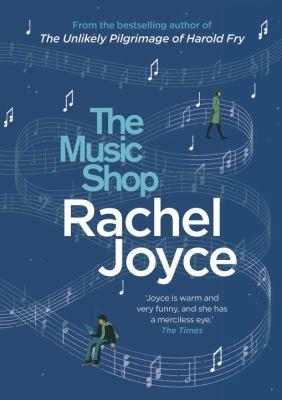

The music shop

It's 1988. The CD has arrived. Sales of the shiny new disks are soaring on high streets in cities across the England. Meanwhile, down a dead-end street, Frank's music shop stands small and brightly lit, jam-packed with records of every kind. It attracts the lonely, the sleepless, the adrift. There is room for everyone. Frank has a gift for finding his customers the music they need. Into this shop arrives Ilse Brauchmann--practical, brave, well-heeled. Frank falls for this curious woman who always dresses in green. But Ilse's reasons for visiting the shop are not what they seem. Frank's passion for Ilse seems as misguided as his determination to save vinyl. How can a man so in tune with other people's needs be so incapable of helping himself? And what will it take to show he loves her? The Music Shop is a story about good, ordinary people who take on forces too big for them. It's about falling in love and how hard it can be. And it's about music--how it can bring us together when we are divided and save us when all seems lost.

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Community Centre | Available |

| Stamford | Available |

| Victoria | Available |

| Victoria | Available |

Other Formats

Browse Related Items

| Subject |

| Record stores > Fiction. Man-woman relationships > Fiction. England > Fiction. |

| Genre |

| Romance fiction. Novels. |

- ISBN: 9780385681230

- Physical Description 324 pages ; 25 cm

- Publisher [Place of publication not identified] : [publisher not identified], 2017.