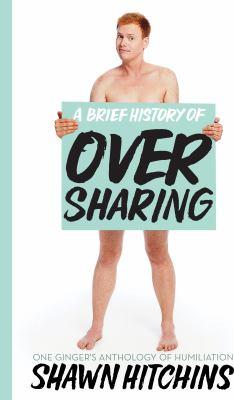

A brief history of oversharing : one ginger's anthology of humiliation

Comedian Shawn Hitchins explores his irreverent nature in this debut collection of essays. Hitchins doesn't shy away from his failures or celebrate his mild successes--he sacrifices them for an audience's amusement. He roasts his younger self, the effeminate ginger-haired kid with a competitive streak. The ups and downs of being a sperm donor to a lesbian couple. Then the fiery redhead professes his love for actress Shelley Long, declares his hatred of musical theatre, and recounts a summer spent in Provincetown working as a drag queen. Nothing is sacred. His first major break-up, how his mother plotted the murder of the family cat, his difficult relationship with his father, becoming an unintentional spokesperson for all redheads, and many more. Blunt, awkward, emotional, ribald, this anthology of humiliation culminates in a greater understanding of love, work, and family. Like the final scene in a Murder She Wrote episode, A Brief History of Oversharing promises everyone the A-ha! moment Oprah tells us to experience. Paired with bourbon, Scottish wool, and Humpty Dumpty Party Mix, this journey is best read through a lens of schadenfreude.

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Victoria | Available |

Other Formats

Browse Related Items

| Subject |

| Hitchins, Shawn. Comedians > Canada > Biography. Entertainers > Canada > Biography. |

| Genre |

| Biographies. Autobiographies. |

- ISBN: 9781770413269

- Physical Description 213 pages ; 21 cm

- Publisher Toronto : ECW Press, [2017]

- Copyright ©2017

Additional Information