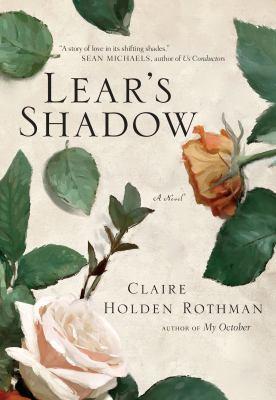

Lear's shadow : a novel

During a sweltering, stormy Montreal summer, Bea Rose finds herself about to turn forty having lost her lover, her business, and her bearings. When the opportunity to work for an outdoor production of King Lear arises, she grabs it despite her utter lack of theatre experience. Things get off to a rocky start when Bea learns the artistic director, Arthur White, is a childhood friend whose presence stirs up painful memories. Then she inadvertently sparks the lascivious attentions of the aging star of the play and alienates the stage director, who happens to be his former wife. As Bea learns the ropes of her new role, her beloved but demanding father begins behaving erratically and losing himself in forgetfulness and her younger sister Cara reveals cracks in the foundation of her apparently perfect life as a devoted mother and co-owner, with her charismatic husband, of a successful raw foods restaurant. The sisters do their best to care for their father, but his deteriorating condition soon exceeds what either can handle. To make matters worse, the star of Lear is also faltering amidst the confusions of age, illness, and regret over transgressions from his past. In a masterful scene of raucous celebration whirling out of control, the various forces in Bea's life collide in a shocking act that could destroy more than one life--or reveal how those lives might come together in new and stronger ways.

Browse Related Items

| Subject |

| Drama > Fiction. Fathers and daughters > Fiction. Canadian fiction. Montréal (Québec) > Fiction. |

| Genre |

| Fiction. |

- ISBN: 9780735234253

- Physical Description 319 pages ; 21 cm

- Publisher [Place of publication not identified] : [publisher not identified], 2018.