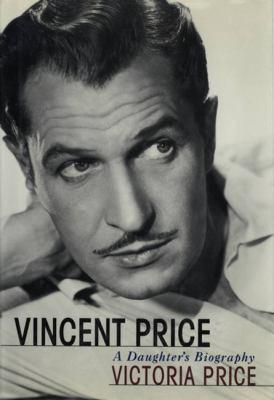

Vincent Price : a daughter's biography

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Community Centre | Available |

Browse Related Items

| Subject |

| Price, Vincent, 1911-1993. Actors > United States > Biography. |

| Genre |

| Biographies. |

- ISBN: 0312242735

-

Physical Description

print

viii, 370 pages : illustrations - Edition 1st ed. --

- Publisher New York : St. Martin's Press, 1999.

Content descriptions

| General Note: | Includes index. |

| Immediate Source of Acquisition Note: | LSC $42.99 |

Additional Information

Vincent Price : A Daughter's Biography

Click an element below to view details:

Excerpt

Vincent Price : A Daughter's Biography

Vincent Price: A Daughter's Biography I. Renaissance Man I BELIEVE IN YOU MY SOUL ... THE OTHER I AM MUST NOT ABASE ITSELF TO YOU, AND YOU MUST NOT BE ABASED TO THE OTHER. --WALT WHITMAN, SONG OF MYSELF 1 MY FATHER, VINCENT Leonard Price Jr., was born in St. Louis, Missouri, on May 27, 1911, the fourth and last child of Vincent Leonard and Marguerite Willcox Price. He described his family as "well-to-do, not rich enough to evoke envy but successful enough to demand respect." But this sunny description belied a more complex financial legacy--one that had a profound impact on the lives of all the Price men. Thus, to tell my father's story, I must begin with the life of my great-grandfather, Dr. Vincent Clarence Price. His vicissitudes began a saga that became a cautionary tale to his famous grandson, who bore his name. Although virtually nothing is known about his predecessors, family records confirm that Vincent Clarence Price was born in Troy, New York, on December 11, 1832. He was of Welsh descent, a fact borne out by his looks--he was, as my father would later write, "a wonderfully black-haired, black-mustached, 'black' Welshman." The earliest published mention of Vincent C. Price appears in the 1848 Troy City Directory, which lists the sixteen year old working as a clerk. His name appears in the directory again as a clerk in 1850, then as a bookkeeper at the American Hotel in 1852. During this time he attended medical college, from which he graduated in 1852. Indeed, by 1853, the city directory lists V.C. Price as a wholesale druggist. In the fall of 1853, however, the young druggist moved to Buffalo to study homeopathic medicine and chemistry at New York College. Although his background was working class, Vincent C. was encouraged to further his medical education by Dr. Russell J. White, an analytical physician and father of his bride-to-be, Harriet Elizabeth, a striking young woman of patrician bearing and even-featured good looks. According to Price family lore, Dr. White was not only a prominent citizen and a successful doctor but also reportedly a descendant of Peregrine White, the first child born as the Mayflower landed in Plymouth Harbor in 1620. Much was made of this distinguished heritage, particularly by Vincent Clarence himself, who left no record of his own family history but frequently referred to his wife's more illustrious origins. His enthusiasm for the White -Mayflower connection would be passed down through generations of the Price family, including to my father, who relished the idea of his American blue-blood ancestry. However, the Price accounts of the distinguished White lineage appear to be flawed; the purported family genealogy leading back to Peregrine White cannot be confirmed by Mayflower records. Although he lived and attended school in Buffalo, Vincent C. frequently returned to Troy to visit his fiancée. On March 28, 1855, the couple were married at the White home in Troy. After their marriage, Harriet and V. C. set up residence near the collegein Buffalo where, ten months later, their son Russell Clarence was born. That spring, Dr. V. C. Price graduated with an M.D. in pharmaceutical chemistry. A year later, Harriet gave birth to their second child, Ida Helena. Numerous versions of the early years of Dr. Price's career have been passed down, undoubtedly mingling fact and fiction. As my father told it, after graduating from medical college with a wife and two young children to feed, the young homeopathic doctor and chemist began the hard work of establishing his own practice. He soon found, however, that he faced a serious impediment. Facial hair was in fashion in the mid-1850s, and young Price had always had difficulty growing a full beard--a deficit that emphasized his naturally youthful appearance. Prospective patients seemed wary of his youth, and he found it difficult to build a clientele. After a few rough years, the doctor, his wife, and their two babies were forced to move in with his parents. In his spare time, in an effort to help out around the house, he began experimenting with chemical formulas in an attempt to help his mother's neighborhood-renowned biscuits to rise more perfectly. In the process, Vincent C. Price invented baking powder. Realizing the commercial potential of his discovery, he patented his invention ... then went out into the world to seek his fame and fortune. According to his lengthy obituary in the Chicago Tribune of July 15, 1914, however, the man who would become "one of the housewife's best friends" was still in college when he invented baking powder. "It was more than sixty years ago that Dr. Price mixed the world's first cream of tartar baking powder. The doctor's mother had a reputation as a biscuit maker. But her biscuits were not for herself. She could not digest them. Price, then a student in a school of pharmacy, sat watching his mother one day as she kneaded biscuit dough. Then the great idea came to him. He returned to his laboratory and began a series of experiments, which ended with the discovery that the argols, left in the vats as the precipitation of the grapes in wine manufacture, when refined not only did away with the injurious effects of hot biscuit, but also greatly facilitated the work of making them. Soon after a new 'household help' appeared on the market--Price's baking powder." Whatever the true story may be, after patenting his invention Vincent C., like so many nineteenth-century Americans, set out to find prosperity in the West. In 1861 he moved his young family to Waukegan, Illinois, a small but thriving Lake Michigan port city, forty miles north of Chicago, and established their home there. Waukegan had been founded by French explorers two centuries before. By 1860, Waukegan had become one of the busiest harbors on the Great Lakes, boasting over a thousand sailings a year; the city was well enough established to attract a visit from Abraham Lincoln, who spent a night there during his first campaign tour. Dr. Price's intuition about Illinois proved correct. Not only was he able to establish both a family home and a thriving medical practice in Waukegan, he also pursued his dream of marketing his invention by establishing a business partnership with banker Charles R. Steele. Together they purchased a small factory in Chicago, where their company, Steele & Price, began to manufacture Dr. Price's Cream Baking Powder. According to the Tribune obituary, however, "Price did not create a market for his baking powder, enormous as the sales became in a few years, without great effort and many discouragements. His little Chicago plant turned out only a few pounds a day, but he had difficulty in disposing even of that. Personal appeals to grocers and finally a personal, house-to-house, back-door canvassing campaign at last built up a demand. Advertising did the rest." Indeed, within a few years, Dr. Price became a household name and hisbaking powder was sold across the country. His success led him to conduct other food experiments; soon he introduced cornstarch for culinary uses, patented the first fruit and herb flavoring extracts as well as vegetable colorings, manufactured breakfast foods, and even published popular cookbooks. By his fiftieth birthday, Dr. V. C. Price was a multimillionaire. The small house he had purchased at 719 Grand Avenue was razed in 1888 and a larger, more modern home was built on its site for his ever-expanding family--a glorious three-story Queen Anne-style mansion complete with a castlelike turret, dormers, gables, ornate chimneys, and stained glass windows. In addition to Russell and Ida, Harriet had given birth to three more children: Emma Frances (in 1862), Guerdon White (in 1864), and Vincent Leonard (in 1871). In 1880, when Harriet was thirty-six and her husband thirty-eight, Blanche Castle was born, but just over a year later she succumbed to cholera. Dr. Price recorded his grief in the family Bible: "Our home is in mourning. Our home circle is broken. Our darling Blanche died last night." Despite the loss of their youngest child, V. C. and Harriet found joy in the growth, education, and marriages of their surviving children. Dr. Price placed great stock in schooling. Russell was educated at Beloit College and Harvard Medical School before joining his father's company. Guerdon studied at Racine College before also joining the family business, and both the girls received a solid education. As Russell, Ida, Emma, and Guerdon came to maturity, their father built large homes for them and their families on adjoining properties on Grand Avenue, establishing the Prices as one of the most prominent families in Waukegan. Vincent Leonard, seven years younger than his closest sibling, also had meticulous attention paid to his education. After attending the Waukegan public schools, he was sent to the Racine College Grammar School in Wisconsin and prepared for college at the University School in Kenosha, Wisconsin. Among his classmates at the exclusive college preparatory academy was an impetuous and talented younger boy named Richard Head Wells. Price and Wells shared an interest in dramatics and took time away from their studies to put on an extravagant magic show for the school. Some forty-five years later, the younger sons of Price and Wells--Vincent Jr. and Orson (who added an 'e' to become Welles)--would work together as two of the rising young Broadway stars of the 1930s. In 1884, Dr. Price had bought out his business partner and consolidated his holdings as the Price Baking Powder Company. His eldest son, Russell, had rapidly risen to the position of vice president. In the early 1890s, however, Dr. Price decided to sell his interest in the company, leaving Russell to continue as president. Dr. Price had hoped to retire a fairly young and very wealthy man; in the end, though, it would appear that his skill at invention was not matched by his skill at investment, and the Panic of 1893 virtually wiped him out--an event that, if one believes the family stories, had cataclysmic consequences for his youngest son, Vincent Leonard Price. In 1893, Vincent Leonard, then twenty-two, was finishing his junior year at Sheffield Scientific School at Yale University when his father called him home. Although the handsome, mild-mannered young man had an aptitude for the sciences, he also evinced a strong interest in the arts, particularly English literature and poetry. Unlike his older brothers, Vincent was not sure that he wanted to follow in their father's footsteps and become a businessman. As a junior in college, he had been blissfully unconcerned with exact plans for his future. Nonetheless, with the catastrophic losses suffered by his father, he realized that he had no choice but to return home and find work. According to my father, Vincent Leonard took an interest in one of Dr. Price'sholdings, a company so deeply in the red that it was said even the creditors had overlooked it. But a detailed retrospective of the career of Vincent Leonard Price, published half a century later, notes that Vincent's career began in 1894 at the Hill-Rodda Company in Chicago, where he worked as a stenographer. Hill-Rodda Company, this account tells us, was later purchased by Dr. Price with his sons Russell and Vincent L., and other investors, when it was incorporated as the Pan Confection Company. Vincent L. Price acted as manager, secretary, and treasurer for his father, who by the turn of the century was president of the Lincoln National Bank and the Price Cereal Products Company, as well as Pan Confection. Despite his losses in 1893, apparently, the doctor did manage to retain some of his financial holdings; in his 1914 Tribune obituary, he was "reputed to be a millionaire several times over." And yet the story survived somewhat differently in the annals of family tradition: My father always maintained that Dr. Price lost all his money in the crash and died a poor man. Whatever the precise circumstances of Vincent Leonard's removal from Yale, the end result was that he became a businessman. If he had harbored aspirations for a creative life, he dutifully gave them up to work, like both his brothers, for his father. But against all odds and counter to his dreams of a creative life, Vincent Leonard Price proved a shrewd businessman, going on to become one of the most respected leaders of the American candy business. Within the confectionery industry he was noted for his "kindness, generosity, and high ideals to the virtues of truth and love of his fellow man." So profound was his influence that twenty years after his death an article appeared in the newsletter of the National Candy Association, of which he had once been president, naming him one of the most respected industry leaders of the twentieth century. Despite Vincent Leonard's kindness, humility, and generosity of spirit, his own family would come to suspect that, in devoting his life to a successful business career, this remarkable man had been deprived of the life he had wanted to live. Decades later, his children still wondered, What if Dr. Price had remained a multimillionaire? What if their father had been able to pursue a career of his own choosing? And so the mythology of Dr. Price's moment of remembered failure, and its lasting effect on his family, took on a life that extended beyond that of his own children. My father was enthralled by his family history. To him, Dr. Price was a fantastical figure. In his 1958 autobiography, I Like What I Know, Vincent Price wrote of his grandfather, "He had been very rich and, I gathered, rather racy ... . I always regretted that my father's father had not lived long enough for me to know him. The history of his wealth and his vocabulary had made him my favorite relative. I also resented his dying poor." The stories of Dr. Price's financial failings became grist for the mill of many more Price family shortcomings, which his grandson both rued and recounted: "I vaguely recall something about a covered wagon from New York getting stuck in the mud in Chicago, and because that was a sign of some sort, these particular ancestors bought the adhesive spot, which, after they sold it, inevitably turned out to be the Loop--worth at least a million an acre. My family has a startling history of such misadventures. For instance, my father tried, nay pleaded with some of his friends to pool together and buy stock in Ford. Nothing. They didn't. He didn't. My grandfather was offered stock in every paying gold mine in the Western hemisphere and turned it all down to buy nonpaying ones anywhere. The only member of the whole outfit who hit the jackpot was a delightfully debauched uncle who bought half the state of Oklahoma (the right half), made millions, and was rumored to have owned half of a famous opera singer (the right half). Unfortunately, noone ever spoke to him; and my family, being honest, if not smart, only spoke about him after he made good. Proof of my family's misadventures came to light years later when we unearthed enough magnificently engraved but worthless stocks to paper a small room--which I did in a New York apartment. I hope none of them turn out to be good ... I've moved." Throughout his life, my father often returned to the tales of his grandfather's financial misfortunes and his own father's consequent self-sacrifice. Indeed, as a young man, Vincent Price's determination to make his career in the arts was heightened by his belief that his father's life had been irrevocably changed for the worse by his grandfather's monetary troubles. And throughout that career he maintained an uneasy relationship with money, forever juggling the fear of not making any, or somehow losing all of it, with the determination never to be forced into doing something that would denigrate his artistic integrity. Though he often joked about his grandfather, "I'll never forgive him for losing all that money," in truth, to Vincent his own family history was no laughing matter. My brother, Vincent Barrett Price, maintained that "Dad always had his father and Vincent Clarence in the back of his mind. He was the youngest son in a family of men who were forced into doing exactly what they didn't want to do. It must have been terrifying for him, because he had this burgher mind about everything. He had these old tapes in his mind all his life--terrible fears. Fears of inadequacy, fears of poverty. He never was poor, but he always played like he was poor. I think he was under a huge amount of pressure." This troubled legacy would influence the whole course of my father's life. Vincent Leonard Price's older brother Guerdon married Eunice Cobb in 1884. They lived on Grand Avenue, just down the street from the Price mansion. Tragedy struck in November 1891, when twenty-eight-year-old Guerdon, by then the father of two sons, was killed accidentally in Colorado. Three years later, however, Guerdon's younger brother, Vincent Leonard, married Eunice's Cobb Price's niece, Marguerite Cobb Willcox, giving both families something to celebrate. Born and raised in Mineral Point, a wealthy county seat in the beautiful rolling hills of Southwestern Wisconsin, Marguerite Willcox descended from a family whose American roots went back over eight generations. Her illustrious ancestors included at least two soldiers who fought in the American Revolution, a fact of which Marguerite was particularly proud since it qualified her for membership in the Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution. On her father's side, Marguerite was a descendant of the Desnoyers family of Paris, France. Pierre, called Pepe, had crossed the Atlantic in the late eighteenth century, settling in what is now the Detroit area, and becoming one of the first silversmiths in the Midwest. He developed a reputation for fine workmanship and, more interestingly, for his ingenuity in creating artifacts inspired by his environment. Among these were small headbands of silver, complete with protruding silver feathers, which he used as barter with the local American Indian tribes on the Michigan peninsula. On the maternal side, Marguerite descended from a line of strong-willed women with whom she turned out to have much in common. She was particularly intrigued by her great-grandmother, who had married the six-foot-eight-inch captain of a China clipper. He lavished all the silks of the Orient on his beautiful wife until she underwent a religious conversion and took to wearing only black. As my father recalled in I LikeWhat I Know, "From the gorgeous silks she made an endless series of patchwork quilts as penance. Mother cherished them all, as she cherished this legend, even though she would never have thought of emulating it, and the quilts were neatly folded at the foot of every Early American bed in the house." Marguerite's own mother, Harriet Louise Cobb, a strong-willed and liberal-minded woman, married Henry Cole Willcox of Detroit on New Year's Day, 1874. Five months after the wedding, Willcox was tragically drowned, leaving Harriet four months pregnant. On October 28, 1874 she gave birth to a healthy daughter, Daisy Cobb Willcox. A pudgy brown-haired girl with a resolute expression, Daisy showed her distinctive style and determination even when very young, telling anyone who would listen that she despised her name and that when she was old enough she would have it changed. Daisy, she liked to announce, was a name that should only be given to cows. And she was true to her words, striding into court at age twelve and succeeding in changing her name to the French Marguerite. With the help of her own mother, Harriet Willcox raised her headstrong daughter alone for eleven years. Then, in December 1885, she remarried. Although one might imagine that Marguerite would have resented anyone who took away her mother's attention, she unreservedly adored her new stepfather. Born in Ireland, Hans Mortimer Oliver was an English sea captain who perfectly fitted Marguerite's idea of a worldly adventurer. Having never known her father, she idolized everything about Captain Oliver, not least his aristocratic English ancestry. His tales of world travels and his seafaring adventures gave young Marguerite her first glimpse of the glamorous world awaiting her outside of provincial Mineral Point. She immediately adopted his lineage as her own, dutifully hanging framed reproduction portraits of his ancestors in each home in which she lived throughout her lifetime. Her son would later write, "Mother called the reproductions 'The Pirates' just as a come-on to get the chance to explain further, which she always hastened to do. They were the elegantly dressed, in lace and armor, ruddy-cheeked, enormous-nosed antecedents of my British step-grandfather." Marguerite certainly never intended to stay in Wisconsin, but her marriage into the wealthy Price family in Waukegan, forty miles from Chicago, was undoubtedly her first major step away from home. Apparently her own family was thrilled with the match, for as soon as Vincent Leonard and the twenty-year-old Marguerite were married, Harriet and Captain Oliver embarked on a series of journeys around the world. At first the union of this imposing young woman and the gentle and mild-mannered Price might have seemed an unlikely one, but Vincent Leonard Price would prove an ideal husband, and a perfect audience for his wife's dramatic approach to life. As their youngest son, my father, would later comment, "If ever there was a woman who knew what she wanted, it was my mother. Father was beatified by her the day she set eyes on him, and he became a full-fledged saint as the years rolled by. They were married for fifty-three years, until death did them part, and he sat back to wait out the few years until he could join her." Marguerite and Vincent settled in Waukegan, and while Vincent commuted to work in Chicago, Marguerite gave birth to their first two children: Harriet, called Hat, in 1897, and James Mortimer, called Mort, in 1899. By the turn of the century, Vincent Leonard Price's business acumen had put him in a position to better himself financially. In 1902, he went into partnership with two St. Louis businessmen, arranging the merger of the Pan Confection Company with two other small candy manufacturers to form the larger National Candy Company. As vice president of a growing firm seeking to establish anational headquarters and build business, Price chose St. Louis, Missouri. The timing could not have been better. Two years later, in 1904, the city proudly hosted both the World's Fair and the Olympic Games. The National Candy Company set up a booth at the fair, flooding them with customers from around the world and starting them on the road to extraordinary success in the candy industry. VINCENT PRICE: A DAUGHTER'S BIOGRAPHY. Copyright © 1999 by Victoria Price. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information, address St. Martin's Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010. Excerpted from Vincent Price: A Daughter's Biography by Victoria Price All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.