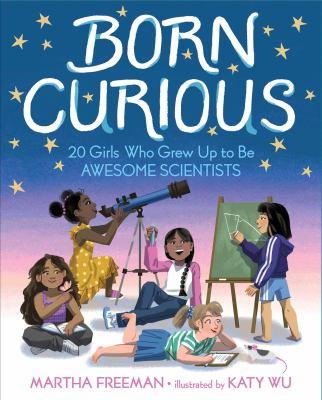

Born curious : 20 girls who grew up to be awesome scientists

A collection of biographies of twenty groundbreaking women scientists who were curious kids and grew up to make incredible discoveries.

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Community Centre | Available |

| Stamford | Available |

| Victoria | Available |

Browse Related Items

| Subject |

| Women scientists > Biography > Juvenile literature. Women > Biography > Juvenile literature. |

| Genre |

| Biographies. |

- ISBN: 9781534421530

- Physical Description 122 pages : color illustrations ; 26 cm

- Publisher [Place of publication not identified] : [publisher not identified], 2020.

Content descriptions

| General Note: | "A Paula Wiseman Book." |

| Bibliography, etc. Note: | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

| Formatted Contents Note: | Introduction -- Ellen Swallow Richards -- Joan Beauchamp Procter -- Frances Oldham Kelsey -- Gertrude Belle Elion -- Rosalind Franklin -- Marie Tharp -- Vera Cooper Rubin -- Tu Youyou -- Sylvia Earle -- Lynn Alexander Margulis -- Patricia Era Bath -- Christiane Nusslein-Volhard -- Jocelyn Bell Burnell -- Shirley Anne Jackson -- Ingrid Daubechies -- Adriana Ocampo -- Susan Solomon -- Carol Greider -- May-Britt Moser -- Maryam Mirzakhani -- Afterword: So you want to be a scientist. |

Additional Information

Born Curious : 20 Girls Who Grew up to Be Awesome Scientists

Click an element below to view details:

Excerpt

Born Curious : 20 Girls Who Grew up to Be Awesome Scientists

Ellen Swallow Richards ELLEN SWALLOW RICHARDS GEOCHEMIST 1842-1911 MARCH IS THE QUIETEST month on the farm near Dunstable, Massachusetts, so every year the family takes a break and visits relatives in Vermont, Maine, and New Hampshire. The distances are short, but this is the 1840s, and the only way to travel is by wagon. Every trip becomes an adventure. Bumping along in the back, tucked in blankets, the little girl with the serious gray eyes listens to her parents argue. Mama--always a worrier--says the still-snowy road is too dangerous, and they should turn back. But Papa, driving the team of horses, says that's nonsense. The roads are well-traveled and, "Where any one else has been, there I can go." All her life, the girl will remember this motto of her papa's and think that while it's true enough, it doesn't really suit her. What she wishes for herself is an adventurous spirit, one tough enough to do things no one else has ever done. As a child, though, Ellen Henrietta Swallow--known as Nellie--was kept plenty busy with routine chores at home. Her mother got sick a lot. Her father had his hands full with the farm, which never brought in much money. It was up to Nellie to cook, wash, iron, clean, and even hang wallpaper. Nellie liked some of the work and took pride in doing it well. By the time she was ten, her embroidery and her baking had won prizes at the county fair. Nellie's pursuits were not confined to the house. She also drove the cows to pasture, pitched hay and--best of all--kept a garden. All her life Nellie loved flowers and plants. In a letter to her cousin and best friend, Annie, she bragged about her amaryllis and geraniums. Nellie was good at schoolwork, especially Latin, and when she graduated from the Westford Academy--the equivalent of today's high school--she wanted more education. Unfortunately, her family was having the usual money troubles, and there was none to spare for her to go to college. So Nellie decided to earn the money herself. By this time her father had opened a general store. She worked the counter, kept the accounts, and went to Boston to buy supplies. She also gave Latin lessons. Most important, she saved like crazy, living for a while on a diet of only bread and milk. Two years passed, and still Nellie did not have enough money for college. In 1866--when she was twenty-four--the hard work, the scrimping, and the frustration combined to make her sick. Till then Nellie had always been a bundle of energy, but suddenly she couldn't so much as get up off the couch. Today we would probably call the problem depression. She called it "purgatory, the time when my own heart turned against me." How she overcame her sickness is not clear, but later she would write, "When you feel an indication of a certain morbid feeling, resolutely set your mind in another direction, and don't give up easily. Let the mind know there is a willpower to control it. This is possible." By the summer of 1868, she had a plan, which she announced to a friend like this: "...I have been to school a good deal, read quite a little, and so secured quite a little knowledge. Now I am going to Vassar College to get it straightened out and assimilated." Vassar College in New York State was only seven years old and exclusively for women. (Today men attend Vassar too.) Nellie was twenty-five when she enrolled, and from the moment she got there she loved it. Among her professors was the astronomer Maria (pronounced Mar-EYE-ah) Mitchell, whose life story would inspire astrophysicist Vera Cooper Rubin (see page 31 ) six decades later. Maria encouraged Nellie to become an astronomer, but Nellie chose to focus on chemistry. She believed being useful was part of her Christian duty. She thought knowing chemistry would make her useful, but she had no idea how. Nellie researched the chemical composition of iron ore at Vassar, then went to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). She was the first woman to earn a degree in chemistry in the United States, and the first woman to study at a technical institute. In 1875 Nellie married an MIT professor of mining engineering, Robert Richards. The two spent their honeymoon in Nova Scotia with a few friends--Robert's entire class of future engineers. Eventually, the couple would travel all over the world studying rocks, mining, and mineral processing. In 1879, Nellie became the first woman to join the American Institute of Mining and Metallurgical Engineers. Nellie had worried about money all her life. While doing her graduate studies at MIT, she made ends meet by running the boarding house where she lived. Now she was helped out by her husband's salary and could put her scientific training to work. At last she could be useful the way she had always intended. Remembering her own frustrations seeking more education, she founded MIT's women's laboratory, a place for science teachers (almost all women) to learn more about the subjects they taught. Soon after that, she developed an advanced chemistry program at the Girls High School in Boston. Later, she would become an instructor of sanitary chemistry at MIT, the first woman to serve on the MIT faculty. In 1876, she and Robert renovated a house to show off her ideas about environmental and domestic science. Among other things, they installed special windows to improve ventilation, removed lead pipes to clean the drinking water, and built a drip irrigation system for Nellie's beloved houseplants. Nellie's dedication to bringing science home led her to test foods to determine how nutritious they were, and to calculate exactly how much gas was required to cook different meals. The result of that and similar research was the field now known as home economics, or family and consumer science. Nellie founded the American Home Economics Association and wrote ten books on nutrition, housing, sanitation, and health. She also helped establish the New England Kitchen, which came up with inexpensive ways to prepare healthy food. From that project came the first school lunch program in the United States. In 1887, the Massachusetts state department of health asked Nellie to improve drinking water for the people in and around Boston. As usual, she was energetic, working fourteen-hour days, seven days a week, to test some 40,000 water samples and using the results to make a map of water pollution in Massachusetts. Based on her research, the first water quality standards were established in the United States. Later, Nellie would start a business that analyzed air, food, fabric, mineral oils, and even wallpaper to make sure they were safe. As a student at MIT, Nellie had done the work for a doctorate in chemistry, but the university refused to give her the degree. It would have been the first graduate degree in chemistry from the school, and some professors thought it would look bad if it went to a woman. Almost one hundred years later, MIT established a special professorship for a distinguished woman scientist. From 2012 to 2016, climate scientist Susan Solomon (see page 83 ) was the Ellen Swallow Richards professor at MIT. ELLEN SWALLOW RICHARDS Achievement: Geochemist who founded the fields of sanitation engineering and home economics and helped establish the first standards for clean drinking water. Quote: "You cannot make women contented with cleaning and cooking, and you need not try." Fascinating fact: In college, Nellie Richards and her friends tried to cure themselves of the habit of using "bad" language, including expressions like "My goodness!" Any time a girl got caught, she had to pay a few cents as penalty. Nellie never had to pay. Excerpted from Born Curious: 20 Girls Who Grew up to Be Awesome Scientists by Martha Freeman All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.