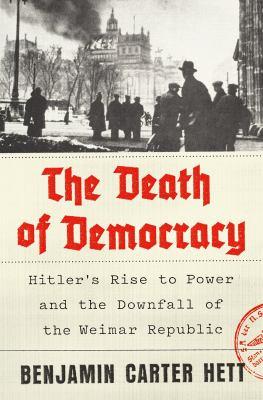

The death of democracy : Hitler's rise to power and the downfall of the Weimar Republic

Hitler promised to fix the economy, to create jobs, and to make Germany great again How did Hitler happen? Germany's Weimar Republic was a state-of-the-art modern democracy, with a proportional electoral system and protection for individual rights and freedoms, expressly including the equality of men and women. Germany had the world's most prominent gay rights movement. It was home to an active feminist movement that, having just won the vote, was moving on to abortion rights. The death penalty had virtually been abolished. And workers had won the right to an eight-hour day with full pay. Jews from Poland and Russia flocked to Germany's greater tolerance and openness. Hitler came to office in January 1933 with the largest number of seats in the Reichstag, Germany's parliament. Like the three chancellors before him, Hitler had been put into office by a small circle of powerful men who sought to take advantage of his demagogic gifts and mass following to advance their own agenda. They assumed they had Hitler squarely under control. Hett's book is a short history of how Adolf Hitler, once elected, used the levers of power to destroy the Weimar democracy and replace it with a Nazi dictatorship. The parallels to current politics are clear and disturbing. Hett examines the political and social context in which the Nazis rose to power and how Hitler himself was a shrewd and intuitive political player. Hett writes with the drama, detail, and pacing that makes his account read like a compelling political thriller.

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Victoria | Available |

Browse Related Items

- ISBN: 9780735234819

- Physical Description xix, 280 pages ; 25 cm

- Publisher [Place of publication not identified] : [publisher not identified], 2018.

Content descriptions

| Bibliography, etc. Note: | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Additional Information