceed." He inclined his head. "If I may be so bold, madam, I suggest you retire so this court may be lawfully constituted before a proper judge." We do not know the precise words spoken or actions taken on that day a century ago. Perhaps Emily was shocked to be told she had no right to sit as a judge--certainly she must have felt angry. What we do know is that she rejected the motion and went on to hear the case before her. In the years that followed, other female magistrates in Alberta were challenged simply because they were women, and eventually the issue made its way to the Supreme Court of Alberta, which ruled that despite their gender, women were "persons" and hence capable of sitting as judges. But the issue festered and rankled. Women could be judges in Alberta, but what about the rest of the country? And what about other public positions? Did women have the right to be members of Parliament or senators? The question would soon be answered. In 1922, Murphy herself was up for an appointment to the Senate. Predictably, the government of Prime Minister Mackenzie King rejected her nomination on the grounds that Murphy was not a "person" capable of holding public office. Between 1917 and 1927, five different governments proposed women for Senate seats. The answer was always the same. So once again, Emily Murphy took action. She invited Edwards, McClung, McKinney, and Parlby to her home. She proposed that the five of them draft a petition to the governor general, seeking a reference to the Supreme Court of Canada concerning the interpretation of the word "persons" in Section 24 of Canada's constitution, the British North America Act. The Famous Five, as they are now known, raised money, hired lawyers, and mounted a case to contest the established view that women were not "persons" and could not hold public office. Prime Minister King's government agreed. The Supreme Court of Canada did not. It was obliged--or felt itself obliged--to apply the law of the British Empire, which was that women were not "qualified" to hold public office. 1 The Famous Five refused to accept defeat. They raised more money and hired a new lawyer to take their case to the final court of appeal--the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in far-off London, England. To the surprise of everyone and the consternation of many, the women succeeded. While newspaper editorials predicted the demise of civilized society, Viscount Sankey, writing for the Judicial Committee, stated that society had changed. More and more, women were occupying positions of public responsibility, he noted, and the time had come to recognize that women were indeed "persons" capable of holding public office. The constitution, he added, had "planted in Canada a living tree capable of growth and expansion within its natural limits." 2 As I shared the story of the Persons Case with Justice Ginsburg and the other judges around the luncheon table, I reflected on how the case had changed Canadian law forever--not just in the rights it accorded women, but also in establishing that Canadian law was not frozen in time, but rather was capable of measured and principled evolution to keep pace with social change. It has been said that Canada came of age as a nation with its contribution to the ultimate victory of England and the Allies in the First World War. It can equally be said that Canada came of age as a legal and jurisprudential force, whose law would be studied and emulated elsewhere, with the Persons Case of 1929. Sixty years after the Persons Case was decided, as I was sworn in as the third woman ever to sit on the Supreme Court of Canada, the path set by those early trailblazers was at the front of my mind. It was a moment of pride, tempered only by the thought of how many women in decades past had been denied the immense privilege of sitting on the country's highest court. What took us so long? I thought. And then, What is still holding us back? Thirty years later, I still ponder these questions. What follows is the story of one "person"--of her journey towards a world in which women and men are truly equal, where people of any gender, race, or background can aspire to the same goals. Excerpted from Truth Be Told by Beverley McLachlin All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.