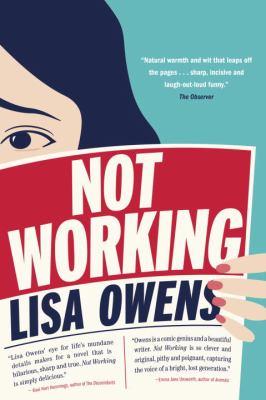

Not working : a novel

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Community Centre | Available |

| Stamford | Available |

Browse Related Items

| Subject |

| Employees > Resignation > Fiction. Job hunting > Fiction. |

| Genre |

| Humorous fiction. Fiction. |

- ISBN: 0385686005

- ISBN: 9780385686006

- Physical Description 243 pages

- Publisher Toronto : Doubleday Canada, [2016]

- Copyright ©2016

Content descriptions

| Immediate Source of Acquisition Note: | LSC 29.95 |

Additional Information

Not Working

Click an element below to view details:

Excerpt

Not Working

1 Wallflower There is a man standing outside my flat wearing khaki-Âgreens and a huge "Free Palestine" badge. "Are you the owner?" he asks, and I turn to see if he is talking to someone else, but there is no one behind me. It buys me a second to remind myself which side of the Israel-ÂPalestine conflict I am on. "I think so, yes," I say, and then with more confidence, because now I'm sure, "Yes, I'm definitely the owner." He scratches his neck, which is gray with dirt. His ears have the same ashy hue. "You need to get the buddleia removed. It's a hazard." "Oh right," I say, looking up to where he is pointing, to a plaster pillar on the front of the building, topped by an ornamental detail. I've never noticed it before, but now I'm embarrassed to see that the paintwork is cracked and filthy. If anyone had asked me to name it--Âif a million pounds had been resting on it--ÂI would have guessed it was called a balustrade. "Does it not serve a structural purpose?" I say. He stares at me, tugging on his beard, which tapers into a slender plait. "It's a weed. It's not supposed to be there," he says, and now I understand: there is a plant sprouting from the top of the thing, a spray of purple flowers. It's quite pretty. "And .â.â. sorry, who are you?" I ask, wondering if he is from the city council, a neighbor or an interfering passerby. "Colin Mason, MBE," he says and offers a dusty hand. I hesitate for a fraction of a second before good manners kick in and I take it. "Claire," I say. "Shall I deal with it, then?" he asks, nodding up at the buddleia. "I'll do a bit of a paint job while I'm up there too." "Mm, just .â.â. I'm going to have to talk to my boyfriend about it first. Because we share ownership. How can I reach you?" "I'll be around," he says. "You'll see me about." I go inside to wash my hand and call Luke. A woman answers, his colleague Fiona. "He's scrubbing up for surgery," she says. "Can I get him to call you back?" "Would you mind just holding the phone to him so I can have a quick word? Two seconds, I promise." There's a fumbling noise and then Luke's voice. "What's up?" "There's a problem with our flat. A buddleia needs removing." "A what?" I sigh. "It's a weed. A purple flowering weed? The guy outside said it needs to go." "What guy?" "Colin Mason." "Who's that?" "He has an MBE. He was pretty adamant." "So what do you want to do? Do you need to call someone? Can I leave it with you? Claire," he says, "I've got to go." "Yes, leave it with me. What do you want to do for dinner?" "He won't be home for dinner," Fiona says. "He's going to be working late." "Oh," I say. I think I'll sit tight on the buddleia thing for a while; see if it develops. Tube Three women opposite talk about the weather as if it's a friend they don't much like. "And that's another thing," says one, leaning in. "My no-Âtights-Âtill-ÂOctober rule has gone straight out the window." Her companions bob their heads, uncross and recross their nylon-Âclad legs. Wallflower My mother phones me on her lunch break. I can hear she's in a cafe. "Where are you?" she asks, as though she's picking up a baffling background cacophony, instead of the silence in my kitchen. "At home." "I see. How's the you-Âknow-Âwhat going?" She means "job hunt": calling it the "you-Âknow-Âwhat" is, incredibly, less annoying than the question itself. "Yep. Fine. Just trying to push on." "Listen, before you go, what do you make of this? I had an awful dream last night that I saw Diane, the .â.â. Diane from work. It was definitely Diane, but in the dream I thought she was someone else, a stranger." Until now I have only heard my mother describe her as "Diane the black receptionist." I have a feeling there is more to come. "Funnily enough"--Âthis is said as though it's just occurred to her--Â"I did see a woman who I thought was Diane yesterday in town, and went to say hello but then realized it wasn't her." She laughs. "Claire, what do you think? Do you think she would have been offended?" "Who," I say, because I can't resist, "Diane or the person you thought was Diane?" "The other lady. Not Diane. Do you think she would have known that I confused her with someone else, with another--Â" "Another woman of color?" I help her out. "Oh," my mother says, "I don't think that's very PC. I don't think you can say 'colored' nowadays." Tube A few seats down the car, there's an old man knitting, bald and cozy in a big white woolen cardigan. I smile at him and raise my eyebrows, and when I do, I see the earrings, purple dangly ones, and realize it isn't an old man at all but a woman, not so old, my mother's age maybe, who has lost all her hair. She grins at me, the needles clicking away, and I keep my eyebrows up, smiling hard at my hands, which lie still in my lap. Wake After the main course is cleared away, the waiters--Âwho are really just teenagers--Âbring out dessert: bowls of melting ice cream and fruit swimming in syrup. I'm sitting at the children's table with the other children. (We're all over twenty-Âfive.) My cousin Stuart, who beneath his suit jacket is wearing a "No Fear" T-Âshirt, asks me what I'm doing these days. "I'm working that out," I say. I've had a lot of wine: it keeps coming and I keep drinking it. "I quit my job two weeks ago so I could take a bit of time to try to figure out why I'm here. Not in a religious way, but I believe everyone has a purpose. Like, how you were made to be in computers. That makes total, perfect sense." I stop, worried suddenly that he's a normal engineer and not a software engineer, but he nods. "Marketing wasn't your calling, then." "Creative communications," I correct him. "Won't lie: I never really knew what that meant." "It .â.â." I prepare to launch into an explanation, then realize I may never need to again, "doesn't matter anymore." "There aren't any spoons," Stuart says, and I beckon one of the teenagers over. "Could you bring us some spoons, please?" I am indignant that I should even have to ask, and my tone is pleasingly chilly. The boy waiter smirks. When he comes back, he's clutching a bouquet of knives, which he releases in a silver cascade in front of me. "No spoons left," he says. "No forks either. We're really busy today." I shake my head. "Unbelievable," I mutter to Stuart as we dole out the knives. I slice off some of the shrinking ice-Âcream island and carefully lift it to my mouth. I look across to the table where my poor grandmother is sitting. Her husband of sixty years is only just in the ground and she's licking a speared peach-Âhalf like a lollipop. During coffee, Stuart's dad, my uncle Richard, gives a speech about Gum. He pokes gentle fun at the pride Gum took in his "war wounds"--Âthe scars from his many operations. "He really did love to show off his war wounds," I say to our table. My cousins nod and smile, murmuring agreement. "And more!" I continue, pointing down at my lap and laughing. "Even after the heart op." "Whoa," says my cousin Faye. "What? Gum used to show you his .â.â.â?" "Oh--Âno, no. 'Show' makes it sound .â.â. It wasn't .â.â. I don't think it was really on purpose or anything," I say. Everyone is looking at me. No one is talking. "Honestly, it definitely wasn't a big deal. At all. I always thought it was--ÂDid no one else have this? How it used to just kind of slip out?" Faye is shaking her head. Her ears, poking through her thin blond hair, have turned red. I glance around at all the other cousins' faces; most are gazing into their coffee. I dump a packet of sugar into mine and stir it with the knife I saved from dessert. Dream At night driving on the motorway, my lights won't turn on, but each passing car has theirs on full beam, dazzling between fretful stretches of darkness. Context is everything "The buddleia (or buddleja bush)," according to one website, "can either be a beautiful flowering garden bush attractive to butterflies or a vile, destructive, invasive weed." Bus I take the bus to the gym I can't really afford anymore. I choose a seat by the window and try to make progress with my book. (I have been reading Ulysses for nearly nine months.) When I've read the same paragraph five or six times, I look up, desperate for some relief from the words. An old guy in a powder-Âblue jacket with long, sparse hair is coming slowly down the aisle. He looks around for a seat, but they're all taken and no one gets up, so like a stoic he sets his mouth and grips the handrail next to him. I think about offering mine, but I'd have to ask the woman next to me to move. She looks important, smartly dressed as if she's going to a meeting. She's reading through some notes and I don't want to disturb her, or make her feel bad that she didn't offer up her seat. I go back to Ulysses and, burning with the effort of pretending I haven't noticed the old guy, I finally make it onto the next page. When the woman next to me gets off, the old man stays where he is. I watch him sway and shuffle with the movement of the bus, dancing in his orthopedic shoes. Gym At the gym, I try to get out of my membership contract. "You'll need to wait until the thirtieth of the month to hand in your notice, and then your contract will end two months after that," the woman whose name badge says frankie tells me. It's Halloween and she is dressed as a witch, with a hat, a cape and her nails painted black. Underneath the cape, she's in a shiny black unitard. "But the thirtieth is a full month away," I say. "Can't we just pretend it's yesterday?" "If only!" she says, rustling a tin of retro sweets at me sympathetically. I take a pack of butterscotches and crunch them two at a time. She looks at her records. "I see you still haven't had your Full-Âbody Analysis. Shall we do that now, as you're here?" I had been putting it off until I got fitter because I wanted to get a better score than Luke, but it's been two years and if I'm leaving, I might as well get it done. She comes around the reception desk and ushers me to a table, taking her plastic broom with her. In response to the questionnaire, I tell Frankie that I don't drink any alcohol or coffee, and that I sleep for nine hours every night. My blood pressure is good and so are my resting levels, but when she tests my aerobic fitness on the treadmill, I'm so eager to impress that I nearly slide off, and my vision goes dark while I gasp for breath. "How often did you say you come here?" Frankie asks, looking at her clipboard. "Have you thought about a personal trainer?" By the time I leave, I've signed up to three one-Âon-Âone sessions with a personal trainer named Gavin, at a specially reduced introductory rate of £99.99. Success I'm not sure if my mother has been storing up material for our conversations, or if it's part of the process of grieving for her father, but these days when she phones, she seems to have an awful lot of awful news to relate. "Pippa from church, in the choir--Âyou know her. The husband, an atheist--Âyou wouldn't have met him. Slipped and fell in the shower: it's touch-Âand-Âgo whether he'll walk again. I've sent Dad out to buy one of those rubber mats. You can't be too careful." And: "Gordon two doors up from us, well, his son-Âin-Âlaw, the policeman--ÂI told you, remember? Depressed. Several attempts, over the years, but they thought he was over all that. Anyway," she says with a sigh, "it would seem this time he did succeed." My next move I go to a cafe to get out of the house and bring my laptop so I can do some career research. There is a table of about eight women, all with babies, and a couple of them are breastfeeding. They're talking about how hands-Âon their husbands are, and while their one-Âupmanship makes me slightly suspicious, I can't deny that the women look great. Their skin is fantastic, and the babies are all so sweet--Âtiny, quiet and content. I'm surfing websites for jobs, but don't know what I'm looking for and all my searches keep returning sales or executive positions way above my earning bracket. A woman comes in who looks about my age, balancing a toddler on her hip, a little girl. The two of them are in matching Breton-Âstriped tops and jeans, and when she orders a coffee, she actually has a French accent. She sits at the table next to me and the child is off: behind the counter, under the table, climbing up the stairs marked no entry. She is delightful; the baristas don't mind at all. I click on a description for a heritage job, which involves writing the blue plaques on buildings where notable figures used to live. I could definitely do that, I think, sum someone up in a couple of words. I consider how I would blue-Âplaque people I know: Luke = "eminent physician"; Paul = "pioneering artist"; Sarah = "educational innovator." I have a harder time with the ones who work in PR and management consultancy, and decide that's because they probably wouldn't deserve a blue plaque anyway. The toddler is at my table, holding out her arms and waving both hands from the wrists, beaming. I do the same and she laughs, runs away, buries her face in her mother's lap saying, "Maman, Maman!" and the mother, who might in fact be younger than me, bends over to murmur a stream of French into her daughter's bright bobbed hair. Excerpted from Not Working by Lisa Owens All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.