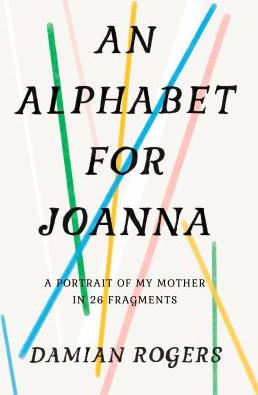

An alphabet for Joanna : a portrait of my mother in 26 fragments

An Alphabet for Joanna is award-winning poet Damian Roger's memoir about being raised by a loving but unreliable single mother who struggles with mental illness only to be later diagnosed with frontal-lobe dementia.

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Stamford | Available |

Browse Related Items

- ISBN: 9780735273030

-

Physical Description

print

323 pages : illustrations ; 22 cm - Publisher [Place of publication not identified] : [publisher not identified], 2020.

Additional Information

An Alphabet for Joanna : A Portrait of My Mother in 26 Fragments

Click an element below to view details:

Excerpt

An Alphabet for Joanna : A Portrait of My Mother in 26 Fragments

Many months before Joanna's short escape, I stayed at a friend's empty house in Buffalo, and visited my mother at the nursing home every day for a week. Each day I dropped down deeper inside her world. On my second visit, we retreated to her shared room. Her roommate wasn't there. Beside Joanna's single bed stood the last surviving piece of the bedroom set she'd inherited from her mother, an antique dresser topped with a bevelled-edged mirror in a curving walnut frame. I'd arranged for this to be used instead of the bland dresser issued with the room. There was a brass keyhole in the top drawer, but if there had ever been a corresponding key, it had been lost years ago. Joanna sat on her bed and examined a wall-mounted fluorescent light fixture, running her fingertips over the bubbled texture of its yellowed plastic shade. She gestured toward it, invited me to appreciate its enigmatic power. "I like this," she said. I faced her in a chair I'd dragged in from the TV area across from the elevators. I'd positioned a meal tray so that it was between us, an improvised work space. I'd covered its surface with an array of coloured markers and two pages torn from a sketchbook. When I'd visited the day before, there hadn't been any photos on her side of the room, but now I noticed she had found and propped up three pictures on her dresser. There was a framed photo of my son, Levi, that I'd given her for Christmas four years earlier, when he was a newborn, and there were two loose snapshots. One was of the base of the Eiffel Tower, which Joanna had taken during our weekend trip to Paris together in 1994. The other photo was of me. I picked up this last picture and studied it. I'm sitting by myself on the blue-and-green floral couch in our living room in suburban Detroit. I'm probably fifteen years old. I'm wearing a baggy acrylic sweater and my hair is pulled back against my head on the sides, a big puff of curled bangs clawing at my eyebrows. Everything in this photo now looked ugly to me: my clothes, the pink walls behind me, the purple calico print tablecloth on the side table, that awful couch, the ruffled muslin curtains my grandmother had made for us, just like the ones in her own house. Joanna leaned forward, her soft, plump arm touching mine, and she too looked at the photo in my hands. "You're my beautiful baby," she said. I kissed her cheek. The room was dark. I crossed to the window over her roommate's bed and pulled the fraying cord to raise the blinds. I sat down on the edge of the mattress and looked out through a tangle of bare tree branches to the street below. Joanna had followed me over, and she stood behind me as we looked out the window silently for a moment. Then she pointed across the street and said, "You see that thing there . . . " "I'm not sure what you're pointing at, the houses or the cars parked on the street?" Her dark brows drew together. "I don't know," she said, and turned away from the window. We settled back on her side of the room, sitting again with the meal tray I'd set up between us. I used the little speaker on my phone to stream the Beatles record she owned when I was little, back when we lived with my grandparents. It was the only record she had salvaged from the two years she lived in California before I was born. "What colour marker do you want to use first?" I asked her. She hesitated and then pointed to purple, looking back up at me for reassurance. "Oh, that's a great choice," I said. My mother held the marker awkwardly, looking down at it uncertainly. "Here, I'm going to draw a circle on the page like this, and you can colour it in," I said as I drew a wobbly round blob. "Oh, you're doing such a good job," she said. After some hesitation, she slowly started to make short purple strokes along the inside of the circle. I continued to praise her as I drew a cluster of triangles and dots on my own page. After a while, she stopped moving her hand to watch mine. "Yours is so beautiful," she said. "So is yours," I told her, but I couldn't redirect her attention back to her own page. "Here, we'll draw this together," I told her, putting my own drawing away in my bag. My phone played one of the Beatles' many hits from the year she went to see the band play Olympia Stadium in Detroit with her girlfriends. That was the year she turned fifteen. She'd told me about that show, how she couldn't hear a single note they sang, the music drowned out by the sounds of the girls screaming around her. We sang along--"She loves you and you know that can't be bad"--as our heads bent toward each other over the purple ring Joanna had made in the centre of the page. I added a black dot in the middle of the ring, then drew round petals around the perimeter, making a psychedelic flower with a cartoonish eye at its centre. "Oh, that's nice," she said. I continued to draw on her page, asking her to choose colours for me. "We'll do this together," I said again. "We're collaborating." I adjusted my sense of time as we sang and I drew, listening to the whole double album with the door shut. We dropped out of time and space. We were the only two people in the world. We were alone at the bottom of an ocean. Someone knocked and the door opened. It was John, a man I'd met the day before in front of the nurses' station, beside the TV. He had told me he loved me as he shook my hand. He had the red face, bright-blue eyes and silver brush cut I associate with Midwestern football coaches. Like Joanna, he was wearing loose-fitting elastic-waist pants and fuzzy socks with no-slip strips. No shoes. "Oh, hi!" he said, lighting up as he saw me. "What are you girls doing?" "Oh, we're just spending time together," I said lightly, and looked back down at the drawing. "I told you yesterday that I loved you," he said. This guy, I thought, and kept drawing. "This is my baby," my mother said, her hand on my arm. "Isn't she beautiful?" "Yes, I told you that yesterday," John said. He turned his square body to me again. His eyes glinted in the flat fluorescent light. "Can I kiss you?" He was blocking the door. "Nope," I said with a big smile. He smiled too. "Okay, I won't do anything you don't want. But I love to see you. Why don't you visit more?" I winced. "I live in Canada," I told him. "Oh," he said, satisfied. "When are you coming back?" "Soon," I said. "I'll be back soon." "Okay, you come see me. I love your mother, but I really love seeing you." He winked. "I'll leave you girls alone now." Joanna and I returned to our own zone again, but the spell was soon broken by screams on the other side of the door. My mother was not disturbed; she seemed to not hear the noise at all. I pretended I needed to go to the bathroom as an excuse to open the door and look out . . . "You can just go to this one in here," Joanna said, pointing to the bathroom between her room and the one next door. "Um, okay, I just want to--" I poked my head out. I could hear a fight, but I couldn't see a thing. "It's okay, I'm fine," I said, pulling my head in and shutting the door again. When I opened the door an hour later to walk to the elevator with my mother, a woman of indeterminate age sat on the floor in front of me. This is a horror movie, I thought; this is the nineteenth century. The previous year, when Joanna had first moved from a nice assisted-living facility into this rundown nursing home, the only thing she'd said to me was, "There are a lot of people suffering here." She had always been sensitive to the pain of those around her. Not long after this, she lost the ability to speak in complete, coherent sentences. Her current home was the only place that would take her when the assisted-living facility pushed her out of their system--a system I'd chosen for their well-maintained buildings, for their reputation for keeping residents in their care after savings ran out and they transitioned to Medicaid. But my mother's diagnosis of frontal-lobe dementia had made her an unattractive resident. Inappropriate was the word they used when they first approached me about finding her a new place to live. "She's an inappropriate resident." I opened the door from our pocket of calm and saw a woman whose hands were wrapped around the doorknob of the room across the hall from us. The woman was hunched down on the floor with her knees pressed to her chest, the weight of her small, wiry body hanging from her grip on the doorknob. Our eyes locked and she began to sob. As my mother and I passed her, she stood up and followed us, asking for help, trying to get my attention. Joanna muttered, "Just ignore her," as we inched sideways, gripping each other's forearms, toward the elevator. Excerpted from An Alphabet for Joanna: A Portrait of My Mother in 26 Fragments by Damian Rogers All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.