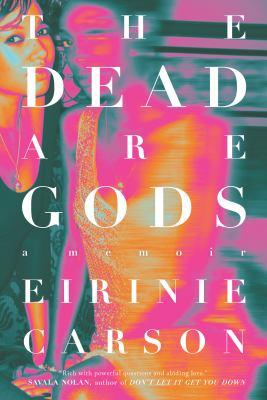

The dead are gods : a memoir

In this striking, intimate, and profoundly moving depiction of life after sudden loss, the author, after losing her best friend Larissa, attempts to make sense of the events leading up to her death, alongside a timely, honest, and personal exploration of Black love and Black life.

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Community Centre | Available |

Browse Related Items

- ISBN: 9781685890452 (hardcover)

- Physical Description 232 pages ; 23 cm

- Copyright ©2022.

Additional Information

The Dead Are Gods

Click an element below to view details:

Excerpt

The Dead Are Gods

An Introduction My best friend, Larissa, died three years ago. A sudden death, improbable and unexpected. She died a week after my thirty-first birthday, two weeks after her thirty-second. A vibrant human, also improbable and unexpected: a cool rock and roll type with a love of poetry. An enigma, hard to gain a grip on, a mythical woman, indulgent, reverent. Loved by us all. But this is not a eulogy. This is not a chapter to describe to you her love of Charlie Parker and Rimbaud and also, somehow, Gilmore Girls. Her deep love of Slipknot and wrestling but also of Baudelaire and good wine. Not a chapter to try to show you, dear stranger, the true person you have lost without even knowing you had her. But, how do we discuss grief without eulogising the people we have lost? Roughly 3.5 million people died in 2021 in the United States alone. Think of that. Think of the mothers and fathers, friends, sponsors, colleagues affected by those deaths. Think of the ripple effect from each one. We are all in mourning, all of us, but ironically, the grief feels so personal, so lonely. If someone you knew and loved has died, you know the echoing sentiments of it all too well. You know the platitudes your friends and family and (if you are lucky) therapists tell you--grief comes in waves, the only way out is through, you have to be strong for your family/their family/yourself, time heals, you must keep busy. All impossible to soak in and even more impossible to imagine implementing. You know the obsessiveness--weeks spent poring over the minutiae of the days and hours prior to death, as if somewhere, hidden in plain sight, is the answer. Something you missed that could have prevented it all. For me, it was cross-examining our texts, searching for an arrow that would say, "Look, here is her looming death. Here it is." Dissecting past conversations with mutual friends, searching for anything that would make us understand that it was unavoidable. It is a funny instinct. Why would we want proof that we could not save our loves? Why would we want to feel powerless? Perhaps only to quieten the thoughts that we could have done something, to prove that this was inevitable, that they could not be helped. Larissa died in the bath. An accident, we were told. The week she died (although at the time we only thought her missing), my toddler had put my husband's phone in her bath in the split second I turned my back whilst I went to fetch her towels. That week was also the one in which I experienced terrible vertigo for the first time, in which I said to my husband "I'm not exaggerating when I say I might be dying." I also suddenly desired to listen to 1940s jazz, Thelonious Monk, Dizzy Gillespie, and Bud Powell, some of Larry's favourites. All of these things are now, in hindsight, signs. Signs she was dead. The pain of grief is staggering. The sheer depths of it unfathomable. A tightening in the chest, an inescapable flood of sadness, the sudden need to sit up and cry. All-consuming, this pain. True, there are instances in which people claim to be fine, to be processing it all well. You yourself may be thinking, "I haven't cried once since X died and I went back to work the following day." Well, let me be your harbinger. Let me stand over you and tell you it is coming. It is un-outrun-able, we cannot be strong against it. It is a tsunami, ready to plow through your life with impunity. Maybe not for months and maybe not for years but it will be here. Doesn't that sound terrifying? Well, I am also here to tell you that to allow yourself to feel it, to stand in its dark waters, to feel the wet and cold seeping through your clothes is to weather the storm. Because when it passes (which it will, it comes in waves, remember?), clarity will come in its place. A calmness, an acceptance. The ability to recall details of your person. The way she laughed perhaps, or stood close and asked, "Are we best friends?" even though she knew the answer. Nothing has been permanent in these short (but somehow long, how does that work?) months. No feeling, no sentiment. Only her absence, I suppose. We cannot sidestep this pain, only weather it, like love, like life, like it all. I continue to grieve, and will forever, for as long as I can remember her. Time won't heal it completely but it will dull the edges of my grief, sharp and jagged and lethal as they are now. For that is what remembrance is--grieving but with the added caveat of acceptance. Hold Death close. Feel the pain and the nuances of your sadness. Remember those you loved. Say their names and tell their stories. Her name was Larissa. The only way out is through. Chapter 1 The Day After A blur. Not just one of those things you say, but really, truly, a blur. My eyes cannot focus on the plate of food Adam pushes towards me, I cannot remember getting dressed but somehow I am. My child tugs me down to the floor to play with her trains and there is some peace in that--clicking the little wooden tracks together, slotting them in place, making sure they bend and turn back towards each other, making a circle. Magnetic trains one after another, tiny hands at my aid. My phone rings and I am back, back to that gnawing at my chest, back to the dropping of my heart. I pick it up, yet another person urging me to confirm what I can barely look at. I am outside now, sitting on the steps of our LA house looking out onto the front yard. The artichokes, their jagged edges, the green, my mind drifting to harvesting them for dinner, but I suddenly can't remember how to cook them. Back to the voice at the end of the line, they are crying and it makes my tears dry instantly. I listen to them objectively, thinking how sad they sound, how distraught. I enjoy it. I am horrified that I enjoy it. That I like hearing this. Later I will reflect, realise that it was enjoyable to hear someone else in the throes of grief, confirming the worst. It was life-affirming to me at that moment, but at that moment I cannot clearly see this so I vacillate between the joy at their racked sobs and disgust at myself that I can bathe so deeply in someone else's misery. I find this so addictive that at the end of this call I find myself making another one, and another. I enjoy breaking the news to people, I enjoy hearing their pause, their contention with whether this is fact or fiction, I enjoy being told "I am so sorry, Eirinie." I want them to be sorry, I want them to pity me because I pity me and I know no other way to be right now. The sun is setting and Adam comes to tell me there is food inside, if I like. He reassures me he will do our child's bedtime routine; he wants me to know I can have all the time in the world. Do I want to run, he asks? A walk maybe? I cannot even muster the strength to tell him how tired I am, how I couldn't run even if I wanted to and I do want to, I want to run far and long until my chest aches from something other than sadness, until my legs no longer move from something other than a paralyzing sorrow, until my head is clear and all I can hear is my own breath, in and out, in and out. But I don't. I push past him, back inside. I can't remember if I have answered him but as I fall back into bed I think, let this be my answer. I sleep for an hour and when I awake the toddler is asleep, Adam is timid in his question and he seems to be unable to stop himself from asking, "Are you all right?" "Can I have some wine?" I say, and he is up and pouring a glass immediately, grateful to help. He knew her too, I think to myself. He knew her well. She was there when we met at the Standard on Sunset, he watched her exhale her cigarette smoke by the pool, her eyes watching us together as if already viewing the future we could not yet see. Mystical. He knew her when he would come to visit me in the UK, stay for three weeks in our small north London apartment, buy us cocktails when we went out, buy us takeout when we stayed in. He knew her. They had gone on walks to the pub alone together, they had discussed music and bands and rock and roll together. He had been the jury to her in-home fashion shows, told her which dress looked best so that she inevitably picked the other dress he hadn't mentioned. He had been blessed with a nickname, "A." Simple, yes, but an honour from Larissa. A badge of inclusion, a sign that he was down. He knew her too. And yet I can't think of his pain and loss, there is no fucking space in this house for both of our tears. There is no space. Despite my relishing other people's sorrow down a phone line I refuse to let Adam cry, I cannot bear witness to that. My grief lives here now and there is no fucking room. I drink a lot that night. I play her voice notes and I cry, too loudly for someone with a young baby in the house. I call her phone even though I know it is in police custody. Somewhere within me, somehow, there is a part that defies logic. I steel myself to hear her voice on the other end, and every time I do not, I am surprised. You know that burning feeling in your eyes when you have been crying too long? That trite little phrase "I am all cried out"? How true those words ring at three in the morning when I am drunk and forlorn and devastated but unable to muster one single emotion. Adam takes me into bed, I assume, I don't remember how but suddenly that's where I am. Adam's care of me barely registers. It will only be much later that I will mull it over and think of all the little things he did to keep me alive. Fragmented sentences to Adam. I am writing a history book with my words; I am relegating her to the past tense. I get out half a tale about her before I stop, I cannot finish it. I cannot finish the story because to finish it would be to set it in stone, to cement her as a relic and a character instead of the flesh-and-blood person I want to keep believing she is. Excerpted from The Dead Are Gods by Eirinie Carson All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.