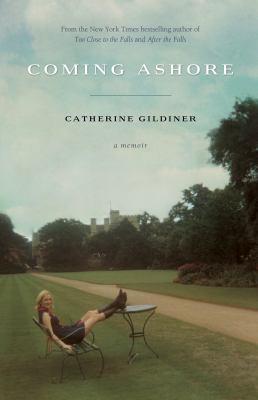

Coming ashore

Canadian psychologist and novelist Catherine Gildiner tells of her life in the late '60s when she recited verse in the classrooms of Oxford University, arranged a date with Jimi Hendrix, and taught inner city kids literature.

Browse Related Items

| Subject |

| Gildiner, Catherine, 1948- > Childhood and youth. Women psychologists > Ontario > Toronto > Biography. College students > Great Britain > Biography. Teachers > Ohio > Cleveland > Biography. |

| Genre |

| Autobiographies. |

- ISBN: 1770412255

- ISBN: 9781770412255

-

Physical Description

print

xiv, 391 pages : illustrations - Publisher Toronto : ECW Press, [2014]

- Copyright ©2014

Content descriptions

| Immediate Source of Acquisition Note: | LSC 27.95 |

Additional Information

Coming Ashore : A Memoir

Click an element below to view details:

Excerpt

Coming Ashore : A Memoir

Chapter Two Special Delivery That evening as I got ready for my first social outing in England, I wondered what a high table dinner was -- a table on stilts? I wore my only dress, a tie-dyed orange, red and turquoise mini with a halter top that tied at the back of my neck. It wasn't right for January at Oxford (or actually anytime at Oxford) but how was I supposed to know how cold it was inside ? I figured it was no big deal to wear a dress that left me overexposed since I had to wear the black gown on top anyway. I also wore red patent-leather shoes with red, white and blue-checkered laces. They looked like old fashioned tap shoes from 42nd Street except they had enormous platform heels. Teetering in my heels, I clomped down the narrow winding stairs in my mini-dress and much-too-large robe that dragged on the ground like a wedding train in mourning. Because the stairwell was more like an educational silo than a normal staircase, the sound of my slapping shoes was magnified by the echo. I walked down the stairs and doors swung open as I passed them. The first guy to pop his head out was Marcus Aaronson. He was short, slight and had brown curly hair that fell in unruly corkscrews on either side of his centre part. He wore a maroon sweater and a Trinity tie. He scowled, saying, "Oh I thought I heard a blacksmith's hammer," and then abruptly closed his door. As I wound down to another floor, a guy confidently strolled out of his rooms into the narrow staircase. He looked quite dapper, in a calculatedly casual sort of way, in a crumpled wool sports jacket and Oxford cloth white shirt, baggy black khakis, and black leather boots. I later learned this was the consciously dishevelled look that so many English graduate students affect while still technically following the dress code called subfusc . ( Subfusc is Latin for dark/dusky colour. I had to go out and buy all black skirts and black tights. With my yellow hair I looked like a pencil in mourning.) He was slightly built but tall and had fashionably shaggy blond wavy hair, royal blue eyes and an aquiline nose. He looked a bit like Virginia Woolf on steroids, but then again so did many of the men I'd seen from my window. He screamed landed-gentry-with-edge. I was sure that he was the man called Clive Hunter-Parsons who Reggie said was so universally admired. "Hark," he said, cupping his hand to his mouth and addressing the man who lived on the floor, "time's horses gallop down the lessening hill." I was indeed clomping along, and as the shoes flipped off my narrow heel when I walked, they made a second echoing bang. The guy from one flight down yelled up to where we stood, "I feared it was a herd of wild Trojan horses, but fortunately we are not at war." "Ah," the blond boy added, "we can rest at ease. It is only the descent of the fair sex, so to speak." I grabbed the railing as the spiral turned and I teetered against the wall, silencing my astonishingly loud foot clatter. I did manage to remember a line from Milton and, leaning against the wall to steady myself, said, "No war or battle's sound, / was heard the world around." The blond gave me the next line: "Nothing but a battle lost can be half so melancholy as a battle won." Well, I was out of Ohio now. That was for sure. I finally made it to the first floor and out crawled the only double X chromosome I'd yet to see, presumably the New Englander, Margaret-Ann Mitchell. She wore one of those Laura Ashley sackcloth dresses, drawn in by a thick black hand knit sweater and flat boots that look like they were made by some local New England hippie turned leather worker. Her long, straight strawberry-blond hair parted in the middle and drooped around her freckled face. Her black gown was also dragging on the ground. She made eye contact with me in the stairwell and blushed to the point that her face matched her hair. "Excuse me," she mumbled and ran off toward the dining room, avoiding any further eye contact. While I stood leaning against the curved wall of the staircase, trying to get my bearings and to remember where the dining hall was located, the blond guy passed me, accompanied by a dark-haired guy who had also exited his rooms in search of the heifer who was plodding down his stairwell. The blond, whose waves danced when he moved, carefully pushed open the door for me and said, "Welcome to stairwell number seven. I am Clive Hunter-Parsons and this less-esteemed colleague is Peter Andover." "I am Helen of Troy," I said, teetering on my shiny red toes. "Then you won't mind our Spartan conditions," said Peter, the plainer guy who lived below the handsome guy named Clive. Peter could have been considered handsome as well if he had not been standing next to the imposingly tall, willowy Clive. While Clive looked relaxed and perpetually amused, Peter looked earnest, like the men who have their pictures in The Economist . "Reggie led me to believe we might eat together -- as a stairwell," I said lamely, hoping they would invite me. "Not tonight, Helen. We understand you are placed at the high table," Peter said. "Launching a thousand forks," I added. Clive, Peter and I walked into the magnificent hall dining room with coffered ceilings and walls covered with dour portraits of famous alumni. I always sat under Sir John Willes, Chief Justice of Common Pleas, 1737. All the long, dark tables were lined up in solemn rows with benches. The room actually resembled the one on TV that Robin Hood used to swing through when he'd surprised the Sheriff of Nottingham at mealtime. One huge table at the far end of the room was perpendicular to the rest and was placed on a separate dais a few steps up from the others. You didn't have to be Queen Elizabeth to figure it was the high table. It was filled with white-haired men, some of whom looked older than any professor I'd ever seen, including all those who had crawled up to emeritus status. Clive tapped my shoulder, saying, "You don't wear gowns at high table." Uh-oh. I'd counted on this robe to cover my halter-top mini. Remembering the Mary Kay Cosmetic School saying, "Fake it till you make it," I threw the black gown on the chair by the door, strode up to the high table and asked, "Is one of you Professor Beech?" "I beg your pardon?" one old codger said. Another smiled and said, "May I offer you a seat." This guy was at least ninety and could have been a portrait on the wall. He could barely stand up to shake my hand. His shirt looked like it had been thrown in the wash with black socks, taken out while wet and then had wrinkles ironed into it. He had cut himself shaving and had a little piece of ragged cloth covering the bloody nick on his scrawny gullet. We were interrupted by the approach of a fat man with strange lower teeth that actually poked out of his mouth and rested on his upper lip when his mouth was closed. "Good evening. Miss McClure, I presume." "Professor Beech?" "Ah, welcome to the adamantine island chained to the shifting bank of the Channel. I see you met our esteemed poet and guest of honour this evening? You've been placed next to him for mutual dining pleasure." While I nodded assent, the esteemed poet said, "Ye--es." I had never heard the word yes spoken in two syllables. Professor Beech scuttled (as fast as a man whose silhouette matched that of Alfred Hitchcock could scuttle) back to his end of the table, saying we would meet in "his rooms" tomorrow afternoon. That sounded kind of creepy to me. As I sat down next to the esteemed poet I blathered, "Sorry I'm late. That stairwell is a challenge in these shoes." "Winding ancient stair; Set your entire mind upon the steep ascent," the esteemed poet said. By this point I was too embarrassed to ask his name. Everyone else seemed to know him. " Hey Yeats." Thank God I'd recognized him. "I love that guy." "As do I." "You know him too?" I asked. "I knew him quite well." "Me too." "He gave me much help in dark times," said the esteemed poet. "Oh. You knew him as in knew the man not just the poetry ." "If one ever knows another." "Wow!" Wanting to keep the conversation going, I added my own brush with celebrity: "I knew Marilyn Monroe." He turned and looked at me with true interest for the first time. "Do tell." I can spin a yarn for hours, so I told him the full version of when Roy and I delivered Nembutal to Marilyn Monroe while she was filming Niagara in the 1950s. I told how she answered the door in a slip and bra and had chipped nail polish. "I say ," he added, "do please press on." Neither of us noticed that the room was quiet and when we finally looked up we met hundreds of eyes looking expectantly at us. The esteemed poet had been introduced to say grace but neither of us had heard. He stood up really slowly, favouring one leg, and said by way of apology, "The peril of discussing Yeats is that all else recedes." He was great on his feet, never used a note and spoke in a definitive, yet warm voice for five or ten minutes. He said grace in Latin and in English and then said that tonight might be a perfect night to quote Yeats. He said you can be assured of a poet's genius when he always has a line or two that expresses exactly your sentiments at the present moment. He turned to me and said, "God be praised for woman That gives up all her mind, A man may find in no man A friendship of her kind That covers all he has brought As with her flesh and bone . . ." He recited the whole poem and smiled at me as he sat down. When dinner was over, I helped the doddering poet down the stairs, and while patting my hand, he again quoted Yeats: "And what rough beast, its hour come round at last / Slouches toward Bethlehem to be born." To this day I don't know his name. I shake my head now thinking of what the Barson called "my plethora of errors" upon arrival. The seat next to the guest of honour was saved for Professor Beech, who'd been one of the esteemed poet's students, and I had blundered into it. My outfit combined with my Marilyn Monroe vignette was all so wildly inappropriate. Yet no one complained or embarrassed me. In truth, my behaviour in England barely improved over time. Excerpted from Coming Ashore: A Memoir by Catherine Gildiner All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.