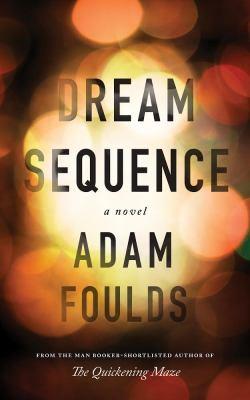

Dream sequence : a novel

Henry Banks, a brilliant but narcissistic young actor, is prepared to go to any length for a role, to capitalise on his successes in television drama by securing the lead in the latest film by a celebrated Spanish director. He is on the brink of the next step -- very close to achieving intellectual credibility and some serious celebrity. However, Henry has -- unwittingly -- become an important part of the life of recently-divorced Kristin: someone who is also on the brink. Sitting in her beautiful, empty Philadelphia home, Kristin is obsessed with the handsome English actor and convinced they are destined to be together. She resolves to fly to London and bring their relationship to fruition.

Other Formats

Browse Related Items

| Subject |

| Actors > Fiction. Divorced women > Fiction. Stalking > Fiction. Canadian fiction. |

| Genre |

| Psychological fiction. |

- ISBN: 9781771962810

- Physical Description 183 pages ; 21 cm

- Edition First edition.

- Publisher [Place of publication not identified] : [publisher not identified], 2019.

Additional Information

Dream Sequence : A Novel

Click an element below to view details:

Excerpt

Dream Sequence : A Novel

Excerpt from Dream Sequence The beautiful house was empty. Kristin watched from the front window as her sister climbed into her snow-spattered car and drove away, shuttling from one set of worries - Kristin - to another - the noisy, complicated, enviably involving struggles of her family life. Suzanne had left behind a liveliness in the air through which she had moved and talked. Kristin walked back to the kitchen where there were syrupy breakfast plates to clear. She transferred them to the small dishwasher and sucked her sweetened thumbs. Diversify, Suzanne had said. Find some other activities and interests. She used a clear, careful voice with Kristin at the moment, stripped of challenge and controversy. In Kristin's mind Suzanne's broad, freckled face still hovered, neutral and patient, ready for her reaction. I understand you not getting a job for a while if you don't have to. You're in a great situation, when you think about it. Perfect fresh start time. Craig thinks ... Kristin didn't care what Craig thought. Craig was entirely unsympathetic. Craig was most of the problems Suzanne was now shuttling towards in her rattling Kia on the road back to Pottstown. Craig thought that Kristin had got it made: married to her boss, divorced by her boss and now entitled by law to the lifestyle to which she had become accustomed. You won the Rollover, he liked to say straight to her face and smiling, as though she wouldn't hear the dirty joke he was pretending he hadn't made. Craig was the sort of dumb and nasty that thinks it's smart. Often, when Suzanne's back was turned, he looked at Kristin, just looked at her for as long as he felt like it, smoking and thinking things. Kristin was upstairs now, deciding whether she needed to change the sheets of the bed where Suzanne had slept. Kristin lowered her nose to the creased fabric and thought not, catching only a sharpness of lavender. She removed a long curving hair from the pillow and tugged everything straight. Kristin had painted the upper rooms of the house in colours she had seen on The Grange, a British TV programme that had in the most extraordinary way become a very important part of her life. In the show, the walls of the rooms where the wealthy family lived were painted in rich and sombre colours she didn't like but the servants' rooms downstairs had lovely colours that she spent many hours with swatch books seeking to match. Blues and greens that were spacious and honest, that had a dignity and sadness that were ideal as the containers of her new, ruined life. Not that Kristin spent much time in the upper rooms. The bedding in this one was white, voluminous, heavy, and made soft crunching sounds as she rearranged it. All neat again. A border of broderie anglaise, an intricate pattern of holes, ran across the top of the comforter. Kristin had with great care and attention to detail redecorated her marriage away. Everything was now to her taste and signified her ownership of this desirable rowhouse. Removing all traces of Ron had been a relief but changing her stepsons' rooms was painful. They had only been there for the odd weekends that Ron had them but Kristin had always loved that rushing influx of youth and energy, even if, except for the youngest, Lionel, they had not liked her back. Beautiful little Lion. The older boys would glare or speak in grudging single words while staring at their devices, but Lion recognised her kindness, her eagerness, and needed it, coming slowly closer and closer. Now she had removed the clutter and colourful walls of childhood and replaced them with tasteful, impeccable adulthood. Sometimes she regretted it. Kristin decided to go to yoga. That was another activity and interest. Suzanne didn't even know. Kristin went to the room with her wardrobe and changed from pyjamas into the soft second skin of her exercise clothes. Over them, she put on her long quilted coat and collected her mat and bag. When she went to the front door, she found mail lying there, one piece, for Ron: a catalogue for a clothing company that he had never got round to cancelling. Kristin knew it well, mature men in outdoor wear posing in landscapes, fishing, striding, drinking out of enamel mugs with their shirtsleeves rolled. It would go straight into the trash. She was not his PA any more. It was maddening that she still had to deal with these things. Kristin pulled at it to tear it in half but it was too thick. The pages just twisted in her hands. The whole Ron situation had begun with tasks performed for him, note taking and letter writing and appointments in his diary and travel bookings and gifts for his wife and children. When he formed his own company, she went with him. Those morning drives away from traffic out of Philly into greenness and landscape and his big house near Valley Forge, the crackling sweep of his gravel driveway, that long wrong turning in her life. He was still there, with a new wife now, his third. And Kristin was alone. Almost alone. Kristin liked walking along with the rolled mat poking out of her tote bag. The spiral of foam was a recognised thing. People knew what it was and saw her walking brightly along, supple and sensitive and responsible. The walk was twenty minutes of mostly straight, harsh road but she liked to do it. Almost no one walked but she did. Kristin was in tune with a different time, historical and civil, walking in the salted channels between crusts of snow with the quick chirping British voices of The Grange talking in her head. Kristin admired good penmanship too and handwrote her letters to Henry Banks in navy ink. She tried to make them so beautiful and neat that they looked like you could put the pages upright on a stand and play them on a piano. She put on her hat and gloves and went out. Henry. Henry was everywhere and nowhere, shaping everything. He was the key signature in which the music of her life was played. The cold air was rough and quick, the light under grey clouds a thickened white. Unseasonable weather. They were barely into fall and this snow had come suddenly swinging down from the north, flinging whiteness. Kristin liked it, the thrill of this unexpected change. She walked with poise and purpose, her yoga mat protruding from her bag. Behind the front desk at the yoga centre, the girl's familiar face looked strongly exposed, floating in front of the cabinet of t-shirts and water bottles, smiling Buddhas and detoxing teas, as though it had been cropped out of a different photograph. 'Wow,' Kristin said. 'I like the hair.' 'Oh, thank you,' said the girl, lengthening her neck with a slight inclination of her head as though the hairdresser were still circling her with a mirror to show her all the angles. 'Dramatic,' Kristin said and the girl looked directly at her. 'It's great,' Kristin repeated. 'I thought, you know, this could work for me.' 'Oh, it works. Maybe I should take the plunge instead of.' Kristin took hold of her braided ponytail and lifted it up to the side, demonstrating its weary familiarity. 'You have to invite change, don't you? Step into the new. Where did you get yours done?' The receptionist hesitated. 'Where did I get it cut?' she asked. 'Yes,' Kristin read her name tag, 'Layla. Where did you go?' 'Well.' 'It's okay. You don't have to tell me.' 'No, no. I was.' 'It's fine. I understand. We can't all have it done. I probably don't want it anyway.' 'It was at Salon Masaya, on Frankford Ave. You have such beautiful thick hair is all. And along with those bangs, so cute.' 'I know. I'm a lucky person,' Kristin said. 'In a lot of ways.' Kristin pushed through the double doors, splitting the lotus flower logo painted on them, and left Layla behind as the doors swung back together. Now, having entered the sanctuary, from small speakers overhead came the sound of flowing water, encouraging a peace of mind that had not been achieved by the small dog shifting from foot to foot outside the main practice room. Laurie was taking the class. Kristin didn't think that Laurie should bring her pug with her, though everyone fussed over it and knew its name, Jasmine. The pug was adorable but unfairly so, because of its indignities, its crushed bulging features, wet and black, its short scraping breaths and urgent, inept waddle. Kristin scratched its furrowed scalp and pulled a velvet ear through her fingers before she went in. Hard to know if Jasmine even noticed. It reacted only to the opening door and shuttled forwards. Kristin kept it back with a raised foot and shut the door. 'Poor thing wants her mommy.' Kristin turned to see the man who'd made this comment, tall and soft in the middle, a dark bulb of hair, smiling. Around him, four women were readying themselves in different areas of the room. 'But if I let her in,' Laurie said, 'she'd be licking at your faces and blowing her breath over you and you wouldn't want that.' 'No, probably not.' Laurie stood on large livid feet, shaking her long fingers loose. Her flesh had been subdued with years of practice. Her belly lay meek and flat behind jutting hipbones. Hair scraped back, skin clear as rainwater, she smiled generally into the room, a kind of facial hold music, while Kristin deposited her bag and coat and unrolled her mat in a space between the others. 'Okay, okay, yogis,' Laurie said. 'Somehow it's wintertime already but there is still a sun behind those clouds to salute, so.' She stretched up and poured herself down into the first asana. The others followed, growing upwards, folding in half. Kristin stretched and breathed through the hour, seeing the room in different perspectives, the wrinkled cloth at her knees, her red and white fingers on her mat. Periodically, Jasmine scratched at the door. Kristin looked through the hoop of herself and saw the others in similar knots and star shapes. She felt vibrant with exertion, her heart beating heavily, sweat in her hair. Henry, the things I do for you. Afterwards, they lay in corpse pose and the lights and shabby ceiling tiles drifted like clouds overhead. Kristin liked lying in corpse pose, at the bottom of things, her bones resting on the floor, like she'd sunk to the bottom of the ocean, discarded. Dying and dying and dying. The relief of a final state. As she sometimes did, Laurie decided to share an inspirational thought to close the class. 'It is suddenly cold and dark,' she said, her voice deeper and slower after the hour's yoga. 'It feels like the end of the year, like we're all about to hibernate. But you ask a naturopath, or a farmer, or anyone who really understands natural cycles, and they'll tell you this is the beginning. The seeds are falling into the earth and will start germinating now, under the snow, underground. New futures are growing, new possibilities. So while you lie there at rest at the end of our cycle of activity, think of yourself as a germinating seed about to get up and walk into your future.' Oh it was wonderful how if you were open the world told you what you needed to hear which was what you already knew. Kristin was alive with her very particular future. Suzanne had no need to worry. It would happen. The connection was made. Kristin had been reborn before, when she had met her twin soul, Henry Banks, by chance, on her way down to the Virgin Islands for a vacation. She remembered so well the strange dazzling period of realisation that the whole world had changed, down in the blue Caribbean. There was that butterfly that flew into her room and stayed there for several days, its unbelievable colours dancing and gliding. When it settled on her bedspread or curtains she could see the crystalline pattern of its wings, bars of glowing green, dots of yellow, its round, alien eyes and sensitive antennae. You can see the whole universe in a butterfly if you really look, its intricate, perfect machine. It was a sign. That was obvious. It bounced up. It sailed in curves. The butterfly had come to tell her that everything was going to be all right. After Laurie rang the bell that marked the end of the session, Kristin was the first to leave, her warmth sealed inside her coat. She allowed Jasmine with great relief to scuttle in through the opened door. During the class more snow had fallen. Kristin walked quickly home into a fresh, speeding wind. Cars thrashed wetly past. On the corner at a cross street the wind whisked up the surface snow and spun it in a little tornado and stopped and did it again. The wind must always spin like that, Kristin suddenly understood, only now it was visible. The snow illustrated the wind and Kristin, noticing, had a little bit more of the secrets of the world revealed to her, things you can't see but are as true as true. The world is a magical place. At home, she showered and washed her hair. On the edge of her bed, she bowed into the blast of the hairdryer. From the kitchen, she collected some crackers and baby carrots and dip and took them down to the den. The den was the part of the house where she was most comfortable, warm and half-underground, the snow blue against the glass of the windows. The rest of the house, perfected and separate, hovered overhead. She turned on the TV. If she didn't turn on the TV the silence could accumulate. Amazing how the silence could gather and get louder and louder and seem almost to be about to explode, like a faulty boiler shaking its pipes. It could give her pressure headaches. The TV kept it at bay. She settled on the sofa. Her hair was fragrant and light and voluminous. Before she started the TVO of The Grange she had her alerts to check on her iPad. Nothing new had come up for Henry's name on Google. She checked Twitter for mentions. Something in a language she didn't understand which when translated was just about the show going out that night in their country. In a way, it was a relief to search around and find nothing. The searching was stressful, unpredictable, thrilling sometimes, making her heart jolt with a new photograph or a new lie about his personal life. And there were so many people with stupid opinions, people who had never even met him who thought they knew something about him. Less of this now that the final season of The Grange had been aired with a frightening flurry of coverage. Sometimes she wished the whole online world didn't exist to confuse her connection with Henry. Once it had all been so simple. He'd held her hand. One day he would again. She set the iPad down, next to Spiderman. Spiderman lay on the sofa beside her, small and plastic, his stiff arms and legs raised as if for action, holding a stomach crunch position. Lion, little Lionel who loved her, had given her Spiderman one day without telling her. And Spiderman had become a crucial part of the story. It all added up. Kristin picked up the remote and flipped on an old episode. When Henry appeared, she thought she would tell him about the wind and the snow and about what Laurie had said about seeds in winter in her next letter. She would start on it later. Letters flew past all that electronic noise and went right to his hands. Henry's movements on the screen, his expressions, the exhilarating moments of his smiles, his emotions, the dialogue in that beautiful accent that she could speak along with - it was all a timeless connection. She ate and she watched all the precise little moments, her mind fully fastened to them. She could stay like this until the daylight darkened and the neighbours' cars, returning from work, passed like aeroplanes overhead. * The hunger was beginning to hurt. Three days of grinding emptiness, of heat and sudden flutterings in the left side of his body. The relief of small meals in the evenings, monkish bowls of rice and green vegetables that he perceived so sharply, his senses attuned to the rising steam, the warmth and aroma. And afterwards the velvety sensation of being fed that allowed him to fall asleep. In the morning he was hungry again. It was working. It was worth doing. He was becoming what he needed to be, to convince GarcÃa who, finally, was in London to see him. But it would be a mistake to fast today. He needed energy. He went to his kitchen and ate a banana and two large handfuls of nuts, enough food to relax and feel well but not enough to dull his sharpness. He ate and hummed to himself. He dressed. He ran his hands down the smoothness of his abdomen. His body was tight. His trousers hung from his hipbones. He chose a khaki linen shirt with button-down pockets that he thought had the right sort of feel: serious, adaptable, with connotations of the military and the desert. Henry checked how he looked in the mirror. Henry's face was something everybody had to deal with, to assimilate and get over, even Henry. When Henry caught sight of his face he often felt as though he were arriving late at something already happening. His face looked so finished and authoritative. He had the approved lines, the symmetry; he looked how a man should look. His handsomeness could be a shock, as much for him as for others who sometimes also had to process their recognition of him, their sensation of an untethered and inexplicable intimacy. Occasionally Henry thought that it would be nice, warm and relaxed and human, to be a little ugly, to have a face that showed personality in pouches under the eyes or a large, soft mouth, the face of a character actor, expressing suffering and humour. His own good looks were bland, Henry thought, mainstream, televisual. Hunger seemed to be improving it, its calm masculinity now fretted with sharpness and shadows. Henry had observed long ago that cinematic faces were not normally attractive, not attractive in a normal way. They did not belong on Sunday evening television or in clothing catalogues or any realm of the conventional ideals. The truly cinematic actors, that is. Look at Joaquin Phoenix with his dark stare and scarred mouth or Meryl Streep's long thin nose and subtle, not quite sensual mouth, her large and frightening eyes, her affronting vulnerability. All of them, when you thought about it: Christopher Walken, Jack Nicholson. Bogart and Hoffman and Day-Lewis. Of course the actresses tended to be more straightforwardly beautiful but then overwhelmingly so. Think of the wide landscape of Julia Roberts's smile, an American landscape, honest, expansive, full of hope. No, up until now, Henry's face had been of the reassuring kind that made for success on TV. It had lacked the strangeness and astringency that made for cinema. But now, perhaps, it was coming, with age, with hunger. He observed himself in the mirror. He said, 'Ba-ba-ba-ba-ba-ba. Pa-pa-pa-pa-pa-pa. Red lorry. Yellow lorry. Red lorry. Yellow lorry. How are you today? I'm fine, sir. How are you today?' He checked his phone to see if his taxi had arrived. It hadn't. He stepped out onto his balcony to smoke a cigarette, cupping the lighter flame from the blustery river air. A whirring sound: straight and fast, a cormorant flew low over the water. He should be looking at his pages again. He threw the cigarette away and went in. He picked up the pages and glanced at them, reminding himself. He bounced up and down on the balls of his feet, swinging his arms. 'Ba-ba-ba-ba-ba,' he said. 'Pa-pa-pa-pa-pa. You can't just walk in here whenever you like. You just can't.' His phone chimed. The taxi was outside. According to the text, Omar was driving. Henry had booked a taxi because he wanted safety between his flat and Soho, a protected preparatory calm. The bike ride was too long, too raw, too sweaty, and he almost never used public transport now. You never knew what might happen. He put the pages in his satchel. He paused in the centre of the room to practise a facial expression, the animation of a friendly and relaxed greeting. He dropped the expression from his face. He bounced again on his feet then walked on. Locking the front door behind him, he immediately missed the safety of his flat. It would be there to receive him again, to hide him, after whatever it was that happened later in the day. On the shelf by the exit door he had post. Two letters. He put them into his satchel and stepped outside. The taxi was a large black people carrier with tinted windows. Inside, he said to the neck in front of him, to the bejewelled hand on the gear stick, 'Hi, Omar. You know where we're going?' 'Got the address here. Greek Street.' 'That's the one.' Not wishing to talk any more, Henry pushed his headphones into his ears and put on his pre-meeting music. Years ago at university, as a music scholar, a member of his college choir, he had sung Renaissance polyphony. A sense of competence and self-confidence suffused him when he heard it now. The plainchant of the opening statement, low and horizontal, was followed by the higher voices joining one after the other, merging, ascending, passing one another, opening a great fan of sound. Calm and ethereal, a translucent grid laid over his view of Docklands, of Limehouse and east London passing outside his window. He hummed along with Palestrina's tenor line. In the comfortable hollow of his leather seat, he watched the people outside, the Muslims with waistcoats and hennaed beards, the young mothers, the hipsters of Whitechapel over time giving way to the suited office types of Gray's Inn and Holborn: London's surplus of faces, of human versions, every permutation, all preoccupied, unconscious, milling towards something. At traffic lights the taxi slowed for him to observe a man on a corner holding a phone to his ear and eating an apple, delicately picking with his teeth at the remaining edible flesh by the core. A cyclist shuttled past his window. All these people, blind to his presence behind darkened glass. They would be interested in him, most of them. Their expressions would change. The taxi progressed in halts and short surges into Soho. Henry checked his watch. Good, he wasn't too early. He plucked the flowing harmonies from his ears, paid Omar and stepped briefly into the movement of the street. Keeping his head low, hunched forwards, he walked to a discreet glass door with gold lettering and pressed the buzzer. There was no voice but the door buzzed. Henry pushed it open. He was met by a young man of the assistant type descending the stairs, what Henry's friend Lucas had once referred to as 'one of those little shits with the hair'. On his t-shirt, much more striking than his actual face, was a very realistic drawing of a gorilla wearing large headphones. He had a pen in his mouth which he removed to say, 'Hi, it's Henry, isn't it?' as if he didn't know. 'Come on up', as if he owned the place. The guy put the pen back in his mouth and headed up the stairs. Henry followed. At the top, Henry was met by Sally, the casting director, a quiet, tightly organised woman, a great encyclopaedist of talent, and one of the most important people in the business. Often it was those people who seemed the least artistic, like they could work happily in any other business. They spoke in the universal language of professionalism, not one that Henry had been obliged particularly to learn. Sally Lindholm could just as easily have run a government department. 'Henry, how nice to see you. Thank you for coming in. How are you?' Thank you for coming in. The pretence that this was an equal relationship was something that Henry was used to ignoring. The answer to the question how are you was always to be kept brief. Genuine as her friendliness may be, Henry knew not to talk with any unnecessary personal detail. The space accorded for his response was like a box on a form to be filled out. It could only contain so much. 'I'm good, I'm good,' he answered. 'You're looking well,' Sally said. Her friendliness was real enough. It was other people's - actors' - responses to her that couldn't be trusted. They were always straining, eager, beaming, and Sally was like royalty, accepting this as normal, possibly at this point unable to tell the difference between the acting and the real thing, or not caring. 'We're ready to go, I think,' she said. 'Oh, really? No waiting area? No fellow actors I have to pretend I'm happy to see?' She laughed. 'Not today. You're spared. Shall we go in?' 'Sure. I'm excited to meet the man himself.' 'Of course. Do you need anything? Water?' 'Just some water would be great.' 'Okay. Seb, could you bring some water for Henry?' The assistant swept the upper mass of his hair from one side of his head to the other. 'I'm on it,' he said. Henry animated his face with warm greeting as he entered the room but he had to wait. GarcÃa was watching some footage on a laptop. A large man, his folded arms rested on his gut. Sitting low in his chair, his face was sunk down into his beard. He held up one hand to stay Henry and Sally then decisively slapped the spacebar. 'Okay, okay,' he said. 'Please.' He gestured at the seat in the middle of the room facing a camera. 'You are Henry.' 'I am.' 'So, I've seen your work. I've seen you on tape. All very nice.' Henry dropped his satchel by the door and sat down, leaning forward towards GarcÃa, his forearms on his knees. 'And I've seen yours, of course. Sueños Locos. The Path to Destruction. The Violet Hour. Bricks. I mean, those are ... They mean a lot to me, those films. It's an honour to meet you.' 'Okay, okay,' GarcÃa exhaled through wide nostrils and shunted his glasses back up his nose. Seb swooped down at Henry's feet then backed away. Henry glanced down and saw a bottle of mineral water. Seb settled himself in a seat beside the camera. GarcÃa said, 'So, Mike. You like this character?' 'I don't know about "like". I think I understand him. I feel him.' 'You think you are like him?' 'Sure. I know where he's coming from, that commitment, that anger. We all are to some extent. That's the genius of it.' GarcÃa didn't smile or response. He hit the centre of his glasses again. 'So we will read a little bit.' Sally said, 'You've got the pages, haven't you?' 'Yep.' Henry raised an arm to indicate his bag. 'But I shouldn't need them. I'm off book.' 'Excellent. Seb, ready to go?' 'Just one ...' He pressed a couple of buttons. A small staring red light appeared on the camera. He gave a thumbs-up. Henry dropped his head down onto his chest, disconnecting, becoming the other thing. He lifted his face. It was tighter, slightly stricken, his gaze significant. 'Julia?' he said. GarcÃa, an unlikely Julia, gruff and heavily accented, said, 'Hey, Mike.' 'Julia, you can't just walk in here like this.' 'The door was open.' 'What does that mean? You walk through every open door you see?' 'Jesus, Mike. I was just passing and I came in to see.' 'You can't do that, Julia. You can't. You can't. I'm just getting things, you know, clear here.' 'Okay,' GarcÃa interrupted. 'Leave it there.' 'Sure.' Henry drained back into himself. Uncomfortable, he reached down for the water bottle and twisted the top but didn't yet drink. 'That first "Julia",' GarcÃa said. 'It can be softer.' 'Okay.' 'And you know he is saying the opposite of what he wants. He isn't sleeping. He isn't eating. The war is in his head all the time. He knows he's in trouble. He wants Julia to come in. You have to say, "You can't just walk in." Underneath it's, "You have to come in. Please."' 'That's what I thought.' 'And "What does that mean?" That line, he's thinking about meaning, he's thinking in a different way, very fast, very conceptual.' 'He's like on a whole other level. He's like, yes, but what does that mean? She walks through every open door she sees? It's a description of her, of her freedom. It's, like, the total contrast to him.' 'Exactly, exactly. Also, a bit angry. "What does that mean?" It's too much for him. We do again.' Henry sighed and shook his shoulders, looking down then up. 'Julia,' he said. 'Hey, Mike.' 'Julia, you can't just walk in here like this.' 'The door was open.' 'What does that mean? You walk through every open door you see?' 'Jesus, Mike. I was just passing and I came in to see.' 'You can't Excerpted from Dream Sequence: A Novel by Adam Foulds All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.