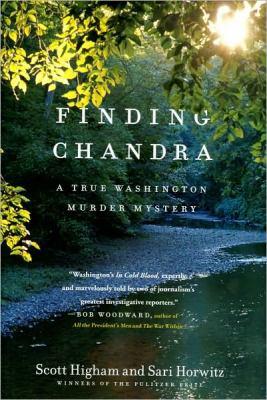

Finding Chandra : a true Washington murder mystery

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Community Centre | Available |

Browse Related Items

- ISBN: 1439138672

- ISBN: 9781439138670

-

Physical Description

print

xi, 287 pages : illustrations, map - Edition 1st Scribner hardcover ed.

- Publisher New York ; Toronto : Scribner, [2010]

- Copyright ©2010

Content descriptions

| Bibliography, etc. Note: | Includes bibliographical references (pages 249-270) and index. |

| Immediate Source of Acquisition Note: | LSC 34.00 |

Additional Information

Finding Chandra : A True Washington Murder Mystery

Click an element below to view details:

Excerpt

Finding Chandra : A True Washington Murder Mystery

1 The Bone Collector On the slope of a steep ravine, deep in the woods of Washington's Rock Creek Park, Philip Palmer spotted an out-of-place object resting on the forest floor. He saw a patch of white, bleached out and barely visible through a thin layer of leaves. Walking these woods was a ritual for Palmer, an attempt to flee the madness of the city. Each morning, the furniture maker tried to lose himself in the nine-mile-long oasis of forests, fields, and streams twice the size of New York's Central Park that slices through the center of the nation's capital. On this morning, May 22, 2002, the sun filtered through the leaves of the poplar and oak trees shading the hillside off the Western Ridge Trail, a solitary lane that begins near a centuries-old stone mill and winds its way north through the woods to the border of Maryland. Palmer moved closer to the object, his dog Paco by his side. The object, the size of a silver dollar, stood out against the leaves. Palmer's quest seemed unusual for a man of forty-two who was raised in Chevy Chase, a neighborhood largely reserved for Washington's upper middle class on the northern edge of Rock Creek Park. Thin and wiry, with a mustache, beard, and an earring in his left ear, he looked like someone who belonged in the wilderness of the Colorado Rocky Mountains. He preferred the solace of the park to the bustle and affluence that surrounded him, and he prided himself on knowing every trail and path and glen. As a boy, he would head alone to the woods after school, sift through the dirt and leaves, and look for bits and pieces of animal bones. On good days, he'd find a complete skeleton, a mouse or a rat, a vole, maybe a raccoon, prizes he would keep and cherish. The finest examples of his collection from forgotten places in the park would later be carefully displayed on the shelves that lined the sitting parlor of his Victorian home in one of Washington's trendier neighborhoods, Dupont Circle. By the spring of 2002, the park had become even more of a refuge for Palmer. Eight months earlier, on September 11, Washington watched as acrid smoke billowed from the Pentagon across the Potomac River. People in the streets looked skyward for the last of the four hijacked planes still trying to reach its Washington target. Rumors coursed through the city. The White House was next, maybe the U.S. Capitol. Since that day, the city had been under siege, awash in fear, prompted by security barricades, color-coded warnings, and police carrying automatic weapons. Congress rushed to create the biggest federal bureaucracy since World War II, the Department of Homeland Security. The nation prepared for war in the Middle East. Washington braced for a second wave of terror: a dirty bomb, another anthrax mailing, a suicide attacker on the National Mall or in the tunnels of the Metro that carried hundreds of thousands to work every day. All that seemed a world away beneath the dark green canopy of Rock Creek Park. At the northern end of the park was a popular stable, its horses carrying riders along broad, leafy bridle paths. During the day, visitors picnicked in meadows and on tables perched along the creek. At night, children gazed at the stars near the only planetarium in the national park system. Founded in 1890, Rock Creek Park consists of 2,800 acres and is the country's oldest natural urban park. The heart of the park, the original "pleasure ground" approved by Congress, is where Palmer spotted the object, between the National Zoo and the border of Maryland. The park also includes Fort Stevens, the site of the lone Confederate attack on Washington. By the turn of the century, the park on the edge of the growing capital provided a cooling respite for city dwellers. They would ride in horse-drawn carriages, and relax on giant boulders in the middle of the creek. President Theodore Roosevelt took long walks in Rock Creek Park. The park remained a pleasure ground, but over the years it had come to symbolize something else. Like many other urban parks, it had become the geographic dividing line of a racially polarized city with its vast wealth, abject poverty, corrupt and incompetent local governance, and some of the most abysmal crime statistics in the nation. On the west side were the city's well-to-do, middle-class, and mostly white neighborhoods--the stately foreign embassies along Massachusetts Avenue, the mansions of Georgetown, the soaring Gothic arches of the Washington National Cathedral, and the exclusive enclave of Cleveland Park with its Victorian homes and wraparound porches. "West of the Park" had become a euphemism for good schools and safe streets. Southeast of the park were the city's museums and Capitol Hill, but some of the neighborhoods were home to the city's most impoverished residents. Not far from where Palmer spotted the object, the cityscape began to change, the street scene growing edgier with each passing block. The transformation started east of Eighteenth Street, a thoroughfare lined with Cuban, Salvadoran, and Ethiopian restaurants and popular nightclubs in a section of the city known as Adams Morgan. Farther east were the largely Latino and African-American neighborhoods of Mount Pleasant, Columbia Heights, and Shaw, the city's nearly all-black public schools, and the dilapidated housing projects of northeast and southeast Washington, where guns and drugs claimed hundreds of lives each year, many of them young black men. Dupont Circle, where Palmer lived, was a southern gateway to the park. The three-story, turreted brownstone built in 1892 that he shared with his wife, a Washington defense lawyer, stood out among the rows of more traditional homes. Deer antlers and a large peace symbol adorned the faÃade. To earn a living, Palmer built and restored furniture in his workshop. He didn't watch television and he refused to take photographs. He wanted to live in the moment, and photographs, he thought, tarnished memories because they could only capture what things looked like, not the smells or sounds or sensations that made them whole. He had a simple philosophy--"We're like animals, we come and go"--and he was childlike in his wonder and fascination with the outdoors. "You never know what you're going to find," he liked to say. May 22 was one of those mornings that would prove him right. At about 9 A.M., Palmer parked his truck at the top of a hill near the horse corral of Rock Creek Park. He decided to walk near the Western Ridge Trail, which he hadn't been on for nearly five years. He noticed with disgust several beer bottles amid the thorny vines, patches of poison ivy, and mountain laurel that covered the forest floor. As he and Paco trudged farther into the woods, off the trail and down the ravine, he spotted a piece of red clothing. He kept walking and a few moments later came to a shallow depression in the ground. The remote spot was less than one hundred yards down the steep hillside from the top of the trail. He could hear the cars along Broad Branch Road another hundred yards below him. At first Palmer thought that the bleached-out object he spotted was a turtle shell beneath the leaves. He bent down and swept the leaves aside. Then he abruptly stood up and backed away. He marked the spot with Paco's blue leash, and his dog bounded after him as he scrambled down the hillside toward Broad Branch Road. At the bottom, Palmer hung his sweatshirt over another branch so he could find his way back up. He crossed the creek bed, clambered up the other side, and went to the first house he saw. He knocked on the door. No answer. He went next door to a house that was being renovated and asked a construction worker if he could borrow his phone to call 911. As Palmer waited for the police, his mind raced, the tranquility of the morning shattered by what he had seen: molars, missing front teeth, dental fillings, a human skull. © 2010 Scott Higham Excerpted from Finding Chandra: A True Washington Murder Mystery by Scott Higham, Sari Horwitz All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.