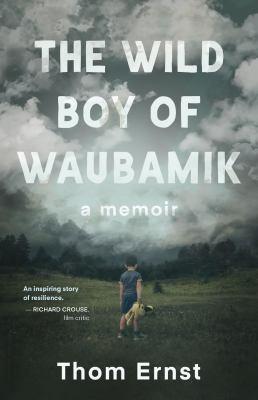

The wild boy of Waubamik : a memoir

The residents of Waubamik know about the Wild Boy, a somewhat feral child, standing nearly naked in a rusty playground of weeds and discarded metal, clutching a headless doll. They know the boy has been plucked from poverty and resettled into a middle-class family. But they don't know that something worse awaits him there. This is the story of a system that failed, a community that looked the other way, and a family that kept silent. It is also a record of the popular culture of the 1960s -- a powerful set of myths that kept a boy comforted. But ultimately, The Wild Boy of Waubamik is a story of triumph, of a man who grew up to become a film critic and broadcaster despite his abusive childhood. It reminds us that life, even at its darkest, can surprise us with moments of joy and hope and dreams for the future.

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Community Centre | Available |

Browse Related Items

- ISBN: 9781459750876

- Physical Description 234 pages ; 22 cm

- Publisher [Place of publication not identified] : [publisher not identified], 2023.

Additional Information