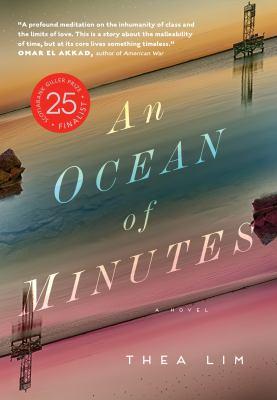

An ocean of minutes : a novel

America is in the grip of a deadly flu pandemic. When Frank catches the virus, his girlfriend Polly will do whatever it takes to save him, even if it means risking everything. She agrees to a radical plan--time travel has been invented in the future to thwart the virus. If she signs up for a one-way trip into the future to work as a bonded labourer, the company will pay for the life-saving treatment Frank needs. Polly promises to meet Frank again in Galveston, Texas, where she will arrive in twelve years. But when Polly is re-routed an extra five years into the future, Frank is nowhere to be found. Alone in a changed and divided America, with no status and no money, Polly must navigate a new life and find a way to locate Frank, to discover if he is alive, and if their love has endured.

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Community Centre | Available |

Other Formats

Browse Related Items

- ISBN: 9780735234918

- Physical Description 322 pages ; 21 cm

- Publisher [Place of publication not identified] : [publisher not identified], 2018.

Additional Information