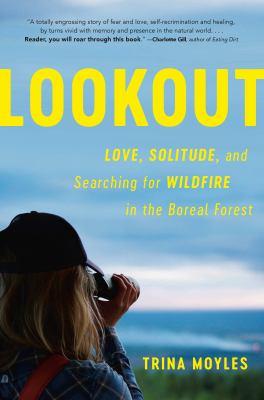

Lookout : love, solitude, and searching for wildfire in the boreal forest

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Stamford | Available |

Browse Related Items

| Subject |

| Moyles, Trina. Fire lookouts > Canada > Biography. Fire lookout stations > Canada. Wildfires > Canada. |

| Genre |

| Autobiographies. |

- ISBN: 9780735279919

- Physical Description 313 pages ; 24 cm

- Publisher [Place of publication not identified] : [publisher not identified], 2021.

Content descriptions

| Bibliography, etc. Note: | Includes bibliographical references. |

Additional Information

Lookout : Love, Solitude, and Searching for Wildfire in the Boreal Forest

Click an element below to view details:

Excerpt

Lookout : Love, Solitude, and Searching for Wildfire in the Boreal Forest

The ranger backed his truck up to the helicopter. The material contents of my life for the next four months were stacked high in the back of the truck: boxes of food, jugs of drinking water, clothes, bedding, two bins of books, a carving knife, acrylic paints, a yoga mat, a ukulele, and a 12-gauge shotgun. "Here we go," the ranger exclaimed with a wide grin. His name was Jim. It was too perfect, I thought. Ranger Jim. He was an East Coaster who'd worked in the North for decades. "Let's go say hello to the pilot," said Jim. I jumped down from the truck and followed him over to the helicopter, a huge, glossy machine painted Camaro red. It was a medium-sized helicopter with ten seats in the back and two in the front, powerful enough to carry over two thousand pounds. Unit crews, who were considered to be the giants of firefighters, typically flew eight-man crews in mediums. Helitack crews, generally the first responders to wildfires, often flew with four-man crews in smaller helicopters. I was grateful we were taking the larger machine--I worried my gear wouldn't fit. "Uh, is that your dog?" asked the pilot, pointing behind me. I looked back over my shoulder to see Holly parading down the runway, her leash trailing behind her. She must have jumped out of Jim's truck window. Oh shit, I thought. "Don't piss off the pilots," they told us at the tower training. Great start, I thought, chasing after her. The vet had recommended giving Holly a mild sedative an hour before the helicopter ride. I kept waiting for it to kick in, for her eyes to close, her head to droop low, but here she was now, hyped up and prancing down the runway with the energy of a puppy. She must've picked up on my frenzied energy. AWOooooo! she yowled comically. I apologized, but the pilot just laughed. "Let's get this show on the road!" he said playfully, motioning for us to start hauling everything in Jim's truck over to the helicopter. The pilot expertly stacked the boxes in the back of the machine. Twelve hundred and eighty-five pounds--that's how much my material life weighed. Jim scribbled passenger names and the total weight onto the flight manifest. The pilot bent down and heaved Holly up into his arms, nudging her into the dog kennel in the back seat. I saw the flash of fear in her eyes. "Take the front seat," Ranger Jim instructed me. "That way you can get a closer look at what's around your tower." I pulled myself up into the front and my hands fumbled with the seat belt as the pilot started up the machine. The rotor blade began whirring. The noise thundered, then deafened, so I reached for the headset above my seat. My heart hammered in my chest and throat and ears. The doors closed and the blades accelerated. The pilot grinned and flashed me the thumbs up. I gave him the A-okay sign, though I thought for a second about drawing a finger across my neck and putting a swift end to everything. We peeled off the earth. The helicopter hovered for a split second above the ground before ascending straight up, up, up, up. Adrenalin coursed through my body like the mountain streams after winter's thaw, full-bodied, eager to move, to go somewhere, anywhere. I gawked at the earth below, the dried grass blowing like a wild mane of hair. Civilization shrinking to childlike proportions: miniature airplanes, buildings, cars, and highway. From a bird's-eye view, how insignificant the civilized world seemed. Everything slid away. Goodbye, farmhouse. Goodbye, power lines. Goodbye, highway. "26, this is Tango Whiskey Victor," said Ranger Jim, transmitting a flight message to the radio dispatchers in Peace River. "Tango Whiskey Victor, go ahead for 26," replied the dispatcher. "You can check TWV airborne off the Peace River airport," said Ranger Jim. "We're heading north with myself and passengers Trina Moyles and Holly the Tower Dog on board." "That's all copied, 26." Leaving. It wasn't hard for me to do. I was reminded of my nineteen-year-old self, boarding an airplane to Central America for the first time, and my twenty-seven-year-old self, sleeping overnight in Heathrow Airport on New Year's Eve and boarding a half-empty jumbo jet for Entebbe, Uganda. Only now I was flying towards a destination that didn't exist on any map. No man's land. Few had journeyed to the fire tower. It was a place that barely registered in people's imaginations, as distant and intangible as Antarctica. The boreal forest unfurled below like a handwoven rug, rolling into the blue band of horizon. I had flown above far-flung landscapes before--rainforest and desert and mountains and oceans. But I'd never flown north of the fifty-sixth parallel, the place where I grew up. I'd never seen the boreal forest from the perspective of a soaring bird. The tapestry blended together aspen, birch, pine, and white and black spruce. The deciduous trees hadn't yet donned their leaves, and the birch buds blotted the landscape with a meek red hue, barely noticeable. Sunlight illuminated the stands of pine, which appeared more golden than green. The black spruce was snarled and misshapen, ugly as a snaggle tooth. Up north, beauty is a crooked thing, like a bone that's been broken again and again. We flew north of the Notikewin River, a tightly coiled, snaking waterway that takes days to paddle. I peered below and spied a moose, bedded down in the grey brush. Then a pair of trumpeter swans, two white specs afloat on a brown, murky lake. A small black dot moved along a seismic line, a narrow corridor used to transport and deploy geophysical survey equipment: Ursus americanus , an American black bear, tiny, minuscule from above. I hoped the seismic line wouldn't lead to my tower. The boreal wasn't pristine--it wasn't as untouched as I had dreamt it would be. Human influence was evident in the number of straight lines savagely slicing up the forest: cutlines, seismic lines, winter roads, access roads, all running parallel and criss-crossing. It was scissor work. Hardly any plant life grew from where machines had scraped down to mineral soil. It would take decades for many of these cutlines to grow life again. Many of the roads led to square clearings where men had built machines to penetrate deep into the soil and suck up what lay beneath. Crude oil and sour gas. Many of the well sites had long been abandoned. Larger companies sold off depleting fossil fuel reserves to smaller companies, and small companies often couldn't foot the costs of environmental reclamation. Pathways like the seismic line favoured some wild things: wolves, cougars, and bears, predators that could zip easily along a line while on the hunt. But they were death traps for woodland caribou, who were hunted by the wolves with increasing ease and frequency. That and the logging industry had severely fractured and depleted their habitat. Caribou dwelled in old-growth spruce and fed on intricate tufts of lichen that grew and dangled from the trees' lowest, oldest limbs. It took decades to grow old coniferous forest and lichen and ensure the survival of one of the boreal's oldest ungulates. "Will I see any caribou up at my fire tower?" I'd asked my dad before leaving. "Not likely." He shook his head solemnly. According to my father, who'd flown over caribou herds in the Peace Country for three decades, the majority of herds would soon be reduced to the symbol on the tails side of a Canadian quarter. There was a good reason biologists called them the "grey ghosts" of the forest. "There it is," said the pilot, pointing towards a gentle, sloping hilltop. I strained to see, but the vibration of the helicopter dislodged my vision. Then everything came into focus: the fire tower, a thumbtack half pressed into the rolling carpet of trees. We drew closer and closer. I felt panic rising in my chest. "So, Trina, you'll notice that you've got a lot of coniferous around your tower," crackled Ranger Jim's voice over the radio. I glanced over my shoulder and the pilot gestured out the window. But no, I hadn't noticed. I couldn't take my eyes off the tower. I could barely breathe as my gaze locked on that silver filament rising up out of the earth. H-O-M-E. Excerpted from Lookout: Love, Solitude, and Searching for Wildfire in the Boreal Forest by Trina Moyles All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.