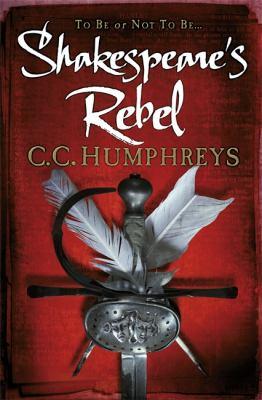

Shakespeare's rebel

In 1599 London John Lawley, England's finest swordsmen, has a complicated life. All he wants to do is be left alone to win back the love of his wife and estranged son and to help his oldest friend, Will Shakespeare, finish his latest play but orders from Queen Elizabeth to fight for the crown in Ireland threaten to interfere with his plans.

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Victoria | Available |

Browse Related Items

| Genre |

| Historical fiction. Biographical fiction. Fiction. |

- ISBN: 1409114902

- ISBN: 9781409114901

-

Physical Description

print

408 pages : map - Publisher London : Orion Books, 2013.

Content descriptions

| Bibliography, etc. Note: | Includes bibliographical references (pages 405-406). |

| Immediate Source of Acquisition Note: | LSC 24.99 |

Additional Information

Excerpt

Shakespeare's Rebel

I

The Martin Drunkard

February 1599

John Lawley lay in a ha'penny bed in the lowest tavern in Wapping, musing on fleas, on Irishmen, and on drums.

Did the fleas that feasted on him so vigorously die once they had gorged?

Had the Irishmen who had just, for the third time, stolen the whole of their shared and threadbare blanket ever slept between rich linens, as he oft had?

Also-and this was his most pressing concern-did the drum that beat so loudly exist, or did it strike only within his head?

It was important to know. For if it existed, then truly he should answer its summons. Waking, though, meant taking action; the first of which, surely impossible, the lifting of his forearm from his brow. Yet even were he to accomplish such a feat, prove himself that Hercules, what then? To what task would the drum drive him next?

Nothing less than the forcing of his gummed eyelids.

That was too much. Furies hovered beyond them. Some were even real. Rouse and he would be forced to distinguish between them. Rouse and choices would have to be made. Whither? Whom to seek? Whom to avoid?

There were too many candidates for both.

No. Even if every drum stroke, imaginary or not, beat nausea through his body until he was forced to do otherwise, it was better to just lie there and utter prayers for the beat to fade. And while he was about them, pray also that in its fading the sweats would begin to warm, not chill.

He shivered. He'd have liked his paltry share of blanket back. To reclaim it, though? That required the same effort demanded for arm, for eyes...

Impossible, he concluded. Sink back then. Seek warmth in memory. Illusion could sustain him. Indeed, in circumstances far worse even than these, illusion was all he'd had. Among all the things he was, was he not a fashioner of dreams?

Was he not a player?

He was. So make the drum real. Place it beyond, not within, his head. Make the heat real too, not the little transferred from men's rank bodies.

Where had he been hottest? Under a Spanish sun. Yet temper its fierceness with a breeze over waves. Conjure other sounds to drown the rising mutters of his bedfellows.

The plash of oars? The boatswain's call to each beat?

Thump.

"Pull!"

Thump.

"Pull!"

Thump.

"Pull!"

Truly, John Lawley thought, settling back, eyes still sealed and forearm yet lolled, this morning can wait. That other was better.

For a time, at least.

Three years earlier: Bay of Cadiz, June 30, 1596

Thump.

"Pull!"

Thump.

"Pull!"

Thump.

"Pull!"

John lowered his forearm, closing his eyes to the sun's sharp bite. He had seen enough. The beach they were making for, some three miles south of the town, was undefended. He had made landings under fire before, and it was not something he sought to repeat. If his boat was sunk, his three primed pistols would be soaked. Swimming in breastplate and helm while retaining his sword was hard, but it would be made more so by the fact that he could swim. The majority of his companions couldn't, and experience taught that they would try to use him as a raft, with every chance of drowning both themselves and him. He would be forced to kill them. And, truly, he was only there to kill Spaniards...

...on behalf of the man who spoke now. "Do you pray, Master Lawley?"

There was no need to open his eyes again. "Aye."

"You do? Yet I did not see you at the deck service before we embarked," the voice continued. "Soft! Perchance you were with the Catholics in the hold, celebrating a secret Mass? I always suspected you for a Papist."

"I was not."

"Then what were you about, while other men sought forgiveness and heaven's blessing?"

"About?" John smiled. "Good my lord, I was about the sharpening of my sword."

The bark of laughter made him open one eye. His questioner stood at the prow of the flyboat. "A soldier's reply," said the man, smiling wide. "Though I have often wished that you cared as much for your soul as you do for your steel." Separate red eyebrows, like hairy caterpillars upon white oak, joined to form a frown. "You are not devout, Master Lawley. You are not devout."

"Nay, faith, I am so." John assumed his pious expression, one he'd use when playing clerics in the playhouse. "For I most fervently believe that since God already has my soul in trust, he only asks that I do not part it from my body until he is quite ready to receive it. So I sharpen my steel and heed his commandment, both."

General laughter came at that, though several men crossed themselves. "Well, John," cried Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, "if you ward my back in what is to come as well as you have ever done, then I will undertake to pray enough for us both." He squinted up into the burning sky. "He well knows that I have worn out the knees on a dozen stockings on the voyage here, to give us His victory this day."

Not those stockings, though, thought John, eyeing them where they peeked above the boots. These were new and saved for the occasion. Tangerine, the earl's own color, and a match for the sash that girdled the shiniest of breast- and backplate, that burnished shine spread through other items of armor-vambrace upon his arms, greaves upon his shins, gorget at his throat. Beneath these, the rest was swathed in finest black cambric.

Should the Lord choose to ignore his entreaties, thought John, young Robbie will make the comeliest of corpses. Yet not only his apparel would distinguish him. The face brought aboard the ship in Plymouth, bloated with excess and worn by cares, had been transformed by four weeks of sea air and exercise into the handsomeness that so inspired the balladeers. Essex had commanded John to fence him daily, and stripped to the waist the two of them had dueled, gripped and thrown upon the quarterdeck of his vessel, the Due Repulse. If during the first fortnight John had held back, while his pupil shrugged off the life of both indulgence and ceaseless, sleep-sapping intrigue he lived at court, in the last two weeks the earl had regained both strength and many of the skills John had taught him over the years. Another week and perhaps he'd not have bested his protégé. Essex was ten years younger after all, a bare thirty, half a head taller, lithe for his height. It was a good time to be turning their skills upon a common enemy-one who would perceive them as twinned furies, with John dressed near identically to the earl, if less sumptuously, being in his hand-me-downs. It was a noted subterfuge of war to have two leaders to confuse the foe.

Yet they were not the only ones with trimmed beards, styled hair, and lean shanks. Others had joined in the training. One spoke now. "And what steel he raises for your cause and God's, my lord!" the man cried. "A hardy broadsword, note you all. None of your foreign fripperies, your 'rap-i-ère'"-he exaggerated the French sounds-"for John Lawley. A yard of English steel to carve two yards of soil for any Spanish hidalgo he meets."

Jeers came from more than one man while John smiled. His friend George Silver was a fanatic for all things native-especially the nation's traditional weaponry-and deplored the foreign blades that several of their comrades bore. In the face of their jeering, he grabbed John's arm. "Come, Master Lawley. Help me convince these fools of the virtues of true English weapons."

John reclosed his eyes and turned his face once more to the sun. "George," he drawled, "the only virtue I subscribe to is in an old proverb: 'It is good sleeping in a whole skin.'"

"Nay, John! Good my lord..." began Silver loudly, as other men entered the quarrel.

"Peace, all." The earl's voice silenced the hubbub. "And know only this: I care little how you kill our foes this day. Spit them with rapiers, hew them with backswords, smash them with staffs...or pluck me their eyes out with a three-tined fork!" He laughed. "'Tis one to me. Only so long as yon citadel of Cadiz is mine by nightfall." All men looked northwest, to the ramparts of the city. "Mine, not my effing Lord of Effingham's or, worse, that popinjay Raleigh's!"

All now looked back to the men-of-war, where the fleet's guns still smoked from the havoc they'd wreaked upon the enemy. "For my part, I know only this," the earl continued, his voice softer as he drew two inches of steel above his scabbard. "This English blade was bequeathed to me by another hero of our land. And for him and that land it shall this day be lodged in some Spanish breasts-or lodged beside me in my tomb." He shoved the weapon back. "And now, master boatman, double time if you please. Some other vessels seem eager to beat us to the beach. Impudent dogs! Do they not remember that I must be first in everything?" He waved the helmet he held above his head. "And I will begin by being first on enemy sand," adding with a roar, "Stop me if you can!"

He was echoed from his own boat and from those nearby. Theirs surged ahead, at the boatswain's speeded cry, the drummer's increased beat. Silver, flopping down again beside John, leaned in. "Ah, Lawley," he said, "you may fool some with your veteran's ennui." He mimed a yawn. "But I know different. Know that you are as ardent for glory as any man here."

"I am ardent for gold." John grunted. "And the pickings of the sack of Cadiz could be rich indeed. Now let me sleep." Closing his eyes again, he wondered if Silver was right. What were these twitchings about his heart? There was only one other place he'd had similar feelings-in a theater with a new play to give and too swiftly conned lines to speak. Yet this, of battle? It had been eight years since he'd last drawn a sword in more than playhouse anger. Different commander, same enemy: the one he'd fought near all his life and across this wide globe.

Spaniards, he thought, taking a breath. There is always something about fighting Spaniards.

A concerned cry opened his eyes. Their vessel, which had drawn initially ahead, was starting to fail. They had fewer men at oar than some of the others, carrying Essex's close companions as they did, and some of those oarsmen were flagging now. John knew that Robert needed to be first ashore, first to the gates, first through them; that he cared little about plunder though he was probably more debt-ridden than any. All he wanted was the glory-and Queen Elizabeth's hand tugging his red curls, calling him once again her "sweet Robin."

He saw the earl's shoulders droop. From their first meeting ten years before, John knew the young man to be prone to a sudden melancholy that could be brought on by just such a reverse. "To oar, lads!" he cried, seizing the one from the puffing sailor beside him. "Let we yeomen of England disdain nothing in giving our lord his first triumph."

The cry was taken up, the challenge. Essex himself dropped down to grasp oak. After an initial slip of momentum as one man replaced another, the oars dipped again, the vessel surged. They may not have been sailors, but the Bay of Cadiz was calm and the trick one they had all learned before.

The boat grounded, the man at the prow launching himself with the sudden stop. Water lapped his boot tops but did not halt him. Five strides and he was on dry sand. And for a moment, Robert Devereux, Earl Marshal of England, had sole possession of that foreign shore.

"Cry God for Her Majesty!" he shouted.

But another name was on the lips of those who spilled over gunnels to follow him.

"My lord of Essex!"

The ha'penny bed, Wapping, 1599

"Will ya stop kickin' me, varlet?" the voice said. "Me shins are already as black as a Negro's bollocks."

"Sure now, give him blow for blow," a second voice suggested before lowering to a whisper. "Or have you sought other recompense in his purse?"

John did not try to open his eyes. They were still stickily shut beneath his forearm. Besides, he wasn't disturbed by the question. He already knew the answer-the one the first man gave now.

"'Tis as barren as my da's fields these last three summers. So if he kicks me one more time, or tries again to steal back his cloak-the least he owes me, mind, for the night he's given me!-I'll pay him with that blow. You'll see."

John ceased writhing. He didn't want rousing just yet from his reverie of warmth. Especially as he had just come to the part where it had all gone so well.

Until it hadn't.

"What's he moaning about now?" the other man asked. "Is that Spanish? He's dark enough for a dago, ain't he? A pox on him if he is. I'll join you in giving the dog a beating, you can be sure."

You'll be one of a crowd, thought John, drifting back...

Cadiz, 1596

It had been too easy. The unopposed landing, the three-mile march on soft sand to the plain before the city gates. Five hundred mounted dons had attacked an advance party sent for the very purpose of luring them on, bait for a trap, duly sprung. At Essex's command, the main body had erupted from their concealment, pincering the Spanish. A volley from musket and pistol and the proudest hidalgo fled, pursued by Englishmen shrieking like fiends. The defenders had shut the gates so fast, half their number were trapped outside. Yet rather than surrender there, or, more likely, be slaughtered by the charging enemy, they had shown that enemy the swiftest way into their city-through walls under repair, scaffolding up against it and holes still full of tools.

"On! On!" screamed Essex, red-stained sword aloft and running at the widest hole, through which a cloak, emblazoned with the Star of Seville, had just disappeared. Yet even as he reached the gap, its edges exploded, mortar blasted out by shot, fragments of stone and metal whining off his breastplate and helm. To the horror of all, the earl fell, but immediately scuttled to the hole's side, joined there in moments by his closest companions.

John was among the first. "How fares my lord?" he said, reaching out to the blood that daubed the tangerine sash.

Essex glanced down. "Not mine, I think," he said, brushing aside the reaching hand. "Or if it is, it's mingled with a few others." He laughed. "God a mercy, John, that was a good first roll of die. But what's within?" He jerked his head at the hole. "Can we storm this, think you?"

John thrust his head into the gap, noted the inner wall that faced this outer one, saw flintlock flashes there, withdrew just before bullets nipped the masonry. "A wall defensible about fifty paces off and a killing ground before it," he said. "Hard to tell the numbers. Not many, I'd hazard, since they chose to relinquish this wall"-he slapped the one they sheltered behind-"to defend that. Still, enough to pin us here, for we can only go through this gap two at a time. If we wait for numbers..."

But Essex had stopped listening. "You'd hazard and so would I, Johnnie. All we need is to buy a moment." More of his advance guard were arriving, weaving to avoid the fire of snipers in the turrets. Some of these newcomers bore muskets, others grapple and rope. "Silver?"

The swordsman slid across. "My lord?"

"Take you these dozen musketeers to the scaffold above. Tell me when they are primed."

"My lord."

While he scrambled up, followed by his men, Essex took out a pistol. "Load all. When Silver calls, be ready to move."

"My...my lord, a word." The tremulous voice that came was that of the earl's steward, Gelli Meyrick. On a nod, the man continued, his Welsh tones heightened by the strain. "You have oft asked me, look you, that I counsel you when...when impatience rules your honor. Even at the risk of your displeasure"-he swallowed-"I so counsel now." He pointed back the way they'd come, across the valley dotted with the bodies of Spanish cavalrymen and riderless mounts, to the slight rise beyond where forces were mustering. "I see my lord of Effingham's standard there. He brings the main body. If we were to wait, look you..."

"Wait?" roared Essex. "Is that your counsel? Wait for my lord Charles to march up and steal my glory? I piss on him and any waiting." He finished loading the pistol, snapped its steel down, thrust it into his cross belt, began loading another. "What say you, Master Lawley?"

John looked up from his own loading and into the younger man's eyes. They were maddened within the streakings of black powder. Yet somewhere in the heart of them was also the misgiving Essex ever had. He gave every man's doubts an ear and could be swayed by them. Or woman's-a queen's slight would send him to his bedroom for a month. But John also knew this well enough: Essex would rather be dead than cede an ounce of glory to any other.

John glanced around at the other men, clutching pistols, hefting swords. While blood was up, they may as well act. First glory-if they survived-but first pickings too in a town as rich as Cadiz. His share would solve a lot of problems back home. Rich enough, it might even persuade Tess to marry him. "I am game if you are, good my lord."

"I am. Oh, I am!" Essex looked around at other expectant faces. "And you, stout hearts? Are you with us?"

"Aye," came the shout.

Pistols loaded, armor adjusted, a man, one Robert Catesby, leaned forward. "Master Lawley, I heard a strange rumor of you: that you are, as well as a famed warrior, a player of some note. Is it true? Have you strutted the platforms of England?"

Plus a few on the Continent, thought John. But it did not feel like the right moment to detail his curriculum vitae. So he simply nodded and said, "I have."

"Well, sir, in my experience of 'em-and I am particularly fond of Edward Alleyn's performances at the Rose." John rolled his eyes. "Well, sir, could you not give us some speech of fire from the repertoire. Some warrior's words to see us through the wall and among the enemy? Tamburlaine's, perhaps? Or even Our Majesty's illustrious grandfather and his words at Bosworth?"

Marlowe or Shakespeare? John thought. He had played them both, of course. He had his loyalty to the brother of his soul, William, and his preference. Yet truly, he cared little for recitation unless there was coin in it. So now he glanced at Essex, just finishing the loading of his last pistol. With his red beard stained with black powder, someone else's blood on his cheek, and a dancing light in his eye, he looked like the youth John had first met ten years before.

John leaned forward. "Nay, lads, why hearken to some false and foreign hero from the playhouse when you have a true and native one before you? And when our commander writes verse as inspiring as any?"

Essex shrugged, entirely failing to look modest. "Aye, good my lord" and "We pray you, do" rang out.

The earl looked slowly around, then nodded. "Then see here," he said, rising to one knee and drawing his sword. "This weapon that I carry is the very one carried beside me into battle ten years since by my brother in arms, the brother of my heart, Sir Philip Sidney." A sigh came. "That was a day, Master Lawley, was it not?"

It was not the hour for memory but for myth, so John simply gave the nod required, and the earl continued. "At Zutphen in the Netherlands it was, and three thousand Spaniards marching to relieve the town while I...I had but three hundred mounted Englishmen to stop them. Yet I did not hesitate. With Sir Philip on my right arm and John Lawley on my left, three times we charged, and rallied, and charged again." He paused, and his eyes filled. "Yet on that final charge, his blade becrimsoned in foemen's blood, my brother took the musket ball that gave him his quietus."

He looked around at all the faces, those nearest, those others who'd drawn nearer as he spoke, and raised his voice to reach them. "He died in my arms two weeks later. He gave me this sword ere he did, and these words: 'Never draw it without reason nor sheathe it without honor.'" He nodded. "I never have, and I never will. And I will not on this day." He focused on one man. "So do not counsel that we wait for others, Gelli Meyrick. Do not seek fellow travelers on the path to glory. They will only get in our way." He looked around the circle. "This honor, and England's glory, belongs only to us," he added, and holding the sword by the blade, he raised it up before him like a crucifix.

Men reached out and placed their hands upon it, as if it were indeed the true cross. John only hesitated a moment, remembering well where that particular path of glory had led-to Philip Sidney's tent, and the foul-sweet stench of gangrene as the poet-warrior died. Yet Essex had not only inherited the sword, he had inherited the mantle of the dead hero. Men would follow it, like a banner. Follow him.

A voice from above. "All's ready here, my lord," George Silver called.

Essex stood, lifting the sword high. "For honor! For England! For St. George!" he cried.

"Honor! England! St. George!" came the shout from two score throats.

Smiling, Essex tipped his head back and shouted up, "Fire!" He drew one of his pistols and half cocked it. John did the same, readying himself.

Above, the musketeers laid their weapons on the ramparts; a ragged volley was discharged. "Now, Goodman John?"

"Now, my lord."

Both men went to full cock. At a nod, they thrust their pistols through the hole, pulled their triggers. Then, through the gun smoke and side by side, they entered the city of Cadiz.

The two who followed them died, Spanish gunmen rising from the crouch. But more Englishmen charged through while others swung down on ropes from above. Briefly it was backswords and bucklers against rapiers and pike. Some of the enemy fought bravely. Most broke and fled down the narrow streets that gave on to the wall.

"Follow! Halloo! Halloo!" cried Essex, giving the hunter's call. Somewhere a bugle echoed him-Lord Howard, Raleigh, and the rest of the English army approaching fast. The chase was on along the path, and glory was the prize.

The ha'penny bed, Wapping, 1599

"There's something hard diggin' into me."

"I thought he was too sottish for that. Foul bastard!"

"Not in his breeches, ya simpleton. Higher up, about his chest."

"Dagger?"

"Too small. Feels like...like a locket, mayhap."

"A locket?" Fingers rasped on an unshaven jaw. "Let's have it out. Perhaps it'll fetch enough to pay us for this wretch's thrashing that so marred our sleep."

"Do you stand by with your cudgel then, though I doubt he'll stir. I'll delve. Christ's guts, but don't he stink?"

John heard the words, felt the fingers questing for the locket Tess had given him on a happier day. He should have sold it three days since, bought one last bottle of the water of life. Was her cruelty not the reason for the debauch, after all? Should she not share the cost? And yet he'd found he could not.

It would take a better picker than this oaf to pull the jewel from him. So he had some moments to linger still, where the land was warm and the cause clear.

Cadiz, 1596

They'd pushed too far, of course. Blood in their ears, its taint in their nostrils, fleeing backs, feeble stands brushed aside. They'd chased as far as the town's central square, where someone had rallied the last of the defense. Too few, too late for the English army, whose bugles were sounding even then from the town's main gate. Too many for Essex's band, down to twenty, dwindled now by casualties and those who'd slunk off to loot.

A volley of sorts. Two more of their band on the cobbles and fifty of the dons running from the ranks, screaming, "Para el rey! Por Dios! Para España!"

"Back!" shouted Essex, and it was the Englishmen's turn at quarry. Down the alleys they'd stormed up, making for the walls again, John in step with Essex, Silver and the rest speeding ahead. No one was panicked. Bugles everywhere showed that the town was fully breached and would soon be theirs. Now, if they could only keep alive till that happened.

"This is more like it, Johnnie," Essex cried, laughing as he ran. "Let's lead these dons into a hot English welcome, then turn hound and chase them back again. I want to be the one to take their general's sword." He laughed. "Though it will probably be a rapier, and Silver will mock it."

John laughed with him...until they turned into another alley, a rare straight one, short enough for the rest of the party to have cleared its end as the earl and he were entering it. Yet just as they did, from a house halfway down stepped a half-dozen swordsmen. They had been waiting for the larger party of Englishmen to run past before emerging from their shelter. Seeing only two left, with a shout they drew their weapons and advanced.

Boots on the cobbles behind. Their pursuers coming on fast, the two abreast that the alley allowed. There was but a moment to stand back to back, calculate the odds, note that they were poor, and act. "Here!" John yelled and slammed his shoulder into a door to their side. The earl joined him. Under double assault the wood splintered then gave, and they were falling into the front room of a house. A woman screamed, a child snatched up into her arms.

"There!" cried Essex, running for the doorway beyond. As their pursuers surged in, delayed by a bench John threw, the fleers took the stairs two at a time. But near the top, John slipped, a triumphant cry telling of an enemy close behind. He braced against a step, kicked back hard with both feet. Shod boots connected, and a body was falling, blocking the stairwell. The earl reached, jerked him up. Together they leaped the last few stairs.

Into the bedroom, mostly occupied by the large bed, posted in each corner and curtained. There was a window onto the street, large enough to squeeze through-but a glance showed John more dons below trying to push in. There was one other way out-a ladder rising to a shut trapdoor. "The roof!" he called.

Essex had his foot upon a rung when the first Spaniard ran into the room. But the moment he took to look around was a moment too long, John reaching him in an extended lunge, his backsword thrust straight, a slight turn of wrist guiding the Spaniard's rapier over his own shoulder while his point pierced the man's throat. He reeled back with a choked scream, dropping his weapons, hands raised to clutch and fingers failing to stem the blood that ran between them. His fall was taking him to the door, and John accelerated it, hitting him with his buckler, slamming the small round shield into the man's spine. He tumbled out, into the man who was trying to get in, and for the moment the doorway was blocked by blood, body, and scream.

John turned. The earl was only halfway up the ladder, paused there. "Go!" John yelled.

"And leave you? Nay, I'll stay."

"Then both of us will be ta'en, my lord. Let me hold them awhile and you escape." He saw the hesitancy on the younger man's face, heard the shouting on the stairs, his victim's heels thumping down 'em as he was cleared away. His comrades would be coming in moments.

He made his voice softer. "When you have made good your escape, I will yield. When we hold the town, you can have me back for a small price. But if they take the real Earl of Essex, not his substitute"-he gestured at their deliberately similar apparel-"the bargain may be harder to strike. And you would be in Lord Howard's debt forever."

The concept worked. The hesitancy vanished. Essex began to climb. "True words, Honest Yeoman," he called over his shoulder. "I will return in arms."

His boots vanished and thumped swiftly overhead. "Nay, good my lord, you are most welcome," John muttered, a brief smile coming then leaving when two dons came through the door. These were ready for him, rapiers and daggers thrust before, tips close like steel gates before bodies held well back. The brief thought came that Silver should be there, expostulating on the situation, lauding the superiority of short English blade and shield over foreign technique and fancies. It was a matter of some debate still among the fight masters of London.

Yet he was not in London but in a bedroom in Cadiz, and technique could go hang. Principle was the key with this his sole one: stay alive long enough to make good the earl's escape. Live himself afterward.

As the Spaniards came for him, he set about doing so.

In the small part of his brain that was not focused on survival, he was aware of an irony here; for in his other life, the life he preferred, the life of the playhouse, one of his tasks had been to arrange the fights that occurred in most plays. And so, like players upon a stage, he set about organizing his enemies' moves. There were more of them crowding the top of the stair and, in good conscience, two were as many as he could handle, so he was determined to hold the combat near the door and prevent entrance.

As always, he watched their weapons. For all the firmness of their guard, he could see the men's hesitancy-and that was not just because of the constant shiftings of their feet, a trait of your Spanish swordsman, forever dancing as they fought. Perhaps the sight of their comrade's body thumping down the stair, gouting blood, made them pause. Perhaps being chased like rabbits through their own town. Whatever caused it, John could use it.

And did. Raising his hilt above his head, blade angled down and diagonal across his body in true guard, he did not leave it there, but swept it in a tight circle, using only the wrist, the fastest form of attack. His weapon gathered theirs, rapiers and daggers, all four knocked aside for the moment John needed. As they stumbled sideways under the force of the heavier blade's strike, John vaulted off his front foot, spinning around, using the pivot to bring his buckler sweeping across, smashing into one opponent's cheek. With a cry he was down, sprawled across the doorway, John's whole desire.

But the other had leaped clear, regained his weapons, while the force of John's spin, the buckler strike passing to the left, his sword out right, left his belly and chest wide. The Spaniard thrust with his rapier before he could withdraw that invitation, and only a leap back, and a rapid sucking in of waist, saved his life at the cost of a button. Parrying hard with a circling flick of sword, he gave back again as the man's dagger went for his eye, deflected the swung sword over his head with his buckler. As it clanged into a bedpost, he thrust forward hard, like a pugilist punching, but the Spaniard eluded him with a slip of shoulder, then came again.

John lost every thought save two: keeping the man before the doorway and deflecting his assaults. All became a blur, blows and thrusts given, warded, redoubled. The bedposts blocked both of them, the curtains snared blades until they were shredded by slashes. In but a few moments steel met steel twenty times or more and there was not time to consider anything but that. Until John became aware of life beyond the whirling blades, of movement again at the doorway, another opponent finally stepping through it...and behind him, the creak of rungs on the ladder.

It would be typical of Essex, changeable as quicksilver, to come back. Forcing his opponent back with a whirl of blows, John risked both a look and words-though "My lor-" was as far as he got. It was a Spaniard on the ladder, he'd just flung a cudgel and John had only enough time to turn his head so it did not strike him in the face. Yet it struck his temple well enough, and his helmet only made the blow ring louder.

It did not send him entirely to oblivion, or at least not constantly. His eyesight was taken, sure, and what his other senses gave him was mixed. He heard an English bugle near, low-voiced commands, felt his body being lifted. There was street air and scents, blood in his mouth. Then a cooling breeze in the heat, salt tang, the sudden shock of his face on floorboards awash with seawater. The part of him hanging on to consciousness wondered if he was being taken back to the Due Repulse, felt gratitude at the thought. Until he heard the language the oarsmen were speaking. He understood few words of it, knew only that it was Spanish.

"En nombre de Dios," he muttered.

The ha'penny bed, Wapping, 1599

"What's the dago bastard sayin' now?"

Enough, thought John. Further in memory and I will have too much of heat. It may be as cold as a nun's tit in this Wapping tavern, but I would not trade it now to be warmed again beside the Inquisition's fires.

Besides, he could sleep no more-not when delving fingers had finally fastened on the locket. It was all he had left and he might still need to pawn it, though he'd rather keep it as a token of woman's faithlessness. Either way he was buggered if he was going to let some amateur cutpurse have it.

His eyes were still hard to open. When he finally managed it, he saw, silhouetted against the wooden slats of the tavern's attic, the same object that had lately entered his reverie-a cudgel. Its wielder was not looking at his face but at his companion's hand and what was emerging from within John's doublet.

"Bloody thing's on a chain," the thief was saying. "Can't...pry it...loose..."

"Snatch the bloody thing off!"

John wanted to say, "Can I help?" But his throat was as gummed as his eyes and issued only a groan. It was enough to make the cudgel wielder look up, see his eyes were open, pull back the club to strike...

Which took too long. John shot one hand up, grabbing the wrist, twisting, causing pain and the dropping of the weapon. His other hand wrapped around the thief's head and he pulled the man's face hard into his chest.

He had them both-but he could not hold them long. The cudgel man was large and the cutpurse wiry, and both were jerking like hogs on a rope. Releasing them by flinging them back, John rose unsteadily from the three-man mattress. At once his head spun in concert with his stomach and he had to lean down, hands on his knees, taking breath.

It gave the other men time to recover their courage, and the one his club. "Right, you whoreson," he declared, "give us that locket."

"You cannot have that," replied John, swallowing back his nausea, slowly rising, reaching up, back. "But you can have this."

There was only one other thing he possessed now, truly the last thing he would ever part with. It rested between his shoulder blades, in a sheath designed for the purpose. Drawing the six-inch blade now, he took guard.

Its appearance punctured the men's bravado like its point would have an inflated bladder-to John's considerable relief, since both men, though stationary, refused to stay still to his sight, and moreover had each acquired a glowing yellow and green carapace. "Now, now," said the wiry one, swallowing, "there's no need for that."

"Is there not?" asked John. It was a real question; yet before either man could answer, boots sounded upon the stairs. Keeping the knife before him, John shifted it slightly toward the attic door. Spaniards might be about to burst through it.

They didn't, but the landlord of the Cross Keys did. "Out, swine," the three-bellied man bellowed. "'Tis past nine. Do you think I keep a bawdy house and you the earls of March? The nightmen want your bed."

He seemed oblivious to knife or cudgel, just shooed them while a boy entered, swept a filthy cloth over the more soiled of the floorboards, and left bearing the teeming bucket. The two thieves followed with a few brave mutters and dark looks at John. Fumbling his knife back into its sheath-he nicked himself doing it, adding a future scar to the ones already there-John bent, repossessed his cloak, and lurched toward the stairs.

The landlord delayed him with words. "Someone looking for you. In the yard."

"Me?" It was a surprise. He didn't know anyone in Wapping, an outlying district far from his usual haunts. It was why he had chosen it for the climax of his month-long debauch. "Who?"

"A boy." The man put a hand on his shoulder and pushed. "Now be off."

A boy? For a moment, John's heart lurched. Ned, he thought. His first two steps were quick at the happy thought, slowing thereafter. He might want to see his son. He did not want his son to see him. Not like this, the way he looked, the way he stank. It had been a year since the last drunk, and he'd given Ned some cause for hope that it would not be repeated.

Still, he peeped into the yard, hoping to at least get a glimpse of the heir to all his nothing, ready to run out the front once he had. It was not Ned there, though, but a dark-haired younger lad, maybe ten years of age. John did not know him, though he thought perhaps he had seen him somewhere before.

"You seek me?" he said, crossing the slick cobbles with as even a gait as he could manage, making for the butt of rainwater in the yard's corner. It had a crust of ice on it. John broke it; then, taking a breath, he plunged his whole head in, gasped at the shock and pain, plunged deeper.

He stayed submerged as long as he could stand. When he rose, he discovered the boy had come closer but not close. "Well," he asked through dripping water, "who sent you?"

The boy did not reply. Perhaps he did not wish to open his mouth. Instead, he held out a scrap of paper. The moment John took it, its deliverer turned on his heel and fled.

Some of the ink smudged under what ran from his fingers. But the brief message was clear enough. He scratched at his wild beard and beneath his doublet. He was flea food again.

John sucked sour rainwater from his mustache. What did London's most famous actor want with him now?

Excerpted from Shakespeare's Rebel by C. C. Humphreys All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.