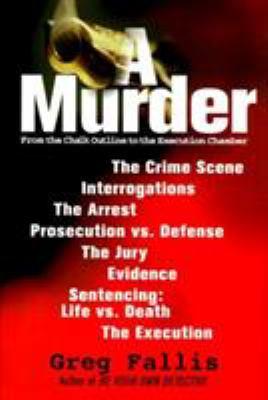

A murder : from the chalk outline to the execution chamber

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Community Centre | Available |

Browse Related Items

- ISBN: 0871318881

- Physical Description 256 pages : illustrations

- Publisher New York : M. Evans and Co., [1999]

- Copyright ©1999

Content descriptions

| Immediate Source of Acquisition Note: | LSC $29.95 |

Additional Information

A Murder : From the Chalk Outline to the Execution Chamber

Click an element below to view details:

Excerpt

A Murder : From the Chalk Outline to the Execution Chamber

Chapter One A MOST ORDINARY MURDER He hadn't meant to kill her. Not really. It just sort of turned out that way.    They'd met as planned early that morning at a diner near his apartment. Over breakfast they'd discussed the photo shoot--the financial arrangements as well as what he expected from her during the shoot. He'd had her sign a model's release form for the photos and another stating she was of legal age. He'd also explained again that he was shooting the film on spec, that neither of them would see a dime from the photographs unless a magazine bought them. He would donate his time, his expertise, and his film; she would donate her time and her body. Together they might be able to make a few bucks.    Not that money was his main interest in shooting the photos.    He hadn't expected much to come from the shoot. After all, the woman wasn't really model material. It wasn't that she was homely; a lot of models had faces that weren't traditionally pretty. It was just that she had dozens of small flaws and imperfections. Her teeth were uneven, her skin was spotty, she was perhaps fifteen or twenty pounds too heavy, her nose was a bit too wide. Worst of all, she had a tattoo on her shoulder. It was a quality tattoo--not one of those cheesy reform school jobs. But it wasn't a very feminine tattoo, he thought. Some sort of snake. He thought it made her look cheap.    Still, some of that could be dealt with in the darkroom. He thought he might be able to sell a few nude shots to one of the lower-rung biker magazines. She had something of that "biker chick" look--a little cheap, a little sleazy, a little hard. That was why he'd picked her.    After breakfast they drove his small camper to Marshtown Park just south of town. The park was empty, as he'd known it would be. It was rarely used during the week. In fact, it was rarely used on weekends before noon. It was a perfect spot for an outdoor location and he'd used it several times before.    The light had been excellent. They'd spent nearly ninety minutes shooting photographs. He went through three rolls of film. Everything had gone surprisingly well, considering the woman wasn't a professional model. She listened and paid attention, she followed directions, she was enthusiastic and didn't complain. He'd known pros who weren't that good. It was a shame her body had so many flaws.    Three times during the shoot she'd used the camper to change clothes. He'd converted the little recreational vehicle into a traveling photography studio. It was perfect for location shoots: There was plenty of room for his equipment, it had a kitchen, and the tiny bathroom doubled as a dressing room. And it had a bed.    The shoot ended around noon. While she changed clothes in the bathroom he'd made sandwiches and mixed a couple of drinks. Seabreezes. Vodka, orange juice, cranberry juice.    In hers he'd dropped a tablet of Rohypnol.    Rohypnol. On the street, folks called called the drug "roofies" or "rope." The media called it the "date rape drug." For once the media got it right. He could pick up roofies for three bucks a tab. A remarkable price for a wonder drug. It dissolved easily in alcohol; it was colorless, odorless, and tasteless; it acted as a sedative; and--best of all--it caused short-term amnesia.    He'd been using roofies on models for nearly a year now. One drink, one roofie ... and half an hour later they were out cold. Then he could do whatever he wanted with them. !t had always worked perfectly before. He'd always been careful to clean them up when he was done. They'd wake up six hours or so later, confused and embarrassed, uncertain about what had happened. But none had ever complained. Some had even apologized for passing out on him. It was the stress, he always told them. It was a sign of artistic temperament. They liked that.    It wasn't as if he had to use roofies to get laid, he told himself. He'd done well enough before he discovered them. A lot of amateur models would do almost anything if they thought it might help get their photos published. The truth was he rather enjoyed the effect roofies had on women. He liked the feeling it gave him. The feeling of power. Control.    But this time something had gone wrong. Maybe he'd been sold a bad batch. Not that it mattered. All that mattered was this time the woman didn't stay drugged. She'd started to wake up while he was ... in her. And she'd begun to struggle. She hadn't been alert enough to put up much of a struggle, but still he'd panicked.    They'd been on the narrow bunk of the motor home and he'd acted on instinct. He'd grabbed her by the throat. Not to kill her ... just to keep her from shouting. But she kept struggling and kept moving her body and he'd become even more aroused. And, when he was finished ... well, there she was. Dead.    Still, he hadn't meant for her to die. He hadn't even meant to hurt her. Not really. It was all just an accident.    Would that matter to the police? he asked himself. No, the police would look in the back of his camper and all they'd see was a dead, drugged woman with his semen leaking out of her. His life was about to be ruined ... and for what? For a cheap biker slut he'd first met in a bar? For a woman who almost certainly would have slept with him--or anybody else--to get her photograph in even a cut-rate skin mag? For somebody no one would ever miss?    No, it wasn't fair. There had to be some way out of it. MURDER--A CRIME OF INFINITE VARIETY The terms murder and homicide are often used interchangeably. However, they actually have slightly different meanings. Homicide refers to the act of one person killing another; murder refers to an unlawful homicide.    There are a number of situations in which people lawfully kill others. Soldiers in combat, law enforcement officers in the prevention of a violent crime, executioners of a criminal convicted of a capital crime--these are acts of homicide, but not acts of murder. The result, of course, is the same--a person killed lawfully is just as dead as one killed unlawfully. However, a lawful killing is a regulated killing. Soldiers in combat, for example, must follow specified rules of engagement and the Geneva conventions. Law enforcement officers must abide by departmental policies and state laws regarding the use of lethal force. Execution teams follow a strict protocol. None of these people have a "license to kill."    The focus of this book is murder --the unlawful killing of another person. There are two primary ways to approach the concept of murder: from a legal perspective and from a criminological perspective. The legal perspective is the approach taken by those who make, enforce, and interpret the law. The criminological perspective is the bailiwick of scholars and students of behavioral and social trends.    Consider two different murders: A postal worker goes to work one morning and shoots three of his co-workers to death. A drug dealer shoots another drug dealer at an inner city street corner over a turf dispute. The legal approaches to these two very different crimes will differ radically from the criminological approaches.    The legal approach focuses on the act itself. Why did the postal worker shoot his co-workers? Was he targeting specific people, or shooting at random? Was he rational at the time of the crime or was he suffering from a psychiatric disorder? Was he under the influence of a mind-altering substance? The criminological approach, on the other hand, concentrates on the trend toward acts of violence among postal workers. Is there something about the social environment of post offices that contributes to acts of violence? What are the similarities and differences between the acts of post office violence? Are workers in certain employment positions--mail sorter, route carrier, drivers--more likely to engage in violence? Are there any similarities in the victims?    In the drug dealer murder the legal approach focuses on the ability to prove the case against the shooter. Are there witnesses? If so, can they identify the shooter? Are they willing to testify? Do the recovered bullets match the weapon found on the suspect? The criminologist, on the other hand, examines the crime with an eye toward learning about the culture of drug dealing. How is turf determined? What are other ways of settling turf disputes? Are there differences and similarities between a turf murder in Detroit and one in Boston or Des Moines?    Both legal and criminological perspectives are important; each offers a unique and valuable understanding of murder. Legal Perspectives of Murder This is the purview of lawyers, legislators, and police officers. The law is concerned with responsibility for actions. The questions asked by lawyers, legislators, and police officers deal with individual culpability. Who is responsible for a particular act? How do we hold people accountable for their behavior? How do we balance the search for justice with the rights due to people accused of crimes?    The first and most critical function of the legal perspective is to carefully define the behavior under question. You can't hold a person responsible for committing a crime unless you have clearly spelled out the elements of that crime--even a crime as obvious as murder.    One reason it's so critical to clearly define murder is because not all murders are alike. While all murders are bad, some are worse than others. What makes one murder worse than another? The legal perspective has one answer--the intent of the offender.    Intent matters. We know this intuitively. Even a dog, it has been said, knows the difference between being tripped over and being kicked. The greater the intent, the more serious the crime; the more serious the crime, the more severe the punishment.    In the following legal definitions of murder you'll notice a gradation of intent. The level of the offender's intent, in fact, is the primary distinction between the different categories of murder. Categories of Murder Legally, murder is divided into several categories or degrees. The designations of these categories vary in different jurisdictions; however, we can generally classify murder in the following categories. Murder in the First Degree This is the willful, deliberate, and premeditated killing of another person. This means the murderer wants to kill the victim (willful), intends to kill the victim (deliberate), and plans the crime before carrying it out (premeditated). All three elements are critical, but the primary consideration of first degree murder is premeditation. The length of time the offender plans the crime needn't be very long; the time it takes to walk from the living room into the bedroom to fetch a shotgun is time enough to be considered premeditation. All that is required is a sufficient length of time to demonstrate that an intent and a plan to kill had been established in the offender's mind. This state of mind is referred to as "malice aforethought"    An example of a first degree murder would be a husband who decides to kill his wife for her insurance money. Murder in the Second Degree In most jurisdictions this is the willful killing of another without the element of premeditation. The offender has the intent to kill the victim, but there is no malice aforethought. Generally, second degree murder is a crime of passion. These crimes are often committed in a fit of rage or fear. They tend to be reactive crimes; something happens that sparks the event. The offender acts on the spur of the moment, without really considering the consequences of the act.    An example of a second degree murder would be a woman who kills her boyfriend when she finds him molesting her daughter. She may intend to kill the boyfriend, but she didn't plan the crime in advance. Manslaughter Manslaughter is generally considered a crime of reckless indifference to human life. The offender doesn't intend to kill the victim, but nonetheless deliberately acts in a way he knows to be dangerous and possibly life-threatening.    An example of manslaughter would be two young men on a highway overpass, dropping balloons filled with paint onto cars as they pass beneath them. If a balloon causes a startled driver to crash into the bridge abutment and die, the two would be guilty of manslaughter. They may not have intended to kill the driver, but they knowingly acted in a manner that showed a reckless indifference to the fates of their victims. Negligent Homicide This is a crime in which the victim dies as a result of gross negligence. The offender has no intent to kill the victim, nor does the offender behave recklessly. The death of the victim is due to carelessness or neglect.    An adult who leaves a very young child alone for a weekend would be guilty of negligent homicide if that child accidentally starts a fire and dies of smoke inhalation. The adult didn't intend any harm to come to the child and yet the child is dead. It's the egregious carelessness of the act that makes it criminal. FELONY MURDER Most jurisdictions have a legal category known as "felony murder." This refers to a situation in which a person dies during the commission of a felony. Anybody involved in the commission of the felony is responsible for the death of the victim. It doesn't matter if the offender didn't play a direct role in the death. It doesn't even matter if the offender was aware of the death of the victim--the offender is nonetheless held responsible. For example, Smith and Jones decide to rob a liquor store. Smith waits outside in the getaway vehicle while Jones enters the store. Jones robs the clerk at gunpoint. As he is leaving the store Jones shoots and kills the clerk. It's irrelevant that Smith waited outside. It's irrelevant that Smith may not have carried a weapon, or that he was entirely ignorant that Jones shot the clerk. Under the felony murder rule Smith is equally responsible for the clerk's death. In fact, if the clerk had pulled a gun and killed Jones, Smith could be charged with felony murder in the death of his partner (although the clerk, acting in self-defense, probably would not be charged). Any death resulting from the commission of a felony can invoke the felony murder rule. Not every felony counts, though. Some courts have ruled that the underlying crime "must be inherently or potentially dangerous to human life." If a death should occur during the commission of a forgery, for example, it's unlikely the felony murder rule would apply. Non-criminal Homicide As noted earlier there is a distinction between homicide and murder, the distinction being that murder is an unlawful homicide. We mentioned some of the more obvious forms of lawful homicide---soldiers in combat, police officers in the line of duty, execution teams. These, as we noted, are regulated killings by people authorized to commit them. However, there are also situations in which an ordinary citizen might commit a homicide that is considered either excusable or justified. Excusable Homicide An excusable homicide is, essentially, an accident in which one person kills another. There is no intent to kill, no reckless disregard for the safety of another, no negligence. For example, a subway motorman who runs over and kills a person who had fallen or jumped in front of his moving train has committed an excusable homicide. The motorman did, in fact, kill the victim; nevertheless, the killing may be excused because it was unintentional and unavoidable. Justifiable Homicide There are certain circumstances under which the intentional killing of another person by an ordinary citizen is considered justifiable. These circumstances vary from state to state, but generally include the defense of oneself or the defense of another from imminent danger of death or great bodily harm. In other words, a homicide is considered justified when the killer believes he is protecting himself or another from immediately being killed or badly injured.    Notice that the belief of imminent death or great bodily harm is enough to justify the killing. Several legal rulings have held that the danger need not be real so long as the person reasonably believes the danger exists and is imminent. For example, a clerk in a liquor store might reasonably believe he or she is in danger if a person enters the store with a pistol drawn. The pistol may be unloaded ... or even a realistically crafted squirt gun. All that matters is that any reasonable person under the same circumstances would also perceive the situation as imminently dangerous.    Some states have a wider scope of situations in which a homicide committed by a common citizen may be considered justifiable, including: · the defense of property (generally where the loss of the property would constitute a felony); · the defense of an unauthorized attempt to enter a dwelling place · situations in which a citizen has been commanded or authorized to act by a legitimate law enforcement officer; such as in the course of the retaking of a felon who has escaped, the suppression of a riot, or the lawful preservation of the peace    It should be noted that many states have passed laws specifically excluding the defense of unborn fetuses from the domain of justifiable homicide. Criminological Perspectives of Murder Where the legal perspective is primarily concerned with individual responsibility and intent, criminologists are concerned with the social circumstances and patterns of murder. Lawyers, legislators, and police officers want to know who is responsible for a particular act, the degree to which they are responsible, and the rules under which they are required to prove responsibility. Criminologists want to understand why murders happen and what that says about society and culture.    For that reason criminologists aren't interested in individual crimes so much as how those individual crimes can be categorized into meaningful groups. Rather than ask who killed the bank guard during the robbery of the Bailey Street Bank, criminologists will ask what the Bailey Street Bank robbery has in common with other bank robberies or what the person who committed that particular robbery has in common with other bank robbers.    These radically different questions lead criminologists to categorize murder differently than legalists. The following categories are examples of some of the ways criminologists look at murder. Drug-related Murder We often hear reports of "drug-related" murders on the evening news. The phrase seems to elicit a rather hazy image of young, urban men (usually African-American) killing each other. That image is based in part on fact, in part on fiction, and in part on racism. Drug-related murders aren't as simple as news reports would lead us to believe. They are, in fact, very complex social crimes and include a variety of subcategories. Turf Murders Many drug-related murders are territorial in nature. Drug dealers, like all business operators, tend to stake out a territory, or turf. The territory might be based on geography or on product. A drug dealer may assert control over a specific physical area (a neighborhood, a street corner, a building) or over a specific drug category (such as heroin, cocaine, or crack) within an area. An attempt by another drug dealer to intrude on that territory leads to conflict, which might result in murder. It's nothing personal; just business. Legitimate corporations engage in similar, though usually less lethal, competition. Business Practice Murders Like all business operators drug dealers sometimes suffer as a result of deceitful business practices. They may be sold merchandise that isn't of the quality they'd been led to expect. They may not receive full payment for their merchandise (or not receive payment at all). They may enter into an agreement to launder money, only to discover that the launderer is now demanding a higher exchange rate. As with legitimate business operators, a drug dealer's reputation for consistently delivering a quality product is important. Drug dealers are as careful to preserve their reputations as IBM, General Mills, or Maytag.    Unlike legitimate business operators, however, drug dealers can't bring their business disputes to court. They must resolve these disputes themselves, and they often resolve them through violence. In fact, among drug dealers a reputation for lethality in resolving disputes is good for business. It reduces the odds others will engage in the same practice. Robbery Murders In an odd way drug dealers are attractive targets for very aggressive armed robbers. Drug dealers often carry large sums of cash, they are often holding significant quantities of drugs (which can either be used or resold), and they are unlikely to report a crime to the police.    However, it takes an extremely aggressive armed robber to consider robbing a drug dealer. In addition to carrying drugs and cash, dealers also often carry very powerful firearms. An encounter between an aggressive armed robber and a well-armed drug dealer frequently results in one or more dead bodies.    A less common form of drug-related robbery murder involves an attempt by a drug user to obtain money to buy drugs. Intimidation Murders Since their work is illegal, drug dealers frequently find themselves in conflict with the criminal justice system. One way some drug dealers attempt to avoid imprisonment is by intimidating or silencing potential witnesses against them. Dead men, as they say, tell no tales. * * *    Drug-related murders are often difficult for the police to solve. The people involved--the killer(s) and victim(s)--rarely have any meaningful social connections to each other. They may barely know each other, and that means there are few obvious suspects. The people most likely to have seen the crime take place are rarely eager to help the police, and that means there are few willing witnesses. The venues in which drug-related murders take place--street corners and drug houses--frequently have a great deal of transient traffic, and that means the physical evidence is often confusing. As will be discussed later, it's no coincidence that the increase of drug-related murder corresponds with the decrease of murder clearance rates. Mass Murder Many people confuse mass murder, spree murders, and serial murder. All involve multiple killings but they are nonetheless very distinct modes of murder. The distinction depends largely on the length of time between the killings and, to a lesser extent, the area in which the killings take place. The killings in a mass murder are temporally proximate, meaning the victims are all killed within a short period of time--a few seconds to a few hours. They usually take place within the same general area. Spree killings take place over a slightly longer time frame and involve greater distances, sometimes several different states. The killings in a serial murder, by contrast, take place over a longer period of time--days, months, even years may pass between killings. Like spree killings, serial murders are not confined to one locale. Spree killings and serial murder will be discussed in more detail later.    Mass murder entered and became firmly lodged in the contemporary American consciouness in 1966. On the morning of August 1, a heavily armed twenty-five-year-old man named Charles Whitman made his way to the top of the bell tower on the campus of the University of Texas at Austin. After barricading the door he opened fire on the people below. Whitman killed twelve people that morning (he'd killed his mother and wife the night before) and wounded more than thirty others before being shot and killed himself by a police officer.    Whitman wasn't the first mass murderer in the United States. There are reports of mass murders as early as 1866 (a farmhand named Anton Probst murdered a family of eight with an axe) and it's certain other mass murders took place before then. Nor was Whitman the first to use semi-automatic firearms to systematically kill bystanders (in 1949 a twenty-eight-year-old pharmacy student named Howard Unruh took a walk through East Camden, New Jersey, shooting people he encountered; he killed thirteen people--including two children--in twelve minutes). Whitman, however, was the first mass murderer of the modern era, the disaffected sniper.    Data suggests that some type of mass murder takes place in the United States at least once a month, possibly as often as once a week. Murders with multiple victims are also slowly rising. In 1976 less than 3 percent of all murders had multiple victims; by 1997 that proportion has risen to 4 percent.    We can divide mass murders into two broad categories: public mass killings and private, domestic mass killings. In general, only public mass killings receive national news coverage; private, domestic mass killings are often perceived as community events and usually receive only local news coverage. Public Mass Killings These are the crimes that generally come to mind when we hear the term "mass murder." As the name suggests, public mass killings almost always take place in a very public arena--restaurants, shopping malls, post offices, schoolyards, office buildings, etc. Most of the offenders who commit public mass killings are white males. Although most mass murderers are between the ages of twenty and thirty-five, some have been as young as eleven and as old as sixty-four.    There doesn't appear to be any consensus in regard to the motives of mass murderers. In general they appear to be acting out of frustration and rage, but the spark that ignites a mass killing varies widely from case to case. Quite often the mass murderer attempts to resolve his frustration in other ways--by writing letters to officials or the editorial pages in newspapers. The mass murderer is frequently known by the people in his community as a crank or frightening eccentric.    In some instances, the mass killer will target a specific individual--an ex-wife, a former girlfriend, a representative of an institution. However, others in the vicinity of the targeted victim are also killed. For example, the most deadly non-political mass murder in recent history took place in the Bronx, New York, in 1990. Julio Gonzalez, angry with a former girlfriend, set fire to the social club in which she worked. Eighty-seven people died in the resulting blaze.    In other cases the victims are simply selected at random. In July of 1981, for example, an unemployed security guard named James Huberty entered a McDonald's restaurant in San Ysidro, California, and opened fire on the staff and customers. He killed twenty-one and wounded more than twenty others.    Some public mass killings seem to be spontaneous outbursts sparked by an incident that seems trivial. For example, in August of 1982, a fifty-one-year-old Miami man named Carl Brown became unhappy with the repair work done on his lawn mower. He rode his bicycle to the repair shop, where he shot and killed eight men and women. Other mass killings appear to be well thought out and meticulously planned. When Charles Whitman climbed to the observation platform of the clock tower at U.T. Austin, he went prepared for a long siege. He brought along a footlocker containing food, toilet paper, extra weapons, and spare ammunition.    Mass murderers tend not to be concerned about being arrested for their crimes. These crimes are usually meant to be final acts. A large number of mass murderers are killed by the police or commit suicide at the end of their rampage. A smaller number surrender peacefully to law enforcement officers when they have finished their killing. It appears the more planning a mass murderer puts into his crime the less likely he is to survive the event.    As shown in the examples mentioned, the two weapons of choice for most modern mass murderers are semiautomatic weapons and fire. The large magazines available for semiautomatic pistols and rifles allow the offender to fire a great many high-powered bullets without having to pause to reload. This makes them ideal tools of mass murder. Fire is even more lethal. Arson is a comparatively inexpensive crime and requires less skill than shooting. Private, Domestic Mass Killings Although these crimes receive less attention, they are the most common type of mass killing. These are mass murders in which one family member kills some or all of the other family members.    We have much less data on these offenders than on the more traditional mass murderers. Researchers have only recently begun to regard domestic mass killings as a form of mass murder.    These crimes are almost always committed by a man--the father, stepfather, husband, live-in boyfriend, or a former husband or live-in boyfriend. The killings are usually preceded by a turbulent relationship marked by violence and jealousy.    By and large, domestic mass killings result in a lower body count. One reason this is so is because there are simply fewer targets in a home than in a public arena. The killing stops when the rage recedes or the killer runs out of family members. These crimes often end with the offender committing or attempting suicide.    Private, domestic mass killings take place with alarming regularity. Even as this chapter was being written, Shon Miller of Gonzales, Louisiana, burst into the New St. John Fellowship Baptist Church during an evening Bible class and murdered his estranged wife and son. Shortly before arriving at the church, Miller had fatally shot his mother-in-law. Miller was later shot and killed by police.    In the two years before the rampage Miller had burned the family's trailer, slashed the tires on his wife's vehicle, and had been arrested and jailed for physically assaulting her. He had also been jailed for violating a restraining order prohibiting him from having contact with her. Juvenile Mass Murder In the recent past we have seen an alarming spate of multiple murders committed by juveniles. Juvenile mass murder appears to be the domain of small town or suburban white boys. Many of these crimes have taken place in a venue normally considered safe--the school.    In October of 1997 a teenager in Pearl, Mississippi, killed two girls (one of whom was his former girlfriend) and wounded seven other students at his high school. The night before, he had stabbed his mother to death. Two months later a high school student in Paducah, Kentucky, opened fire on a group of fellow students gathered to say a prayer in the hallway before class. He killed three and wounded five others. The three dead students were all girls. Three months later, in March of 1998, the small Arkansas town of Jonesboro was horrified when two young boys ambushed their classmates. After triggering a fire alarm the two boys proceeded to shoot the teachers and students as they filed out of school. When they had finished, four students and one teacher were dead. Ten others were wounded. Two months later a recently suspended high school student in Springfield, Oregon, opened fire in the school cafeteria. He killed two and wounded eight before being subdued by fellow students.    What do these juvenile mass murderers have in common? Alienation from their classmates, resentment at real and perceived personal slights, a keen interest in violent media (movies and computer games), and access to firearms. Combined with a teenager's sense of drama and lack of skill in resolving conflict, it's a deadly combination. It's also no coincidence that so many of the killers are boys and so many victims are girls. There is a gender component to these killings that is usually ignored. (Continues...) Copyright © 1999 Greg Fallis. All rights reserved.