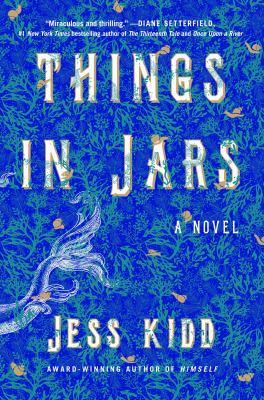

Things in jars : a novel

London, 1863. Bridie Devine, the finest female detective of her age, is taking on her toughest case yet. Reeling from her last job and with her reputation in tatters, a remarkable puzzle has come her way. Christabel Berwick has been kidnapped. But Christabel is no ordinary child. She is not supposed to exist. As Bridie fights to recover the stolen child she enters a world of fanatical anatomists, crooked surgeons and mercenary showmen. Anomalies are in fashion, curiosities are the thing, and fortunes are won and lost in the name of entertainment. The public love a spectacle and Christabel may well prove the most remarkable spectacle London has ever seen.

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Community Centre | Available |

| Stamford | Available |

Browse Related Items

| Subject |

| Women detectives > England > London > Fiction. Kidnapping > Fiction. Anatomists > England > London > Fiction. Conspiracies > Fiction. Humanity > Fiction. London (England) > History > 1800-1950 > Fiction. |

| Genre |

| Detective and mystery fiction. Thrillers (Fiction) Historical fiction. |

- ISBN: 9781982121280

- Physical Description 369 pages ; 24 cm

- Publisher [Place of publication not identified] : [publisher not identified], 2020.

- Copyright ©2019.

Additional Information

Things in Jars : A Novel

Click an element below to view details:

Excerpt

Things in Jars : A Novel

Prologue PROLOGUE As pale as a grave grub she's an eyeful. She looks up at him, startled, from the bed. Her pale eyes flitting fishy: intruder--lantern--door--intruder. As if she's trying to work out how they all connect, with her eyes cauled and clouded. Is she blind? No. She sees him all right; he knows that she sees him. Now her eyes are following him as he steals nearer. She's pretty. She's more than pretty. She's a churchyard angel, a marble carving, with her ivory curls and her pale, pale stony eyes. But not stone--brightening pearl, oh soft hued! He could touch her: stroke her cheek, hold the wee point of her chin, wind her white curls around his finger. Her lips are beginning to move, pouting and posturing, as if she's working up to something, as if she's working up to sound . Without further thought he puts his hand over her mouth, his skin dark against hers in the lantern light. She frowns and her feet beat an angry tattoo despite the restraints and the coverlet is off. She has two legs, like a girl . Two thin white legs and two thin white arms and not much else in between. Then she stops and lies still, panting. The touch of her: she is like nothing in nature. Skin waxy and damp, breath cold: an unnatural coldness, like a corpse living. And that smell again, stronger now, the sharp salt of the open ocean, an inky seaweed tang. She fixes him with her pearly eyes. He feels the slick nubs of her teeth and the quick, wet probe of her tongue on his hand. The man fancies that his head is opening like an easy oyster, the child is tapping and probing, her fingers are inside his mind. Touching, teasing the quivering insides. She is dabbling and grabbing as with a jar of minnows, splashing and peering as with a rock pool. She hooks a memory with her little finger and drags it out, and then another and another. One by one the child finds them, his memories. She cups them in her palm, shimmering, each a perfect tear. A boy slips on wet cobbles, himself, following a cart with a potato in his hand. A woman turns in a doorway with the sun on her hair, oh, his brother's wife! A four-day-old foal stands in a green field, a pure white flash on its lovely nose. The child tips her palm and watches the tears roll away. Panic floods the man. Something swells in him--a pure and compelling disgust, a strong sudden urge to finish this creature off. To throttle her, stove in her face, snap her neck as cleanly as a young rabbit's. A voice inside him, the lisping voice of a child, mocks him. Isn't he the most ruthless of bastards, wouldn't he smother his own mother without a care? Hasn't he done all things, terrible things, not stinted on the things he's done? And here he is frightened to grant the kindest of mercies . The man looks at the child in dismay and the child looks back at him. He loosens his grip on her and takes out his knife. A lantern dips and flares in the doorway and here's the nurse. An ex-convict with a few years on her and a lame leg, clean of garb but not of mouth, used to bad business. Likes it, even. The others behind like her personal guard--two men, neckerchiefs up around their faces. Odd birds; elbows tucked in, heads swiveling, light-stepping, listening, blinking. With every step they expect an ambush. "Don't touch her," the nurse says to him. "Get away from her." The man, looking up, hesitates, and the child bites him, a nip of surprising sharpness. He pulls his hand away in surprise and sees a line of puncture holes, small but deep. The nurse pushes past him to the side of the bed, glancing at his hand. "You'll regret that, my tulip." She makes a show of pulling on fine chain-mail gloves and unhooks the restraints that hold the child to the bed, dressing her in a harness of strong material, one limb at a time, buckling the child's arms across her chest, lashing her legs together. The child lunges, open mawed. The man stands dazed, flexing his hand. Red lines track from palm to wrist to elbow, the teeth marks turn mulberry, then black. He twists his forearm and presses his skin. Sweat beading on his forehead, his lip. What kind of child bites like this, like a rat? He imagines her venom--he feels it--coursing through him, from arm to heart, lungs to bowels, fingertips to feet. A blistering poison spreads, a sudden fire burning itself out as it travels. Then the lines fade and the marks dull to no more than pinpricks. All the time the creature watches him, her eyes darkening--a trick of the lamplight, surely! Two eyes of polished jet, their surfaces flat, so strangely flat. The nurse is speaking low, standing back to direct. "Roll her, bag her, make haste, watch her mouth." They wrap the child in canvas, a staysail to make a hammock of sorts. The man, manipulating his arm, examining the pinpricks, suddenly finds himself beyond words. He makes a sound, a vowel sound, followed by a string of gargled consonants. He drops to his knees, like one devotional, and falls backward onto the hearthrug. He would scream if he could, but he can only reach out. He lies gasping like a landed catch. From the floor he watches the two men lift the bundle between them. They move with deliberation, as if underwater. The nurse limps over, lantern in hand, and looks down at the man. Her diagnosis: he is in a bad way, face as gray as his county crop. Not old but already life-waned--and now this. He begins to sob. The nurse could sob, too, for the loss of a good thief, the kind who'd abstract the teeth from your head without the opening of your mouth. She kneels with difficulty. "Close your eyes, lad," she whispers. "It will help me no end." Trussed in a canvas hammock she's no weight. But the two men would carry a far heavier burden with greater ease. Of course they'd humored the nurse, heard her stories in the tavern with a few inside them. But they see it now, in the child, as she said they would: all kinds of wrong. What of the man fallen? They balked to touch him after. The carrying of him would be worse than the leaving of him and they feel the leaving keenly. The child swings swaddled between them, big eyed in the lantern dimmed; oh, they see it now, in her. By the time they reach the landing the men are sweating with the effort of not dashing her head against the wall. One would shoot her through the eye in a heartbeat; the other would cut her throat in a blink. At the top of the stairs they are in danger of hurling her down. The nurse keeps them in check. Giving whispered orders, steadying them with her strong fingers on arms and ribs. Bringing them back to the job at hand, for the money. "Don't think on it!" The nurse speaks urgent and low. "Don't think on anything. Hoist her, aye, and we'll be gone." The big house is silent tonight, but for our intruders moving through corridors with their trussed burden and breath-held shuffle. Awake to loose floorboards and creaking doors and light sleepers. But the servants slumber on. The housekeeper, tidy bedded, neat of nightcap and frill (like a spoon put away for best), inspects the linen cupboards of her dreams. Smiling at immaculate piles, heaven fresh, as clean as clouds. The butler, proper, even in his nightshirted sleep, patrols an endless cellar. The bottles giggle in dark corners. They ease out their corks and call to him in honeyed voices. They sing songs of laden vines and sunny hillsides and duty forgotten--liquid bewitchment! He grips his lantern and will not stop. The housemaids, in their attic nests, are dreaming of omnibuses and pantomimes. The cook snores fruity, unpeeled, and well soaked under warm sheets, as solid and brandy scented as plum pudding. She dreams of matchless soufflés; she hunts them down as she sails in a saucepan over a gravy sea. All are senseless in the tucked-in, heavy-breathing, before-dawn quiet. The big house is silent tonight, but for our intruders, hurrying out of the servants' door. The dogs lie poisoned in the yard, their muzzles flecked with spittle, a breeze ruffling their fur. This is the breeze that came over the sea, miles inland, past wood, fields, and lane to whisk the gravel on the drive and dance around the rooftop chimney pots and whistle through the keyholes. The mice are wakeful and so, too, is the mean-eyed kitchen cat who needles after their fat pelts, sly and silent. This snake-tailed stalker watches the figures hasten across the cobbled courtyard, throwing moonlit shadows in their wake. The barn owl sees them as they round the house. She ghosts above on silent wings. The lord of the manor. He, too, is awake. A lamp burns in his study as he frets and puzzles, considers and adjusts. He bends over his writing, his handsome whiskers peppered with gray, his brow furrowed. He could be a fortune-teller, the way he's inventing the future, coaxing and muttering it into being. The shadows pass outside, crossing the terrace. Perhaps hearing their footsteps, the lord of the manor looks to the window but, remarking no change in the night sky, returns to his plans. The shadows move quickly over the lawn, toward the gate, two with swag slung between them, one following, limping. The bundle is cradled over the ground. The child feels the grass whip under her canvas hammock. She feels the night air on her face and takes a breath of it and lets out a sigh you can't hear. The sea rocked asleep, now wakes and answers, a refrain of waves and shale song. The rain in the sky that is yet to fall, answers; a storm gathers. All the rivers and streams and bogs and lakes and fens and puddles and horse troughs and wishing wells wake and answer, adding their voices: faint and rushing, purling and gurgling, muddy and clear. The child looks up. For the first time she can see the stars! She smiles at them, and the stars look back at her and shiver. Then they begin to burn brighter, with renewed fever, in the deep dark ocean of the sky. Chapter 1 CHAPTER 1 The raven levels off into a glide, flight feathers fanned. Slick on the rolling level of rising currents and downdrafts, she turns her head, this way and that. To her black eye, as black as pooled tar, London is laid out--there is no veil of fog or mist or smoke-haze her gaze cannot pierce! Below her, streets and lanes, factories and poorhouses, parks and prisons, grand houses and tenements, roofs, chimneys and treetops. And the winding, sometimes shining, Thames--the sky's own dirty mirror. The raven leaves the river behind and charts a path to a chapel on a hill with a spire and a clock tower. She circles the chapel and lands on the roof with a shuffling of wings. She pecks at brickwork, at lichen, at moth casts, at nothing. She sidles up to a gargoyle and runs her beak affectionately around his eyes, nudging, scooping. The gargoyle is a creature designed to vomit rainwater from the gape of his mouth onto the porch. The parishioners (when there were parishioners) blamed the blocked gutters, but it was always the gargoyle, holding back only to let go a sudden flood upon the faithful below as they stood at God's threshold, looking up to the heavens, flinching. The raven hops to the edge of the porch roof and peers down. A woman is standing below: she looks up, but she doesn't flinch. Bridie Devine is not the flinching kind. What kind is she, then? A small, round upright woman of around thirty, wearing a shade of deep purple that clashes (wonderfully and dreadfully) with the vivid red hair tucked (for the most part) inside her white widow's cap. She presents in half-mourning dress, well cut but without flash or fashion. On top of her widow's cap roosts a black, feather-trimmed bonnet of a uniquely ugly design. Her black boots are polished to a shine and of stout make. The crinoline is no friend of hers; her skirts are not full and she's as loosely laced as respectability allows. Her cape, gray with purple trim, is short. This is a practical woman, or at least a woman who finds it practical to be able to fit through doorways, climb stairs, and breathe. At her feet, a doctor's case, patched and antiquated, the leather buttery from handling. She takes from her pocket a pipe. Here's a teaser: a fast habit in one so seemly ? And isn't there a canniness to her smoking in the shelter of a deserted chapel (and not puffing down the Strand with a chinful of whiskers and a basket on her head)? The raven eyes her with interest. The woman winks at the bird. There is a world of devilment in her wink. The raven responds with a soft caw. The bird gauges the gargoyle. No water falls; the gargoyle is dry-mouthed, the lips frame an empty grimace. Reassured, the raven takes to the air. Bridie Devine watches the raven fly out of sight. Now all that's moving in this chapel yard are her thoughts, she thinks. The occasional cart or carriage passes the open gate. Otherwise there is a wall of a decent height between Bridie and the world and that is enough. Bridie breathes out, turning her face up to the sun: autumn warmth, fuller-bodied and lovelier than summer heat, with the mellow dying of the season in it. Bridie welcomes it on brow and cheek. That the sun has found a clear patch of air to shine through (in these days of smoke-haze and mist and fog) ought to be appreciated. Bridie is alone with the sun and her thoughts and her pipe. The pipe is unremarkable: clay made, shaped to sit snug in the hand or in a tooth gap, of a cheap variety favored by Irish market harpies. Short of stem and small of bowl so that the nose of a hag may overhang and keep the rain off the tobacco. The pipe may be unremarkable but the contents are anything but. To her usual twist of any mundungus Bridie has lately been adding a nugget of Prudhoe's Bronchial Balsam Blend. A crumbly, resinous substance that burns with a pleasant incense scent followed by a lancing chemical stink. This is less unpleasant than it sounds, being simultaneously bracing and dulling. You add lots of Prudhoe's Blend for colorful thoughts and triple that amount for no thoughts at all. Prudhoe's Bronchial Balsam Blend is just one of the recreational creations of Rumold Fortitude Prudhoe, experimental chemist, toxicologist, and expert in medical jurisprudence. Prudhoe's previous legendary blends, Mystery Caravan and Fairground Riot, proved either blissful or petrifying. As such, these blends continue to attract loyal followers among his more adventurous friends, Bridie being one of them. But now Bridie's pipe is empty. She has smoked it all. Bridie puts the bit of her empty pipe in her mouth, just while she's thinking. A drop more tobacco would be nice. It wouldn't have to obliterate her thoughts, just line her lungs. She'll smoke anything: earthy and wholesome or treacly and nasty, street peddler's dust or gentleman's savor. As if in answer, in the far corner of the chapel yard, a wisp of smoke wends its way up into the air. Bridie takes this as a sign. Bridie looks down at the man sprawled by the showy tomb of a successful family butcher. Two things strike her as immediately wrong. Firstly, the man is deficient of clothing (his wardrobe consisting, in its entirety, of: a top hat, boots, and a pair of drawers). Secondly, she can see through the man. She is able, with perfect ease, to read the inscription on the tomb that should, by rights, be obscured by the body of the man. She can even see the angels on the decorative stone frieze. This is an ingenious trick--like Pepper's ghost! There will be mirrors, screens certainly, black silk or some such, an illusionist's contraption, a phantasmagorical contrivance. A rudimentary search of nearby graves turns up nothing. Bridie is baffled. If no external explanation for the presence of this transparent, partially clad man is evident, the cause must be internal . She cannot recollect transparent partially clad men being a symptom of the consumption of Prudhoe's Bronchial Balsam Blend. But the list is long and includes many adverse reactions, from sweating of the eyeballs to sensitivity to accordion music. She resolves to inspect this apparition, systematically, from crown to toe. A top hat is tipped down over the eyes of its owner. Like its owner the hat is transparent. Despite this, Bridie can see that the hat has known better days. It is dented of body and misshapen of rim. The transparent man is naked to the waist; below the waist he sports close-fitting white drawers, tight at the thighs, sagging at the knees. The boots on his feet are unlaced and his fists are sloppily bound with unraveling bandages, none too clean. He is massive of chest and biceps, strong shouldered and thick necked. And tattooed: stern to bow. Below the tipped-down hat rim: a nose that hasn't gone unbroken, a clean-shaven jaw, and a shining black mustache (generous in proportions, expertly waxed, certainly rococo). In the mouth, a pipe lolls. A draw is taken from it, intermittently. The smoke has dwindled to a wisp now and has no discernible scent. On inhalation the tobacco in the pipe bowl glows blue. Bridie wonders if the man has a pinch of tobacco to spare and, if so, whether that's likely to be transparent too. The man, perhaps sensing her presence, pushes up his hat idly. His eyes open and meet hers. He springs to his feet in alarm, holding his fists up before him. He is nothing short of miraculous. The tattoos that adorn his body--how clearly Bridie sees them now--are, in fact, moving. She is put in mind of Monsieur Desvignes's Mimoscope. A device of cunning construction (a wonder among wonders at the Great Exhibition), pictures looped between spools, illuminated by a spark. Bridie, transfixed, saw animals, insects, and machinery--static images--flickering to life, to bounce and flutter, slither and winch. Bridie watches this man with the same fascination as, in one continuous motion, an inked anchor drops the length of his biceps. High on his abdomen an empty-eyed skull, a grinning memento mori, chatters its jaw. A mermaid sits on his shoulder holding a looking glass, combing her blue-black hair. On finding herself observed the mermaid takes fright and swims off under the man's armpit with a deft beat of her tail. On his left pectoral an ornate heart breaks and re-forms over and over again. He is a circus to the eye. "Had a good look?" he asks. Bridie reddens. "Forgive me, sir, if I startled you. I was after borrowing a smoke." She gestures to her empty pipe. The man lowers his fists. "Merciful Jesus, it is you . Is it not?" His expression turns to one of delight. He sweeps off his hat. "Oh, darling, do you know me?" Bridie stares at him. "I do not." "Ah now ..." He runs a hand over shorn hair, black velvet, dense as a mole's pelt, and wrinkles his strong square forehead. "Your name is Bridget." "My name is Bridie." "It is." The man nods. "Your full appellation, if you would be so kind?" Bridie hesitates. "Mrs. Bridie Devine." The man grins. "What else would it be, with those eyes divine?" He pauses. "And Devine would be your husband's name, madam?" " Late husband, sir," corrects Bridie. The man bows. "My sincere condolences, Mrs. Devine." Bridie turns to go. "If you'll excuse me, sir." "Won't you stay, Bridget? We could talk about the old times." Bridie stops. "Sir, you are quite mistaken in your belief that you know me--" "But I do know you: you are Gan Murphy's girl." Bridie's eyes widen. "I know he was your master, your gaffer." The man pauses, his expression amused. "You don't remember me at all, do you?" Bridie looks at him in desperation, sensing a game that could go on for all eternity. "That is not the point, Mr.--" "Doyle." He wanders to a grave across the way and gestures down at it. "Not a bad spot, is it?" Bridie follows him. She reads the headstone: "THE DECORATED DOYLE" Here lies RUBY DOYLE, Tattooed SEAFARER and CHAMPION BOXER Untimely taken, 21 March 1863 "He felled them with a bow" "Do you know me now?" asks the dead man. "Well, sir, you are a boxer by the name of Ruby Doyle. You have been deceased half a year, and still I do not know you." Ruby Doyle puts his hat back on. "Throw your mind back, Bridget." He taps his topper down at the crown. "Think awhile. I'm in no hurry." "If this is some kind of trick, Mr. Doyle--" "Ruby, if you please," he says, with a rakish tip of his hat rim. "What trick?" "You being dead." "Trick's on me." "I do not believe in ghosts, sir." "Neither do I--why do you not?" "I have a scientific mind. Ghosts are a nonsense." "I agree." "A parlor trick." Bridie looks at him hard. "Smoke and mirrors." Ruby smiles disarmingly. "A chance to pull one over?" "A fashionable flimflam." "And what of table-tipping?" Ruby, who seems to be enjoying this, scans the heavens: "Send me a sign, Winifred." "Dark, overheated rooms and suggestible types." "Half of London is at it!" "Half of London is duped. To believe in the existence of ghosts, spirits, phantoms--that one can see and converse with them--is deluded." "Are you deluded, Bridget?" "I see you, sir, but I do not believe you exist." Ruby Doyle is crestfallen. Bridie frowns. "If you will excuse me, I have work to do." "Churchyard work, is it?" He glances slyly at the bag in her hand. "Is there a shovel in there? Let me guess: you're a resurrectioner, like your old gaffer, Gan?" She rounds on him. "And I look like a resurrectioner? I help the police." "Do you, now. In what way?" "Working out how people died." "How did I die?" "A heavy blow to the back of the neck." "Now, that's clever. But you read about it in the Hue and Cry ?" "I did not." " Boxer bested in tavern brawl. I'd survived this fella trying to knock me to pieces, stepped in for a quick celebratory one and then--" "Ruby, I'm wanted in the crypt. They have found a body there." "That'll be the place for it. Off you go, so. And my compliments to your gaffer--how is your old guv'nor Gan?" "Dead. In jail." Ruby stops smiling. "Then I am sorry. Gan was one of those fellas that go on: a long, thin strip of gristle, everlasting. Do you not see him too?" Bridie regards the man with desperation. "Gan is dead." "Then am I the only dead fella you see?" "Appears like it." "What about Mr. Devine?" Bridie looks puzzled. "Your late husband," Ruby prompts. "You must see him?" "Never." "Then I'm peculiar to you. Are you surprised, Bridget? Are you rattled?" "Nothing surprises or rattles me." "Is that so?" He reflects on this a moment, then: "Can I come with you, watch whatever it is that you're doing in the crypt?" "You may not." Bridie walks through the gravestones. Ruby ambles alongside her. The boots, unlaced, lend a loose parry to his boxer's strut. At the edge of the path she stops and turns to him. "I am hallucinating. You are a waking dream." She bites her lip. "You see, I smoked something a little stimulating earlier ..." Ruby nods sagely. "The empty pipe--is it Kubla Khan you're visiting?" Bridie is dumbfounded. Ruby gestures at his bandages. "Ringside doctor, recited while he patched." When they reach the chapel, Bridie holds out her hand. "This is where we part company." Ruby smiles; it's a charming kind of a smile that gaily remakes the contours of his fabulous mustache. His eyes, in life, would have been a handsome dark-molasses brown. In death, they are still alive with mischievous intent. "I would shake your hand, Bridget, but--" Bridie withdraws her hand. "Of course. Good day, Ruby Doyle." She heads into the chapel. "I'll wait for you, Bridget," calls the dead man. "I'll just be having a smoke for meself." Ruby Doyle watches her walk away. God love her, she hasn't changed. She's still captain of herself, you can see that; chin up, shoulders back, a level green-eyed gaze. You'll look away before she does. She has done well for herself, with the voice and the clothes and the bearing of her. If it were not for that irresistible scowl and that unmistakable hair, would he have recognized her? But then, the heart always knows those long-ago loved, even when new liveries confuse the eye and new songs confound the ear. Does Ruby know the stories that surround her? That she was an Irish street-rat rescued from the rookery by a gentleman surgeon who held her to be (ah now, this is a stretcher!) as the orphaned daughter of a great Dublin doctor. That despite her respectable appearance (it is rumored among low company), she wears a dagger strapped to her thigh and keeps poisonous darts in her boot heels. That she speaks as she finds, judges no woman or man better or worse than her, feels deeply the blows dealt to others and can hold both her drink and a tune. Ruby Doyle meanders back to his favorite spot, to muse on all he knows and all he doesn't know about Bridie Devine, lighting his pipe with the fierce blue flame of the afterlife. The curate of Highgate Chapel is battling the locked door to the crypt with his collar pulled up and his hat pulled down. On seeing Bridie, his face betrays surprise, which turns to displeasure when she reminds him of her business. The vicar is expecting her in relation to the delicate matter of the walled-up corpse. The curate fixes Bridie with a look of profound begrudgement and, managing to unlock the door, leads her into the crypt. The corpse is propped in an alcove behind loose boards. Discovered by workmen clearing up after a flood, now abated. More than a few Highgate residents blame both the flood and the resurrected corpse on Bazalgette's subterranean rummagings. All well and good creating a sewerage system that will be the envy of the civilized world, but should one really delve into London's rancid belly? London is like a difficult surgical patient; however cautious the incision, anything and everything is liable to burst out. Dig too deep and you're bound to raise floods and bodies, to say nothing of deadly miasmas and eyeless rats with foot-long teeth. The rational residents of Highgate defend Mr. Bazalgette as a first-rate engineer and deny the existence of eyeless rats. The corpse had been immured in an alcove; its shackles and wide-socketed expression of terror suggest foul play. But the body is clearly of some age, lessening police interest in the case. This is a bygone crime in a city flooded with new crimes. The coppers are up to the hub in it: London is awash with the freshly murdered. Bodies appear hourly, blooming in doorways with their throats cut, prone in alleyways with their heads knocked in. Half-burnt in hearths and garroted in garrets. Folded into trunks or bobbing about in the Thames, great bloated shoals of them. Bridie has a talent for the reading of corpses: the tale of life and death written on every body. Because of this talent, Bridie's old friend, Inspector Valentine Rose of Scotland Yard, passes her the odd case--with the understanding that she stops short of a postmortem, her unqualified status being a bar to this procedure. The cases usually have two things in common, other than having piqued Rose's interest: bizarre and inexplicable deaths, and victims drawn from society's flotsam (pimps, whores, vagrants, petty criminals, and the insane). For her considered opinion Bridie receives a stipend (paid, unbeknownst to Bridie, from the pocket of Rose himself) and signs her report with an illegible signature. If anyone asks, her name is Montague Devine. In the event that she is called to give evidence, she'll give it in a frock coat and collar. With the curate's help Bridie clears the remaining stones from the alcove. The crypt is a grim space, with a vaulted ceiling and flagstone floor. As with many subterranean, lightless places it has the climate of a year-round winter. The recent flood has left a rich, peaty smell not unlike a dug bog. The corpse, a woman, Bridie judges, by size and apparel, is well preserved, allowing for her lengthy entombment. A macabre spectacle decked in finery. There is a cruel theatricality to her, costumed as if for a tableau vivant. A tragic heroine, a goddess--an unknown figure from history! Her gown, rotten now, could be Grecian, Roman. Her pale hair, shedding in clumps, falls onto withered shoulders. Bridie divines last moments spent shackled by the neck in the suffocating dark. It is there in the open mouth, stiffened around a howl. The curate fusses with the lamp, swearing under his breath. He is a young man with an unfavorable look about him. Slight of stature and large of head, with light-brown hair that cleaves thinly to an ample cranium with bumps and contours enough to astound even a practiced phrenologist. His complexion is as wan and floury as an overcooked potato and his mouth was made for sneering. Otherwise, Bridie notes, he is shabbily dressed for a curate and vaguely familiar. "Sir, have we met?" she asks. The curate regards her blankly. "I think not, Miss--" "Mrs. Devine--I didn't catch your name, sir." "Cridge." Bridie resumes the examination. Trying to ignore Mr. Cridge straining to see past her. The corpse's injuries (bone-deep lacerations to her right arm, three broken fingers, shattered mandible, fractured orbital) tell a dark story. A shawl hides her left arm. Bridie carefully unwraps it. "She has a child," she says. A baby, swaddled, no bigger than a turnip, lies in a sling beneath the folds of its mother's shawl. Bridie feels a flood of pity. There hadn't even been space to sit, pressed as they were into a shallow recess, so this woman had died standing and her baby had perished alongside her. Mr. Cridge leans in nearer and bites his lip, wearing an expression of ghoulish excitement. Bridie is offended on the victims' behalf. "If this is at all disturbing for you, Mr. Cridge, I suggest you leave me to it." "I'm not in the least disturbed. How old is the infant?" "At death: a few months old. It suckles still on its mother's finger." Bridie peers closer. "The baby isn't suckling the mother's finger, it's gnawing it." "Well, I'll be damned!" The curate raises his eyes to the ceiling. "Apologies." Bridie frowns. "The lantern, Mr. Cridge, as near as you can, please." Bridie sees the baby's face, wizened now, its features vague and leathery. Bridie puts the tip of her finger into the infant's tiny mouth cavity, gently pushing past the mother's shriveled digit. "They are like pike's teeth," she says, astonished. "Irregular needles in the upper and lower jaw, sharp yet." "How about that ..." murmurs Mr. Cridge. "I will need to remove the corpses for a thorough examination in decent light." "That will be impossible," says Mr. Cridge sourly. "At least, not possible today." "It must be today; the police will expect my report." "The vicar is out." "Then I shall wait for him." "I will raise this matter with him directly he returns, Mrs. Devine." "Please make sure that you do, Mr. Cridge." The curate turns from the corpse to Bridie with a look of such concentrated enmity she is in no doubt: if he could, he'd shove her into the alcove and wall it up again. Mr. Cridge closes and locks the gate behind them and pockets the key. "I would strongly advise you to keep the nature of this discovery to yourselves, Mr. Cridge," says Bridie. "London has a taste for aberrations." "I can assure you that this matter will attract the utmost discretion on our part. Good day to you, Mrs. Devine." The curate puts his hat on, bows resentfully, and heads off toward the vicarage. Bridie surveys the chapel yard: it is empty of partially clad, imaginary dead pugilists. Then she catches sight of it, bobbing into view above the top of the wall: a top hat. A hat that has known better days, dented of body, misshapen of rim, and transparent. With a firm hold of her case Bridie takes flight, around the side of the chapel and out through the back gate. She continues along the street alone--once or twice glancing back over her shoulder, with a mixture of relief and something approaching disappointment. Bridie, crypt-cold to the bone, is glad to be aboveground. As she descends Highgate Hill, below her, in the acidulated smoke atmosphere, London glimmers. She follows the hidden Fleet townward, as the sky darkens and streetlamps are lit and the gaslights are turned up in shops and public houses. Past St. Giles, Little Ireland, where the tenements totter and the courts run vile with vice. New Oxford Street marches down the middle. The Irish hop over it and spread out to the north, forming new footholds. They have flooded this town, wave after wave of them, spilling out from their rookeries to perch in all places. On the south side, the buildings turn their backs on the main road, leaning inward, like gaunt conspirators. Change is always drawing near. Innovation waits like an offstage actor, primed and ready in the wings, biting its lip and grinning. Rag-plugged windows and crumbling bricks will give way to open landscapes of stone and sky. The rats and the immigrants will be sent running. But for now, the slums are as they have always been: as warm and lively as a blanket full of lice. Bridie could find her way with her eyes shut and her nostrils open. Try it now. Close your eyes (eyes that would be confused anyway by the labyrinthine alleys, twisting passages, knocked-up and tumbling-down houses). Breathe in--but not too deeply. Follow the fulsome fumes from the tanners and the reek from the brewery, butterscotch rotten, drifting across Seven Dials. Keep on past the mothballs at the cheap tailor's and turn left at the singed silk of the maddened hatter. Just beyond you'll detect the unwashed crotch of the overworked prostitute and the Christian sweat of the charwoman. On every inhale a shifting scale of onions and scalded milk, chrysanthemums and spiced apple, broiled meat and wet straw, and the sudden stench of the Thames as the wind changes direction and blows up the knotted backstreets. Above all, you may notice the rich and sickening chorus of shit. The smell of shit is the primary olfactory emission from the multifarious inhabitants in Bridie Devine's part of town. Everyone contributes, the Russians, Polish, Germans, Scots, and especially the Irish. Everyone is at it. From Mrs. Neary's newborn crapping in rags to Father Doucan squatting genteelly over his chamber pot. Their output is flung into cesspits, cellars, and yards, where it contributes to London's perilous reek. Bad air (as any man of science worth his monocle will tell you) sets up stall for the latest bands of traveling diseases. Cholera is the headlining act. When cholera comes to visit you'll find the lanes empty. Cholera keeps the women and the children from pump and square and the men inside scratching their arses. When cholera comes to visit, the streets are quiet. There is no bustling to and fro, no gossip and ribald laughter, only fervent prayer and the dread of an unholy bowel movement. Mercifully there is no cholera today and so the streets are full. Full as only London is full--and the din of it! Chanters, costers and traders, omnibuses thundering along thoroughfares, horse hooves at a clip and carriage wheels at a growl, carts and barrows at a rumble, and all of London jostling in all directions at once. Bridie heads home. Excerpted from Things in Jars: A Novel by Jess Kidd All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.