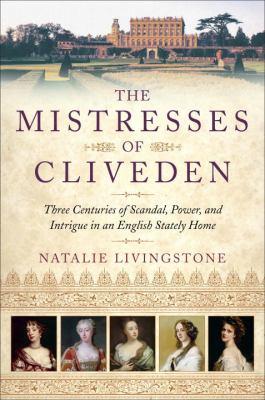

The mistresses of Cliveden : three centuries of scandal, power, and intrigue in an English stately home

Browse Related Items

| Genre |

| Biographies. |

- ISBN: 0553392077

- ISBN: 9780553392074

- Physical Description xv, 494 pages : illustrations (some colour)

- Edition First U.S. edition.

- Publisher New York : Ballantine Books, [2015]

- Copyright ©2015

Content descriptions

| Bibliography, etc. Note: | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

| Immediate Source of Acquisition Note: | LSC 42.00 |

Additional Information

The Mistresses of Cliveden : Three Centuries of Scandal, Power, and Intrigue in an English Stately Home

Click an element below to view details:

Excerpt

The Mistresses of Cliveden : Three Centuries of Scandal, Power, and Intrigue in an English Stately Home

Chapter 1 The Duel Barn Elms, 16 January 1668 In the thin light of a January morning, the Duke of Buckingham galloped towards Barn Elms, the appointed site for the duel he had so long awaited. In springtime and summer, revellers flocked to Barn Elms with their bottles, baskets and chairs, recorded the diarist Samuel Pepys, 'to sup under the trees, by the waterside', but in winter the ground next to the Thames was frozen and deserted. Nevertheless, there was still activity on the river. Nearby Putney was famous for its fishery and was also the point at which travellers going west from London disembarked from the ferry and continued by coach. The harried cries of watermen and the shouts of fishermen returning from dawn trips filled the air as Buckingham neared his destination. The grounds of the old manor of Barn Elms lay on a curve in the river just west of Putney. The land was divided into narrow agricultural plots - some open, others fenced off by walls or hedgerows. Pepys recorded that the duel took place in a 'close', meaning a yard next to a building or an enclosed field - somewhere screened off from passers-by. But as his horse's hoofs thundered along the icy riverbank, Buckingham's thoughts lay on a more distant turf. Anna Maria, the woman who had provoked the duel, was 270 miles away, in self-Âimposed exile in a convent in France. Nine years before, in 1659, Anna Maria Brudenell had married Francis Talbot, 11th Earl of Shrewsbury, but the union had been an unhappy one. He was 36, a wealthy but sedate landowner; she was a pleasure-loving 16-year-old already conscious of her seductive charms. Anna Maria kept a series of lovers but Shrewsbury turned a blind eye, making himself a laughing stock at court. During a trip to York in 1666, she began a new affair, this time with the flamboyant courtier George Villiers, 2nd Duke of Buckingham, and the following summer sexual rivalry between him and another of her paramours, the hot-headed rake Henry Killigrew, exploded in a violent scuffle. This very public fracas made it abundantly clear that Anna Maria had been serially unfaithful, and Shrewsbury's failure to challenge either man to a duel was seen as a dereliction of his role as a noble husband. Anna Maria fled to France in shame. Amid reports that Buckingham was actually hiding Anna Maria in England, Shrewsbury at last summoned the courage to defend his marriage and his name. He challenged Buckingham to a duel and the duke eagerly accepted. Anna Maria exerted an extraordinary hold over a great number of men but she quite simply possessed the duke. 'Love is like Moses' serpent,' he lamented in his commonplace book, 'it devours all the rest.' Pepys reported that King Charles II had tried to dissuade Buckingham from fighting the duel but the message was never received. Even if it had been delivered, Buckingham would probably have taken little heed of the king's wishes. Charles II was more like his brother than his monarch. Buckingham's father, also George Villiers, had been made a duke by Charles I and, when Villiers senior was assassinated in 1628, the king took the Buckingham children into his household. Young George became a close friend of the future king and many of Charles's happiest childhood memories involved Buckingham. The pair spent their student days at Cambridge University and their names appear side by side in the records of matriculation at Trinity College. Buckingham felt little obligation to defer to the king, while Charles tended to turn a blind eye to Buckingham's reckless conduct. Unknown to Shrewsbury, Buckingham had another reason to be riding to Barn Elms that January day in 1668. Shortly after the start of his affair with Anna Maria, Buckingham had viewed a magnificent estate next to the Thames. The site, then owned by the Manfield family, was within easy boating distance of London and included two hunting lodges set in 160 acres of arable land and woods. The estate was known as Cliveden, or Cliffden, after the chalk cliffs that rose above the river. From the lodges the ground dropped sharply towards the Thames, and on the far side of the river flooded water meadows and open land spread out for miles beyond. There had once been a well-stocked deer park on the site and Buckingham knew he could restore the estate to its former glory. He intended to replace the lodge with a large house that would boast the best views in the kingdom. Buckingham bought Cliveden with the pleasures of the flesh at the forefront of his mind. This, he fantasised, would be his grand love nest with Anna Maria, a place for them to freely indulge in their affair - hunting by day, dancing by night. It was Buckingham's obsession with Anna Maria and his dream of a gilded life with her at Cliveden that led him to accept Shrewsbury's challenge. Buckingham's fight with Shrewsbury was not to be an impulsive brawl of the sort seen every night across London's streets and taverns, but a carefully calibrated episode of violence. Although there had been medieval precedents for settling disputes through combat, the duel of honour was essentially a Renaissance invention, imported from Italy. Duelling formalised conflicts between aristocrats, replacing cycles of revenge, usually romantic in nature, with a single, rule-bound encounter. Its outcome served to resolve and annul any other grievances. The duel was part of a new court culture, which placed heavy emphasis on civility and courtesy; when these principles were ignored, duelling provided a means of redress. In the 1660s, after the monarchy was restored, duels became more common and attracted significant public interest and press comment, even if the participants lacked any kind of celebrity status.8 Charles II did issue an anti-duelling proclamation in 1660: 'It is become too frequent,' this stated, 'especially with Persons of quality, under a vain pretence of Honour, to take upon them to be the Revengers of their private quarrels, by Duel and single Combat.' In reality, however, Charles II had no moral objection to the culture of romantic fighting, and in the absence of effective legislation from Parliament, duels were judged on a case-by-case basis. A duel was conventionally initiated with a challenge from the aggrieved party, whose complaint could be anything from the monumental to the trivial. The philosopher Thomas Hobbes wrote that men fought duels 'for trifles, as a word, a smile, a different opinion, and any other sign of undervalue in their Kindred, their Friend, their Nation, their Profession or their Name'. Even if a challenge were accepted, the duel itself could be avoided, either by one of the parties backing down or by a third party intervening. When a fight did take place, the duellists were each required to select two men as 'seconds'. In earlier times the seconds had merely an auxiliary role, carrying weapons and arbitrating, but by the 1660s it had become fashionable for them to engage at the same time as the main combatants - turning the duel into a ritualised piece of gang violence. Nominally, the aim was to prove one's honour by exposing oneself to danger, not to kill the opponent, but inevitably some duels ended in serious injury or death. Excerpted from The Mistresses of Cliveden: Three Centuries of Scandal, Power, and Intrigue in an English Stately Home by Natalie Livingstone All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.