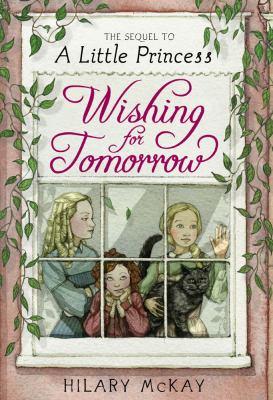

Wishing for tomorrow : the sequel to A little princess

Relates what becomes of Ermengarde and the other girls left behind at Miss Minchin's School after Sara Crewe leaves to live with her guardian, the Indian gentleman.

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Community Centre | Available |

Browse Related Items

| Genre |

| Historical fiction. Fiction. |

- ISBN: 9781442401693

- ISBN: 1442401699

- Physical Description 273 pages : illustrations

- Publisher New York : Margaret K. McElderry Books, 2010.

- Copyright ©2009

Content descriptions

| General Note: | Originally published: Great Britain : Hodder Children's Books, 2009. Sequel to: A little princess. |

| Immediate Source of Acquisition Note: | LSC 22.94 |

Additional Information

Wishing for Tomorrow : The Sequel to a Little Princess

Click an element below to view details:

Excerpt

Wishing for Tomorrow : The Sequel to a Little Princess

CHAPTER ONE Once Upon a Time ONCE UPON A TIME THERE WAS A CITY. In the city there was a square. In the square there was a house. It belonged to two sisters, Miss Maria Minchin and Miss Amelia Minchin. From the street the house looked very much like all the other houses in the square. Tall and narrow and respectable, with servants in the basement, faces at the windows, and sparrows on the roof. If anything made it a little different from its neighbors, it was the faces at the windows. There were so many of them, and they looked out so often, and they were all girls. The house was a school, a boarding school for girls. There were little ones, bouncing up to wave to anybody passing in the road below. There were big ones, telling secrets and using the windowpane reflections to admire their hair. (Mirrors were very rare in the Miss Minchins' house, and the few that existed had such thick, cheap glass that even the prettiest, healthiest people looked like they had been recently drowned in green water.) And as well as the little girls and the big girls there was Ermengarde, who was too shy to wave, and never told secrets or admired her reflection (having been brought up to believe she was plain). Ermengarde gazed out of the windows more than anyone, and her eyes were always wide and expectant, as if she was waiting for the answer to a question, or the end of a story. Often she took no part in the gossiping, whispering, schoolroom world around her. Sometimes she didn't even listen. Eight-year-old Lottie always listened. Lottie was officially a little one, but it was the school's older students who interested her most. Lavinia, for instance, an unpredictable girl with a sharp and lovely face, and a way of glancing through half-closed eyes that even her best friend Jessica found slightly scary. Lavinia was the most interesting girl in the school, decided Lottie. Jessica was the prettiest. Gertrude was the rudest. Ermengarde... "Ermengarde is a nonentity," said Lavinia. "She is a plod," agreed Jessica, and it was true that Ermengarde did not shine at anything, not lessons, nor games, nor jokes, nor stories round the fire. She had one skill, however: She was very quick and deft at freeing insects that were trapped against the glass. "Once there was a butterfly," said Lottie. "But it is usually just bluebottles..." "Disgusting things," said Lavinia. "...or wasps." "I'm sure you're supposed to kill wasps," said Jessie. Ermengarde never took any notice of these remarks. It was something she loved to do, to release the desperate buzzing into an airy silence. She would have released all the faces at the windows too, if she could, even including the stinging Lavinia. Ermengarde did not think the Miss Minchins' house was a good place to be. The house was full of whispers. The whispers were part of the pattern of the house, like the peculiar musty smell from the basement (part dinner, part dampness), the tick of the enormous grandfather clock in the hall, the night-lights that burned in their saucers of water, and the scratchings and squabblings of the sparrows on the roof. Often the whispers came from behind the curtains, sometimes several voices, fluttering and chattering. Diamond mines! Her French is perfect! I guessed that Becky was under the table! Once (at a high window without curtains) it was just one voice, very quietly: My papa is dead. Sara's voice. Whatever else Ermengarde heard or did not hear, she always noticed Sara's voice. She and Sara were best friends. Best friends even though one was a servant in the attic and the other was a schoolgirl. Even though one was pink with firelight and dinners, and the other was white with neglect. Even (most remarkably of all, thought Ermengarde) though one had a mind as bright as a flame and the other had a head that hurt at the sight of a lesson book. Thank goodness lessons were over for the day, thought Ermengarde, and she leaned her hot forehead against the cold windowpane and sighed such an enormous huffing sigh that Lavinia and Jessica looked up and giggled, and Lottie noticed her for the first time that evening. "Aren't you doing anything, Ermengarde?" she demanded. "Play with me. Play the story game!" "Oh, Lottie!" groaned Ermengarde, because of all games, the story game, which required brains and concentration and sudden good ideas, was the one that she liked least of all. "I'll begin," said Lottie, who was used to groaning, and ignored it. "Once upon a time there was...there was...go on, say the next bit, Ermengarde!" "I don't know. A tree?" "No!" protested Lottie. "A bird?" "No!" shouted Lottie, wriggling with exasperation. "A girl?" "Yes, all right, a girl will do. Once upon a time there was a girl. Called Lottie. Like me." "Just like you?" asked Ermengarde cautiously, wondering what awful traps this story might hold if the heroine was exactly like Lottie. "Yes, like me. But older. Nine." "Well then, a girl called Lottie," said Ermengarde. "Only nine, not eight, and she had...she had...she had blue eyes and a lot...a great many..." "Rabbits?" suggested Lottie, who had always longed for rabbits. "Yes, rabbits," agreed Ermengarde. "A hundred." "A hundred?" exclaimed Lottie. "A hundred! Ermengarde! Oh, all right, a hundred! Good!" "And she named each one with a secret name," said Ermengarde, "and...and...I can't think of anything else just now, Lottie." Jessica, who had been listening, took up the story. "She named each one with a secret name and she wrote the names down..." "Perfectly spelt...," interrupted Lavinia. "Yes, perfectly spelt," agreed Jessica. "On a very large sheet of paper..." "Silently," said Lavinia. "Don't forget that! She asked no silly questions. She just wrote. In beautiful writing. Silently." "Absolutely silently," said Jessica. "And she ruled the paper first, so as to keep the names straight. It took her hours. Hours and hours and hours..." "I'm not!" roared Lottie. "I'm not doing it! A hundred! I'm just not! Stop laughing, Jess, you pig! Ermie, say something!" "It wasn't now," pointed out Ermengarde. "It was when she was nine. You said so yourself. Ages away." "I suppose," said Lottie, calming down a bit. "Almost a year," continued Ermengarde. "Anything might happen in that time." "Might it?" "Anything," said Ermengarde. Ermengarde's usual state of mind was a rather dismal mixture of lessons and worries and lonely boredom. But sometimes she surprised herself. Sometimes, very rarely, there would come a friendly, hopeful glimpse of brightness, like the momentary pause of a butterfly, freed from a window, preparing to fly. Text copyright (c) 2009 by Hilary McKay CHAPTER TWO Anything Might Happen "ANYTHING MIGHT HAPPEN," ERMENGARDE HAD TOLD Lottie the evening before. The happenings began the following day, after darkness had fallen, in the attic. It was nighttime, and because it was November it was very cold. Ermengarde was supposed to be in bed, but the attic was the only place where she and Sara could meet in safety. Not that Ermengarde ever felt very safe, tiptoeing the dark corridors and staircases to the top of the house. There were deep curtained windows to be got past, and sudden draughts that shook her candle flame. She always gave a huge sigh of relief when she reached the top of the last flight of stairs and the two remote rooms given to Sara and Becky, the forlorn little scullery maid. "It's not fair to treat you the same as Becky," Ermengarde had said once to Sara. " You're not a scullery maid." "Scullery maids are people too, you know," Sara had replied, her green eyes bright with anger, and Ermengarde had hastened to add, "I didn't mean that how it sounded! I don't think Miss Minchin is fair to Becky, either. I should like her to have a comfortable room, and warm things to wear. You know I would, Sara!" "I know," agreed Sara. "I'm sorry, Ermie. I shouldn't have snapped at you like that. I know you would help Becky if you could." "And I was right about the other thing," said Ermengarde. "You're not a scullery maid! And you couldn't be, never, whatever they did to you!" "I am almost," said Sara. "I run errands for Cook, and scrub vegetables with Becky when I am not helping to teach the little ones. I do so many things, Ermie, that sometimes I don't know what I am!" "You're Sara," said Ermengarde loyally. "Just like you always were, but in a different place." It was as different a place as either of them could ever have imagined, long ago, when they first met. Then Sara had been the richest pupil in the school, so special that she had been treated like a little princess. "Not by me!" said Lavinia, which was not quite true. Lavinia had indulged in some very unkind curtsies, and had made tiara-sharp comments, too, from time to time. But Lavinia was unusual. Most of the pupils of the Select Seminary were entranced by Sara. She was kind, and good company, as well as immensely wealthy. What was more, it was a glamorous kind of wealthiness. It came from India, that fabulous land of tigers and temples. "And diamonds," said Jessica. There was great excitement when news came to the school that Sara's father had decided to invest his fortune in diamond mines. It was almost more than poor Lavinia could bear. "Let us hope they are full of diamonds then!" she had commented bitterly. "Unless he and Sara are particularly fond of very deep holes in the ground." Nobody took much notice of this remark. No one at Miss Minchin's, not even Miss Minchin herself, could imagine a diamond mine that was not full of diamonds. They were all dreadfully shocked when the fortune was lost, and Sara's father died, and Sara herself was discovered to own nothing except (as Lavinia had once rather hoped) some very deep (empty) holes in the ground. "It can't be true!" Ermengarde had wailed, but it was true and Sara had disappeared into another world. She had left her school friends and begun a remote new life, working all day and spending her nights in a bare little room high up under the tiles. Then for a while her friendship with Ermengarde had seemed to end. End? Ermengarde had wondered. No! It couldn't end! When Ermengarde was only seven years old, she had bravely approached Sara and asked if they could be friends. When Sara moved to the attic, she had been forced to be brave for a second time, and to make friends all over again. That was how she came to know the secret world where Sara lived, with Becky in the room next door, and the sparrows on the roof for company. "I like the sparrows," Ermengarde said once. "But this attic is a strange place, Sara. There are so many shadows, and it is terribly close to the sky. I get dizzy looking up. I feel like I might suddenly whoosh out of the skylight." They had laughed together then and climbed onto Sara's old wooden table to watch the sunset and feed crumbs to the sparrows, and they had been happy. "Who would have thought," asked Ermengarde, "that this attic was really so nice?" "Yes, who would have thought?" agreed Sara, and Ermengarde smiled with relief. It was so easy to say the wrong thing sometimes, and so hard to say the right. After that she and Sara pretended to each other that the attic was a perfectly pleasant place to be. They pretended it until the November night of Ermengarde's visit, and then they suddenly found they could not pretend anymore. Text copyright (c) 2009 by Hilary McKay CHAPTER THREE Daily Bread THIS IS DREADFUL! THOUGHT ERMENGARDE. DREADFUL! Miss Minchin had been scolding. Becky was sobbing in the room next door, and worst of all, she had just discovered that Sara, Princess Sara, Sara whom no rags nor hard work could turn into a scullery maid, Sara her dear friend, was hungry. Not hungry in the way that you become during the Sunday sermon in church, wondering which pudding will follow the roast beef. Nor the sudden emptiness caused by the smell of a warm baker's shop on a cold morning. A different, awful kind of hunger. If Ermengarde had ever before met someone who felt like that, she had not known. It was such an awful shock that for a minute or two she could not think. And then all at once she realized that there was something she could do. "Something splendid!" she exclaimed, and her face was suddenly so bright and awake that she did not look like the usual Ermengarde at all. That morning she had received a hamper, sent by her aunt Eliza. It was a hamper stuffed to bursting with wonderful things to eat. As soon as she remembered the hamper, Ermengarde had no thought of waiting. It must be fetched at once, she decided. Becky was crying, and Sara was faint with hunger. They need it now, thought Ermengarde, as (quaking with nervousness) she tiptoed downstairs. A few minutes later, laden and triumphant, she returned to her friends. "I'll tell you what, Sara," she said, inspired by a sudden and brilliant thought. "Pretend you are a princess again and this is a royal feast." It had been a miserable hungry day for Becky and Sara, and a miserable lonely one for Ermengarde. No feast was ever more needed, nor more gladly given. "It will be a banquet!" said Sara. It was a very well-supplied banquet. The hamper that Ermengarde had carried up to the attic was meant to last her for weeks. " Wonderful Aunt Eliza!" Ermengarde rejoiced as she unpacked sweets and oranges and figs, currant wine, chocolate, jam tarts, and little pies. And cherry cake. They began with cherry cake. They each had a slice in their hands when they heard the footsteps on the stairs. Ermengarde began to tremble. Footsteps on the attic stairs, a heavy bang on the attic door, and the hard voice of Miss Minchin, headmistress of the school, destroyer of banquets, tormenter of little girls, tyrant of servants, victim of nightmares and rages and terrible pains in the side of her head. "So Lavinia was telling the truth," said Miss Minchin, and all the rose-colored magic vanished into grayness. Becky was slapped and sent to bed in disgrace. Sara was condemned to a day without food. The banquet was seized. Ermengarde was marched away, scolded until she wept, and shut in her room. "Say your prayers!" ordered Miss Minchin when she left her alone at last. For a long time Ermengarde sat huddled on her bed, her tears all gone, her thoughts all with her friends. She tried to say her prayers but got stuck on the line, "Give us this day our daily bread." "Give them their daily bread," she prayed. "Sara and Becky. And give them lots with butter and give them dinners and puddings and milk. And if you do I will forgive Miss Minchin the trespass she did against me... "...I suppose," said Ermengarde very begrudgingly. "For thine is the kingdom," she continued, tactfully skipping the part about being delivered from evil, which plainly had not happened. "The power and the glory...Haven't you seen how thin Sara has got? You look, next time she feeds the sparrows." She crawled into bed and pulled her red shawl tightly around herself. "For ever and ever," she murmured, yawning. "That sounds like a story...." And then she was asleep. Text copyright (c) 2009 by Hilary McKay Excerpted from Wishing for Tomorrow by Hilary McKay All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.