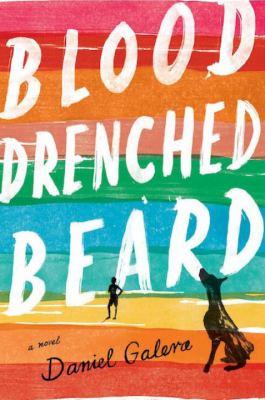

Blood-drenched beard

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Community Centre | Available |

Browse Related Items

- ISBN: 0670068349

- ISBN: 9780670068340

- Physical Description 374 pages

- Publisher Toronto : Hamish Hamilton, [2014]

- Copyright ©2014

Content descriptions

| Immediate Source of Acquisition Note: | LSC 32.00 |

Additional Information

Blood-Drenched Beard

Click an element below to view details:

Excerpt

Blood-Drenched Beard

ONE H e sees a bulbous nose, shiny and pockmarked like tangerine peel. A strangely youthful mouth between a chin and cheeks covered in fine lines, slightly sagging skin. Clean-shaven. Large ears with even larger lobes that look as if their own weight has stretched them out. Irises the color of watery coffee in the middle of lascivious, relaxed eyes. Three deep, horizontal furrows in his forehead, perfectly parallel and equidistant. Yellowing teeth. A thick crop of blond hair breaking in a single wave over his head and flowing down to the nape of his neck. His eyes take in every quadrant of this face in the space of a breath, and he could swear he's never seen this person before in his life, but he knows it's his dad because no one else lives in this house on this property in Viamão and because lying on the floor next to the man in the armchair is the Blue Heeler bitch who has been his dad's companion for many years. What's that face? asks his father. It's an old joke. He gives his usual answer with the barest hint of a smile: The only one I've got. Now he notices his dad's clothes, the tailored dark gray slacks and blue shirt with long sleeves rolled up to the elbows, with sweaty patches under his arms and around his bulging belly, sandals that appear to have been chosen against his will, as if only the heat were stopping him from wearing leather shoes. He also sees a bottle of French cognac and a revolver on the little table next to his reclining chair. Have a seat, says his dad, nodding at the white two-seater imitation- leather sofa. It is early February, and no matter what the thermometers say, it feels like it's over a hundred degrees in and around Porto Alegre. When he arrived, he saw that the two ipê trees that kept guard in front of the house were heavy with leaves and drooping in the still air. The last time he was here, back in the spring, their purple and yellow- flowered crowns were shivering in the cold wind. Still in the car, he passed the vines on the left side of the house and saw several bunches of tiny grapes. He imagined them transpiring sugar after months of dry weather and heat. The property hadn't changed at all in the last few months. It never did: it was a flat rectangle overgrown with grass beside the dirt road, with a small disused soccer pitch in its usual state of neglect, the annoying barking of Catfish, the other dog, the front door standing open. Where's the pickup? I sold it. Why is there a revolver on the table? It's a pistol. Why is there a pistol on the table? The sound of a motorbike going down the road is accompanied by Catfish's barking, as hoarse as an inveterate smoker shouting. His dad frowns. He can't stand the noisy, insolent mongrel and keeps it only out of a sense of duty. You can leave a kid, a brother, a father, definitely a wife--there are circumstances in which all these things are justifiable--but you don't have the right to leave a dog after caring for it for a certain amount of time, his dad had once told him when he was still a boy and the whole family lived in Ipanema, in the south zone of Porto Alegre, in a house that had also been home to half a dozen dogs at one stage or another. Dogs relinquish a part of their instinct forever in order to live with humans, and they can never fully recover it. A loyal dog is a crippled animal. It's a pact we can't undo. The dog can, though it's rare. But humans don't have the right, said his dad. And so Catfish's dry cough must be endured. That's what they're doing, his dad and Beta, the old dog lying next to him, a truly admirable, intelligent, circumspect animal, as strong and sturdy as a wild boar. How's life, son? Why the revolver? Pistol. You look tired. I am, a bit. I'm coaching a guy for the Ironman. A doctor. He's good. Great swimmer, and he's doing okay in the rest. He's got one of those bikes that weighs fifteen pounds, including the tires. They cost about fifteen grand. He wants to enter next year and qualify for the world championship in three years max. He'll make it. But he's a fucking pain in the ass, and I have to put up with him. I haven't had much sleep, but it's worth it. The pay's good. I'm still teaching swimming. I finally managed to get the bodywork done on my car. Good as new. It cost two grand. And last month I went to the coast, spent a week in Farol with Antônia. The redhead. Oh, wait, you never met her. Too late, we had a fight in Farol. And that's about it, Dad. Everything else is the same as always. What's that pistol doing there? Tell me about the redhead. You got that weakness from me. Dad. I'll tell you what the pistol's doing there in a minute, okay? Jesus, tchê, can't you see I'm in the mood for a bit of a chat first? Fine. For fuck's sake. Fine, I'm sorry. Want a beer? If you're having one. I am. His dad extracts his body from the soft armchair with some difficulty. The skin on his arms and neck has taken on a permanent ruddiness in the last few years, along with a rather fowllike texture. His father used to kick a ball around with him and his older brother when they were teenagers, and he frequented gyms on and off until he was forty-something, but since then, as if coinciding with his younger son's growing interest in all kinds of sports, he has become completely sedentary. He has always eaten and drunk like a horse, smoked cigarettes and cigars since he was sixteen, and indulged in cocaine and hallucinogens, so that it now takes some effort for him to haul his bones around. On his way to the kitchen, he passes the wall in the corridor where a dozen advertising awards hang, glass-framed certificates and brushed-metal plaques dating mostly from the eighties, when he was at the peak of his copywriting career. There are also a couple of trophies at the other end of the living room, on the mahogany top of a low display cabinet. Beta follows him on his journey to the fridge. She looks as old as her master, a living animal totem gliding silently behind him. His dad plodding past the reminders of a distant professional glory, the faithful animal at his heel, and the meaninglessness of the Sunday afternoon all induce an unsettled feeling in him that is as inexplicable as it is familiar, a feeling he sometimes gets when he sees someone fretting over a decision or tiny problem as if the whole house-of-cards meaning of life depended on it. He sees his dad at the limits of his endurance, dangerously close to giving up. The fridge door opens with a squeal of suction, glass clinks, and in seconds he and the dog are back, quicker to return than go. Farol de Santa Marta is over near Laguna, isn't it? Yep. They twist the caps off their beers, the gas escapes with a derisive hiss, and they toast nothing in particular. It's a shame I didn't get to the coast of Santa Catarina more often. Everyone used to go in the seventies. Your mother did before she met me. I was the one who started taking her down south, to Uruguay and so on. Those beaches have always disturbed me a little. My dad died up there, near Laguna, Imbituba. In Garopaba. It takes him a few seconds to realize that his dad is talking about his own father, who died before he was born. Granddad? You always said you didn't know how he died. Did I? Several times. You said you didn't know how or where he'd died. Hmm. I may have. I think I did, actually. Wasn't it true? His dad thinks before answering. He doesn't appear to be stalling for time; rather, he is reasoning, digging around in memory, or just choosing his words. No, it wasn't true. I know where he died, and I have a pretty good idea how. It was in Garopaba. That's why I never liked going to those parts much. When? It was in 'sixty-nine. He left the farm in Taquara in ... 'sixty-six. He must have wound up in Garopaba about a year later, lived there for around two years, something like that, until they killed him. A short laugh erupts from his nose and the corner of his mouth. His dad looks at him and smiles too. What the fuck, Dad? What do you mean, killed him ? You've got your granddad's smile, you know. No. I don't know what his smile was like. I don't know what mine's like either. I forget. His dad says that he and his granddad resemble each other not just in their smiles but in many other physical and behavioral traits. He says his dad had the same nose, narrower than his own. The wide face, the deep-set eyes. The same skin color. The granddad's indigenous blood had skipped his son and come out in his grandson. Your athletic build, he says, that came from your granddad for sure. He was taller than you, about six foot. Back then no one practiced sports like you do, but the way he chopped wood, tamed horses, tilled the soil, he'd have given today's triathletes a run for their money. That was my life too until I was twenty. Don't think I don't know what I'm talking about. I used to work on the land with Dad when I was young, and I was impressed by his strength. Once we went looking for a lost sheep, and we found it over near the fence, almost on the neighbor's side, in a bad way. About two miles from the house. I was wondering how we were going to get the pickup there to take it home, already imagining that Dad was going to send me to get a horse, but he hoisted the ewe onto his shoulders, as if it were hugging his neck, and started walking. A sheep like that weighs ninety to a hundred pounds, and you remember what it's like out there: all hills and rocky ground. I was about seventeen and asked to help carry it, 'cause I wanted to help, but Dad said no, she's in place now. Taking her off and putting her back will just be more tiring. Let's keep walking, the important thing is to keep walking. I probably wouldn't have been able to bear that animal on my back for more than one or two minutes anyway. I was never scrawny, but you two are a different breed. You're even alike in your temperament. Your granddad was pretty quiet, like you. The silent, disciplined sort. He wasn't one for idle chatter, spoke only when he had to, and was annoyed by people who didn't know when to shut up. But that's where the similarities end. You're gentle-natured, polite. Your granddad had a short fuse. What a cantankerous old man he was! He was famous for pulling out his knife over any little thing. He'd go to a dance and wind up in a brawl. To this day I don't know how he got into so many fights, because he didn't drink much, didn't smoke, didn't gamble, and didn't mess around with other women. Your grandma almost always went out with him, and it's funny, she didn't seem bothered by this violent side of his. She liked to listen to him play. He was one hell of a guitar player. She once told me he was the way he was because he had an artist's soul but had chosen the wrong life. She said he should have traveled the world playing music and letting out his philosophical sentiments--that was the expression she used, I remember clearly--instead of working the land and marrying her, but he had missed his true calling when he was very young, and then it was too late, because he was a man of principles and changing his mind would have been a violation of those principles. That was her explanation for his short fuse, and it makes sense to me, though I never knew my dad well enough to be sure. All I know is that he was forever dealing out punches and whacking people with the broad side of his knife. Did he ever kill anyone? Not that I know of. Producing his knife rarely meant stabbing someone. He did it more to show off, I think. I don't remember him coming home hurt, either. Except that time he got shot. Shot? He was shot in the hand. I told you about that. True. He lost his fingers, didn't he? In one of these fights, he lunged at a guy, and the guy fired his gun to give him a fright. The bullet grazed Dad's fingers. He lost a bit of two fingers, the little finger and the one next to it. On his left hand, the one he used for picking. A few weeks later he decided to take up the guitar again, and in no time he was playing just as well as he always had or better. Some people said he'd improved. I can't say. He developed a crazy picking technique for his milongas. I guess those two fingers don't make much difference. I don't know. They certainly didn't make any difference for him. What really did him in was when your grandma died of peritonitis. I was eighteen. Life was never the same again, not for me or for him. His dad pauses and takes a sip of beer. Did you leave the farm after Grandma died? No, we stayed on for a while longer. About two years. But everything started getting strange. Your granddad was really attached to your grandma. He was the most faithful man I've ever known. Unless he was really discreet, had secrets ... but it was impossible in a place like that, a small town where everyone knows everything. The women used to fall in love with your granddad. A bold, strapping man, a guitar player. I know because I went to the dances and saw single and married women falling all over him. My mother used to talk about it with her friends too. He could have been the biggest Don Juan in the region and was insanely faithful. Blondes galore all wanting a bit, wives looking for some fun. I myself lived it up. And Dad would give me a piece of his mind. He said I was like a pig wallowing in mud. Ever seen a pig wallowing in mud? It's the picture of happiness. But your granddad's moral code was based on the essential, almost maniacal notion that a man had to find a woman who liked him and look after her forever. We used to fight a lot because of it. I actually admired it in him when my mother was still alive, but after she died, he maintained a ridiculous sense of fidelity that no longer served any purpose. It wasn't exactly mourning, because it wasn't long before he was back at the dances, livening up barbecues, playing the guitar and getting into fights. He took to drinking more too. The women were all over him like flies on meat, and little by little he let his guard down to this one or that one, but in general he was mysteriously chaste. There was something there that I never understood and never will. We started growing apart, him and me. Not because of that, of course, though we didn't see eye to eye on how to deal with women. But we started to argue. Was that when you came to Porto Alegre? Yeah. I came in 'sixty-five. I'd just turned twenty. But why did you and Granddad argue? Well ... I don't really know how to explain it. But the main thing was that he thought I was lazy and a womanizer who didn't want anything out of life and wasn't even remotely interested in the farm, work, or moral or religious institutions of any kind. And he was right, though he was a bit over the top in his assessment. I think he just got fed up and couldn't be bothered trying to set me straight. I wasn't really such a lost cause, but your granddad ... anyway. One day I experienced his famous short fuse first hand. And the upshot was that he sent me away to Porto Alegre. Did he hit you? His dad doesn't answer. Okay, forget I asked. We knocked each other about a bit, so to speak. Oh, what the fuck. At this stage in the game, none of it matters anymore. Suffice to say that he gave me a working over. And the next day he apologized but announced that he was sending me to Porto Alegre and that it would be better for me. I'd been to Porto Alegre several times before and knew right away that he was right. I felt big here right from the first day. I went to technical school. In a year and a half I'd opened a printer's shop over in Azenha. In three years I was making good money writing ads for shock absorbers, crackers, and residential lots. Stylize . He chuckles. The glasses for eyes with style . And worse. Okay. But Granddad was killed. Excerpted from Blood-Drenched Beard by Daniel Galera All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.