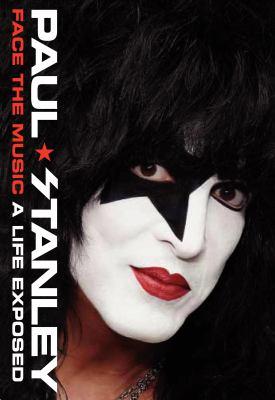

Face the music : a life exposed

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Victoria | Available |

Browse Related Items

| Subject |

| Stanley, Paul, 1952- Kiss (Musical group) Rock musicians > United States > Biography. |

| Genre |

| Autobiographies. |

- ISBN: 0062114042

- ISBN: 9780062114044

- Physical Description 462 pages

- Edition 1st ed.

- Publisher New York : HarperCollins, [2014]

- Copyright ©2014

Content descriptions

| General Note: | "Harper One." |

| Immediate Source of Acquisition Note: | LSC 35.99 |

Additional Information

BookList Review

Face the Music : A Life Exposed

Booklist

From Booklist, Copyright (c) American Library Association. Used with permission.

Most people will probably not associate sensitivity with the flamboyant heavy-metal rock band KISS, and yet in his memoir, front man, rhythm guitarist, and cofounder Paul Stanley succeeds in making a connection with the reader, KISS fan or not. Born with microtia, a deformity that left him deaf in his right ear, Stanley felt like a freak. His stage makeup (heavy white face paint with a star around his right eye), therefore, functioned as a mask that hid his doubts and insecurities and turned him into a larger-than-life persona, Starchild, which served, he explains, as a defense mechanism to cover up who I really was. Stanley discusses his childhood growing up lonely and friendless in Manhattan and Queens, and the pivotal night when he saw the Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show and realized that music would be the vehicle to lead him out of his misery. He also writes about his fellow band members, the ups-and-downs of stardom, and the decadent rock-star lifestyle, coming across through it all as likable and down-to-earth.--Sawyers, June Copyright 2014 Booklist

Kirkus Review

Face the Music : A Life Exposed

Kirkus Reviews

Copyright (c) Kirkus Reviews, used with permission.

KISS' flamboyant "Starchild" unplugs his high-wattage amps and introduces fans to an even more intriguing character: Stanley Harvey Eisen.Few who experienced the power of a KISS concert during the 1970s could have imagined that one of the preening men commanding the exploding stage in makeup and high heels was actually an anxiety-riddled loner from Queens hiding a rare facial deformity called microtia. Growing up, the condition left Stanley half deaf with a "stump of an ear" that prompted sensitive neighborhood kids to jeer him as "the monster." The axe-slinger behind some of KISS' most anthemic songs displays a laudable frankness in discussing those troubled times, made all the more trying thanks to a set of emotionally unavailable parents and a mentally disturbed sibling. The bleakness of the music-obsessed teen's existence eventually drove him to seek out his own psychotherapist. Still, the author possessed an almost uncanny certainty that music would be his life. That unconquerable drive, coupled with a deep and abiding desire to belong to something, brought him into the orbits of three decidedly disparate characters: Gene Simmons, Peter Criss and Ace Frehley. Stanley describes the halcyon days of KISS' formation as the realization of his dreamsbut there were problems from the inception. Despite a dynamic conceived as a sort of fun-house reflection of the Beatles, the KISS brotherhood, as Stanley regards it now, was always built on suspect fortifications. Those weaknesses would come to light at the end of the 1970s, after the band had already conquered the world and intra-band friction took hold. Stanley recounts the worst of itthe 1996 reunion tour that, while successful, fell woefully short of the bombastic comeback the Starchild had envisioned. None of Stanley's band mates escape his withering criticism, but Criss is clearly his favorite target. At peace with the state of KISS today, Stanley reveals that the most precious things in his life now are his sense of enlightened awareness and cooking elaborate meals with the wife and kids.An indispensable part of KISStory. Copyright Kirkus Reviews, used with permission.

Publishers Weekly Review

Face the Music : A Life Exposed

Publishers Weekly

(c) Copyright PWxyz, LLC. All rights reserved

Born with an ear deformity called microtia-a condition in which cartilage on the outer ear fails to from properly-which left him with an ugly stump on the right side of his head, Stanley, co-founder and lead singer of KISS, faced ridicule and taunts from classmates and found little sympathy or affection from his unhappy family. By the time he was 12, the Beatles blew into his world on the Ed Sullivan Show, and he discovered rock and roll; he eventually picked up a guitar, joined a band, and music eventually became his refuge. Elegantly and thoughtfully, Stanley takes us behind the mask of Starchild, his KISS persona, and shares intimately his own insecurities about his physical appearance and his emotional life. Along the way, he chronicles the meteoric rise of KISS-he and Gene Klein, who changes his last name to Simmons, just as Stanley Eisen becomes Paul Stanley, start playing in a band in high school-in the 1970s, their difficulties, and their eventual fall from fame. Throughout the glory years, Stanley remains lonely and feels like an outsider off stage. In 1998, his starring role in the Phantom of the Opera dramatically prompts Stanley to face himself: "Why had I let my birth defect keep me from sharing myself with people, from embracing people-from embracing the fullness of life?" He starts working with children with facial deformities in an organization called About Face, and here he movingly shares the lessons he's learned: "It's not about being perfect, being normal, or seeking approval; it's about being forgiving of imperfection, being generous to all sorts of people, and giving approval." (Apr.) (c) Copyright PWxyz, LLC. All rights reserved.

New York Times Review

Face the Music : A Life Exposed

New York Times

June 1, 2014

Copyright (c) The New York Times Company

ALL ROCK BIOGRAPHIES/MEMOIRS agree on one point. As Gregg Allman tells it in "One Way Out," an exhaustive oral history of the Allman Brothers Band by Alan Paul, escaping the workaday lot of "a shock-absorber washer-jammer in Detroit ... is why I became a musician in the first place." Or as Joey Ramone sang: "It's not my place in the 9-to-5 world." Whatever form the music might take, it promised a palatable alternative to the routine assembly-line life. Learn how to play an instrument, be able to clutch a mic and project some personality or attitude, and you too might ascend from the pits of menial-labor, desk-job drudgery, or the "Do you want fries with that?" service industry. Not only were shimmering nonunion perks like sex, drugs and fame on the table, but you could sleep until the afternoon, not be penalized for lapses in hygiene or deportment and, with luck, get paid to be utterly irresponsible. What wasn't to love? You didn't even have to be a musician to tap into that life. In 1969, you could be a young substitute teacher in Harlem who started working after school in the office of a syndicated music writer/D.J./would-be record producer named Richard Robinson, and in no time find yourself skating down a yellow brick road of free record albums, concert tickets and record company buffets straight into the spanking new field of rock journalism (while marrying the boss in the process, a union that would also stick). As Lisa Robinson says in her winning THERE GOES GRAVITY: A Life in Rock and Roll (Riverhead, $27.95), she wasn't like the "boys who had ambitions to become the next Norman Mailer": She took over her new husband's column and was off to the races. A dedicated Manhattan girl, she adopted a very laissez-faire, New Orleans attitude to the rock circus - let the good times roll over you and leave the existential-metaphysical-political implications to others. Robinson wasn't a partyer, though. She came for the music and the warped conviviality of the milieu (a professed "drug prude," she passed on the cocaine hors d'oeuvres). Observing Mick Jagg er or Robert Plant in their offstage habitats was almost as entertaining as seeing Keith Richards or Television's Tom Verlaine play sublime guitar licks. By the '70s, Robinson was writing a cheeky gossip/ fashion column she called "Eleganza" for Creem magazine. This led to her being hired as the press liaison for the Rolling Stones' 1975 Tour of the Americas. (Annie Leibovitz was the tour photographer.) Robinson's account of this semidebacle is full of telling vignettes, but fuzzy on the overview. The bassist Bill Wyman spent his free time obsessively videotaping old Laurel and Hardy movies, which is a perfect snapshot of his distance from his mates - the odd man already out of the band in spirit if not body. Robinson's take on Jagger's mindfulness of public opinion is less satisfactory: If the tour was intended to counter a growing perception that the Stones were creatively bankrupt, how was this bloated show - featuring a million-dollar stage rig and a truly ridiculous inflatable 15-foot penis among its props - meant to do that? She writes: "Much to my dismay but to the delight of the crowd, Mick initiated his incredibly corny shtick of hitting the stage with the belt during 'Midnight Rambler.'" Precisely. Her curious assertion that "punk was peaking" at that moment - mid-1975, just when the Sex Pistols were forming and most of her beloved CBGB bands hadn't even scored record deals - doesn't help matters either. (I'm shocked she doesn't mention the Stones' stomach-churning 1974 video for "It's Only Rock 'n' Roll," where the boys performed in wee white sailor suits while being covered in soap bubbles.) Lapses in context aside, Robinson is often delightful company. She spins good yarns and drops nifty tidbits about a litany of the great and the weird. Meet Lou Reed after hours (she and her husband videotaped him singing an early version of "Walk on the Wild Side" on their couch), kibitz with the New York Dolls' peerless David Johansen, visit Michael Jackson (spanning the whole career from boyhood to total dissolution). You can dine with a voluble Phil Spector, delve into the pontifical all-things-to-all-people contradictions of U2 and recall a certain Ms. Smith's prestardom cabaret act: "Patti wore a feather boa (yes, she did), sang Kurt Weill's 'Speak Low' and paid homage to Anna Magnani and Ava Gardner. This did not catch on." "There Goes Gravity" aims to entertain, but it also illuminates more than enough. On the subject of one group of "hairy, sweaty boys, wearing makeup and costumes," though, Robinson is virtually dumbstruck: "I was appalled that this foursome, dressed as cheap cartoon superheroes, were ripping off the music of the adored New York Dolls. Badly. Without a modicum of wit." This would be Kiss, whose chief architect and bottle washer, the guitarist and singer Paul Stanley, has written FACE THE MUSIC: A Life Exposed (HarperOne, $28.99) to Set the record straight. In all modesty, he lays bare the truth of how the former Stanley Bert Eisen, a shy Jewish boy born with one deformed and deaf ear, overcompensated by orchestrating nearly every aspect of his band's eventual success. ("I would be the Wizard of Oz: the awkward little man behind the curtain operating this huge persona.") "Face the Music" straddles the entrepreneurial (think Ray Kroc as rock Svengali) and therapeutic (it is published under an imprint whose website boasts of channeling "the full spectrum of religion, spirituality and personal growth"). The personal-actualization lingo sits awkwardly beside typically Kiss-centric statements like "Detroit became the first place we could headline a theater. I would always recall it as the first city to open its arms, and its legs, to us." So much for, um, "self-empowerment." Conquest was the band's mission, and spectacle was inevitably its main weapon: Kabuki faces and wrestling archetypes, fire-breathing indoor pyrotechnics and comic-book-meets-Penthouse-Forum misogyny all bundled into a worldview of unreconstructed (and undeconstructed) male projection. It isn't fair to say Stanley ripped off the Dolls: Kiss came about via a shrewd instinct for what was marketable and a fanatical determination to eliminate everything else (nuance, emotion, ideas) from the equation. He is actually more generous in crediting their manager, choreographer and record producers for help in forging the Kiss brand than he is with his bandmates, who are presented as unruly children in constant need of his guidance and supervision. Comparing Stanley's book with SHINING STAR: Braving the Elements of Earth, Wind & Fire (Viking, $27.95), the born-again, even more uplift-conscious memoir by the singer Philip J. Bailey, the parallels be- tween Kiss and E.W.F.'s tightly costumed and choreographed pop-funk packaging are apparent. E.W.F.'s desire to "signify universal love and spiritual enlightenment" boiled down to a New Age-y, "Boogie Wonderland" equivalent to the "Rock and Roll All Night (and Party Every Day)" gospel. The leader Maurice White had a Concept for the group that was just as theatrical and systematic: a high-gloss production that wedded mild jazz-fusion jams, falsetto flights (Bailey's specialty) and airbrushed sonorities to an ecumenical Sly Stone/Parliament-Funkadelic template. This neo-laidback vibe was achieved through guesswork (as with Kiss, more a matter of subtraction than addition) and a boot camp mentality. For all his gee-whiz enthusiasm, Bailey's "Shining Star" reveals how an open-ended, semihip aesthetic evolved into its own regimented 9-to-5 grind - with time running from p.m. to a.m. instead of the reverse. The gold records and groupies, the power struggles and Bailey's finding God are all subsumed in the show business machine; the past 25 years are covered in as many brusque pages. Even the description of E.W.F.'s induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2000 has a terse, hollow ring to it - the thrill is gone, hard as Bailey tries to put a big happy face on Life After Relevance. Performing at different times for Presidents Clinton and Obama was all swell and good, but it was as an oldies act. Like so many Hall inductees (now including Kiss), E.W.F. became their own tribute group. The story of the Allman Brothers Band is more complicated and more moving, though by the time you get through all the Skydog ups and strung-out lows, you still have a case of the Yogi Berra "déjà vu all over again" blues. Alan Paul's ONE WAY OUT: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band (St. Martin's, $29.99) is nothing fancy, but its alternating-voices format lays the band's mottled history out with a convincing sense of how its triumphs and hard times were wholly interwoven. The book's virtue is the way its democratic ethos mirrors that of the Allmans' racially integrated, communal aspect: The roadies play nearly as large a part in the story as the band members themselves. And in its 1969-71 heyday, it was a less hierarchal band than most: a very assertive rhythm section, the singer-organist-songwriter Gregg Allman's voice seldom a dominating factor, the twin lead guitars of Dickey Betts and Duane Allman serving as sonic signature to their rolling blues-jazz-psychedelic-bluegrass caravan. The death of Duane Allman in a motorcycle crash at the age of 24 (followed soon by the similar death of the bassist Berry Oakley) hangs over the band: A musical seer whose vision hadn't had time to fully coalesce, Allman was a well-read, forward-looking, self-effacing prodigy who might have guided the group down any number of avenues. Members in the meantime have come and gone, but a collective estimation of What Would Duane Have Done? prevails even as it locks them into a permanent holding pattern. It's easy to sentimentalize someone with Duane Allman's potential, but just look at what happened to Eric Clapton after the two collaborated on "Layla": plop, right through the easy-listening trap door to "Lay Down Sally" and decades of wine-in-a-box insipidity. The many perils of rock genius (in or out of scare quotes) are on full display in Holly George-Warren's poignant, invigorating a MAN CALLED DESTRUCTION: The Life and Music of Alex Chilton, From Box Tops to Big Star to Backdoor Man (Viking, $27.95). The book makes a perfect companion piece to the 2012 documentary about Chilton's hard-luck band, "Big Star: Nothing Can Hurt Me." It fleshes out the back stories, the wild personalities and the Memphis bohemian milieu where he developed, thrived and imploded: growing up in a house that doubled as an art gallery, on tour at 16 as a precocious soul singer for the Box Tops and hanging out with the Beach Boys (waking up one morning on a couch next to Charles Manson). Then Big Star, three classic albums, each a different incarnation, a different sensibility: "#1 Record," with the tortured, reclusive pop perfectionist Chris Bell; "Radio City," merging that Beatles-esque sound with Velvet Underground undertones; finally, "3rd" a.k.a. "Sister Lovers," which morphed into an ad hoc art project or exercise in Quaalude-coated chaos (what if we rewrote Lou Reed's "Berlin," but made it funny?), with the producer Jim Dickinson and the engineer John Fry playing crucial roles in pulling the whole unhinged mélange together. But everything fell apart: Chilton's relationship with Lesa Aldridge, his muse and collaborator on "3rd," at least until he erased most of her vocal parts from the master tapes, and with the record label (yet again). Hopscotching thereafter from eccentricity to eccentricity, the singer exiled himself from his legacy; as Dylan would put it, he threw it all away. Yet George-Warren's book isn't a downer. Chilton had his own brand of tenacity and perverse integrity. He found ways to keep creating intriguing, low-key music and before his death in 2010 had made some peace with the personal albatross that was Big Star. In the Memphis tradition of Dickinson and the photographer/ fellow-traveler William Eggleston, he was a weirdo to the manor born: In shambolic concert, covering Furry Lewis's "I Will Turn Your Money Green" or Benny Spellman's "Lipstick Traces (on a Cigarette)," he sounded raw, sweet and set free at last. Chilton was the ultimate cult-rock figure, but the hardy, truly hard-core Bob Dylan cultists get a book to themselves with David Kinney's fascinating, though underdeveloped, little volume THE DYLANOLOGISTS: Adventures in the Land of Bob (Simon & Schuster, $25). George-Warren's love-letter biography of Chilton ponies up far more great anecdotes and heartbreaking stories of staggering waste, but Kinney's tale of the peculiarly symbiotic triangle between Dylan obsessives, his music and the inscrutable man himself poses some interesting conundrums. In one sense, the people who follow Their Bob around on tour, scrounge his unreleased studio recordings or buy the manger he was born in are like refugees from a Coen brothers reality show: "Inside the Hoarders of Highway 61." But there is also a tantalizing sense that Dylan, as hostile or plain indifferent to them as he might appear, has his reciprocal moments too. There is a recent vignette of him visiting John Lennon's childhood home just like a Dylanite soaking up the imposing atmosphere at Hibbing High School. Kinney charts the love-hate-love pendulum Dylan's fans have with the Master's own attempts to get out from under the burden of being BOB DYLAN, poet, prophet, messiah at large. (The best way to view "Masked and Anonymous," the dystopian comedy he co-wrote and starred in about what a pain and a prison that persona is, might be as his verbose version of "Monty Python's Life of Brian.") Stuck with all those overweening expectations, it's a wonder he hasn't become another J. D. Salinger, hiding out in a walled compound in North Dakota or on an island off the coast of Scotland. Kinney's book chronicles the meandering trail of Dylan's "Never-Ending Tour" (which started in 1988 and shows no sign of ending before he dies with his boots of Spanish leather on at Little Big Horn). By excavating and reconstructing his own canon, he's succeeded in keeping it alive through an act of persistent creative destruction. He's the opposite of a custodian, the faithful Civil War re-enactor - he's the defiant imperfectionist embracing his own mortality and vocal decay, part ragged crooner, part aged illegitimate son of Charley Patton sending Daddy's ghost random notes on what's rotten in the Delta of Venus, Miss., and all points north. A curious deficiency of Kinney's book lies in his decision to take only the amateur side of the Dylanological urge into account. The serious critics and artists who have engaged Dylan with as much passion and sometimes leap-in-the-dark impetuousness as civilian monomaniacs are passed over with sparse comment. Jonathan Lethem gets acknowledged vis-à -vis his thoughts on appropriation/theft, some theological interpretations are touched on, but others are virtually banished from consideration. Sean Wilentz and Christopher Ricks are barely name-checked, and Greil Marcus's three Dylan books come up only in passing. (If nothing else, you'd think Marcus's tunnel-visionary study of "Like a Rolling Stone" might generate some amused debate for how cavalierly it accentuates the affirmative and gives Dylan's propensity for sadistic negation short shrift.) What are Todd Haynes's fan-fictionalized "I'm Not There" and Martin Scorsese's sprawling "No Direction Home" if not eminent personal acts of Dylanology? Dana Spiotta's 2006 novel "Eat the Document" could have made a nice mirror to illuminate some of the fringe figures Kinney tracks down. "The Dylanologists" seems to be rushing to the finish line when a more considered, burrowing approach would be way more gratifying. Pondering what makes Dylan so gripping and elusive, I was listening to one of the thousands of bootlegs his fans have graciously made available. "Looking for Maurice Chevalier's Passport in America" is a compilation of 2002 performances; here are a number of fond versions of Warren Zevon songs, as he was dying of cancer. This, and Dylan's terminal-case version of his own "Love Sick," made me recall something Lou Reed, as he too lay dying, told his sister, Merrill: "I don't want to be erased." The Zen of Dylan - or a Big Star fortune cookie - therefore might go: Live in the moment of your own death. Beats working for a living. HOWARD HAMPTON is the author of "Born in Flames: Termite Dreams, Dialectical Fairy Tales, and Pop Apocalypses."

Library Journal Review

Face the Music : A Life Exposed

Library Journal

(c) Copyright Library Journals LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Media Source, Inc. No redistribution permitted.

Before Stanley cofounded the rock band KISS, he was Stanley Harvey Eisen, a boy born partially deaf with a stump for an ear. Kids were unkind, and he had an unhappy childhood and unsatisfying family life. College wasn't for him, but he found his calling in writing and performing music, not letting his birth defect stop him. After working hard and hanging out with the right people, KISS became larger than life for a time, but drugs and egos interfered. -Stanley never gave up, though, and managed to keep the band alive as musicians came, went, or lost focus and as the music scene changed. This year marks the 40th anniversary of KISS's first album, and Stanley has seemingly found happiness and stability with the current lineup of members, his children, and his second wife. The author is the last of the founding KISS members to tell his story in a book, and the result, while entertaining and revealing, is bloated with analogies and euphemisms. Apparently, very few people in his life failed to disappoint him in some way, and he incessantly makes his disdain for former bandmate Peter Criss abundantly clear. Despite all the negativity, though, Stanley wishes to inspire readers to improve their lives and be happy. VERDICT Essential for the KISS Army and for fans of rock and roll tell-alls.-Samantha Gust, Niagara Univ. Lib., NY (c) Copyright 2014. Library Journals LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Media Source, Inc. No redistribution permitted.