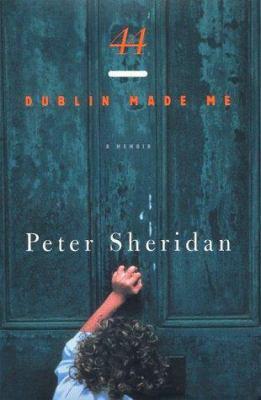

44, Dublin made me

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Victoria | Available |

Browse Related Items

- ISBN: 0670885142

-

Physical Description

print

viii, 278 pages - Edition 1st American ed. --

- Publisher New York : Viking Penguin, 1999.

Content descriptions

| Immediate Source of Acquisition Note: | LSC $41.92 |

Additional Information

44, Dublin Made Me

Click an element below to view details:

Excerpt

44, Dublin Made Me

Chapter One DUBLIN, NEW YEAR'S EVE, 1960 Lodgings available. Center city location. Adjacent to RC church. All modern conveniences. Phone 41966. Da read it back to Ma. She was proud of him. Proud of his way with words. She looked at him and poured more tea into his cup. She had a special way of pouring tea. She poured tea like a countrywoman.    He started to count the letters. Tiptoed his pen from one letter to the next like a ballet dancer, mumbling as he went. Above each word he placed a number like a little crown. - Will I milk your tea, Da?    He ignored her and continued counting. At the end he stopped and gave her a look that needed no words. - You're counting, I'm sorry. He wrote down the word total and beside it the number eighty-four - That's eighty-four characters all told. We won't get eighty-four characters into two lines.    Jimmy Nelson was a character. He worked on the docks. Every year for his holidays he booked himself into a suite in the Gresham Hotel and never left the room. Not to eat, drink, or piss. For two weeks the world came to Jimmy Nelson. That made him a character, and people called him a character. - What's a character, Da? He looked at me over the rim of his glasses - The space a letter takes up is called a character    I loved his way with words, just like Ma did. I loved Ma pouring the tea. I loved the two things about the same.    He pushed the piece of paper in front of me and asked me to delete words but keep the sense. I ran my eyes across the words. Across and back. I paused at the shortest word, to . Adjacent to RC church. I said it in my mind and left out the to . I looked over at Da. The pencil was sitting on the top of his ear, where most men keep their cigarette butts. A little nest of hair hung from his ear, and the stubble on his face looked like ink dots on blotting paper. I took the pencil and drew a line through the word. I turned the page toward him. He looked at it and furled his brow. Then he took the pencil from me and put a line through the word available . Lodgings. Center city location. Adjacent RC church. All modern conveniences. Phone 41966. I looked into his face and smiled. He put his great big fist on my head and rubbed it hard. - You're a right little character. What are you? - I don't know. - A right little character. What are you? - A right little character.    Not so long ago I'd have slapped his hand away. When I had ringlets. Blond cones of hair down to my shoulders. The morning of my first holy communion I stood before the mirror and worked my way up from the brown shoes. The knee-length socks with the yellow stripe. The flecked trousers and matching jacket. The white shirt and the green-and-white school tie. On top of all this a Shirley Temple head. I hated my hair, hated it more than any prison bars. I especially hated the oul' wans who slobbered over it, saying how lovely it was. It was horrible.    I nearly fell off the chair from the force of Da's hand. I had a grown-up haircut just like his. I could rub my finger up the back of my neck, and it felt like pinpricks. Dominoes falling. The quiff on top that stood up for an hour if you wetted it and all day if you used Brylcreem. I wasn't allowed Brylcreem because it stained shirt collars, so it was water all the way, except for the day you got it cut in Mickey Wellington's barber shop, when he gave you a two-handed rub of his magic green lotion. Da never let "foreign bodies" near his scalp. Jimmy Nelson wore so much grease (as Da called it), his hair was a solid mass. Didn't move in a hurricane. Just like the plastic "nigger wigs" that Mickey Wellington sold in his barber shop.    Da pushed me so hard my head went all the way between my knees and onto the chair. I tried to loosen his grip, but it was no use. I slid off the chair onto the floor and his hand followed me like a crane and I punched at him with both fists. - Come on, hit me!    I swung at him wildly. - Have to punch harder than that.    Ma hovered with the teapot. - Are you finished your tea, Da?    I managed to get up from the floor. I swung but missed by a mile. I could never hit him when he held me at bay like this. One day, I thought, one day my arms will be long enough, and we'll see then.    My arms felt like lead weights. I concentrated all my strength into my forehead. I pushed against his hand. Hard as I could. He released his grip, and I fell against his tummy. He wrapped his arms around me and squeezed me tight. - You're a little terrier.    I looked up at him. His face seemed distorted - You finished your tea, Da?    I could see his hairy nose. His nostrils looked like rabbit holes in the dunes on Dollymount Strand. - You've a drop left in this cup, do you want it?    Da let out a crisp, beautiful fart. He whistled with satisfaction. Ma beckoned to me. - Come over here, son.    She lifted his cup from the table. - There's still a drop in that, missus    She handed it back to him. It was a crime punishable by two days' silence to take his cup with a drop still left in the bottom. He drank the dregs with colossal satisfaction. - I'm going down the garage, son. Follow me down    He gathered up his paper, pencil, and the advertisement from the table. He started to undo his belt and headed for the back door.    "Down the garage" was Da's toilet. You got to it by going through the ordinary garage where he kept his tools and his biscuit tins. His bits of old bikes--wheels, frames, tubes, springs, saddles, pedals, crossbars, baskets, back carriers, all manner of spokes, front lights, back lights, dynamos, rust paint, white pump, black pump--and all of these spare parts secured to the wall with stays so that they looked alive.    Opposite bike parts and along one whole wall, pride of place, were Da's ladders. They were Da's other children, his twins. In winter they had their own blanket to keep out the dreaded frost and ice, which might cause them to crack.    The floor of the garage was taken up by two cars--one space rented by Father Ivers, a curate in Saint Laurence O'Toole's church, and the other by Eamon Dooley, owner of the corner shop, the Emerald Dairy.    The entrance to the garage was by a small door from the backyard. At the farthest point from this door, beyond the parked cars and the wall hangings and the biscuit tins, was the remains of a building that looked like a hermit's cell. There were holes in it, all over. It was the holes that kept it from falling down. It had no door and no roof. An old timber joist stretched between two of the holes, and this supported the cistern. The joist was eaten alive by woodworms, who had their own swimming pool because the cistern overflowed from time to time. Da put a sign up on the wall: PLEASE PULL UP HANDLE AFTER USE. The word after was underlined in red ink. Da was the only human being who ever sat down on this toilet bowl, but nothing would convince him that intruders with fidgety hands didn't use it from time to time.    Lower down was the paper holder, designed and manufactured by Da. It was a coat hanger cemented into the wall so that it stuck out like a long spike. Onto this spike squares of paper, neatly cut from old telephone directories, had been placed in alphabetical order. He was currently wiping his arse with the Rs . Da claimed it was an inside toilet, but in the corner was a lady's umbrella in case it rained. It was neither an inside nor an outside toilet, it was uniquely Da's.    As soon as I stepped inside the garage I could see him in jigsaw form through the holes. The smell was awful, but I liked it. It filled the whole garage. It was amazing that a person his size--five foot six and a half, he said, but I'd say he was only five foot five (he always lied about things like that)--it was amazing the stink he could make. Some day that power would pass to me.    I slid past the shiny black Volkswagen (Father Ivers's) toward the portholes. The jigsaw changed like a kaleidoscope. I stopped, stepped back, it changed again. Past the Triumph Herald (Eamon Dooley's), and I could see his paper, opened at the racing page. He ran his pencil down the runners in the twelve-thirty at Sedgefield. - Bastard.     He wrote NWAF beside number six, Garryowen. It was shorthand for Not Worth a Fuck. It could mean the horse, the jockey, the trainer. Or a combination of all three. What was important was the system for picking winners. You were nowhere without a system. A wanderer in the desert. Lost, alone, and abandoned. There are rules and there are fools. Some of Da's rules were: always back the outsider in a three-horse race; never back in a race with less than six runners; trust your own judgment and never take advice; never refuse a drunk man's tip; never gamble beyond your means; beg, borrow, and steal when your system clicks; never gamble on emotion; always go with your instincts; never, under any circumstances, desert your system. That was a cardinal rule, underlined in red ink. I knew not to interrupt him when he was studying form. That was a cardinal rule, too. You could get lynched for putting him off a winner. I didn't mind staying silent. I loved spying on him.    Most people covered themselves up all the time. Not Da. He didn't care if you walked in on top of him. He was the same on the beach. When other people were wrestling under towels, he'd dry his hairy part to the heavens. He told me that the Fianna used to run around Ireland in the nude, over hills and through forests, and they wouldn't break a twig underfoot.    He took a square of paper and blew his nose with it. The Reillys of James Street, Rialto, Kilbarrack, and Raheny met a snotty end. He dropped the piece of paper into the bowl between his legs, and it landed on his thigh. - You stupid pig's mickey.    He whipped off another square and mopped up the Reillys. The Reynolds were next. He took about half the families in Dublin and got up to wipe his arse. He turned around to check his stools in the pan (he was a great believer in checking your stools), looked up, and saw me. He didn't flinch. - I want you to take the advertisement over to the Irish Press on Burgh Quay.    He placed the piece of paper in the hole where my face was. He pulled his trousers halfway up and fumbled in his pockets for money. He took out two half crowns and placed them in the hole. - You'll need to go on the bike. They close early on account of it being New Year's Eve. Hurry.    I put the advertisement and the money in my pocket. I ran into the house and got my coat. By the time I had it on, Da had the bike ready at the back door. I threw my leg over and sat on the saddle. I could feel the hard lump of a penny under the soft skin of my bum. Da gave me a push start.    I loved going on messages uptown. I loved the adventure. I loved discovering places and finding short cuts. I loved the oul' wans and the oul' fellas. I loved the statues and the buildings and the shops. I loved Dublin. I loved everything about Dublin. I wouldn't let anyone say a bad word about Dublin, especially country people. If Dublin was a woman, I'd marry her.    The route to Burgh Quay? Up Emerald Street, right into Sheriff Street, left into Commons Street, right onto North Wall Quay, left over Butt Bridge, right onto Burgh Quay, and there. Easy.    In Sheriff Street I stopped at Mattie's, the best sweet shop in Dublin. Lucky Lumps that were tuppence uptown were only a penny in Mattie's. He had four different kinds of licorice. He had sherbet sticks, loose rock, loose biscuits, penny packs of sweet cigarettes with red tips on them as if they were lighting, loose marshmallows, honeybee sweets six a penny, everlasting gobstoppers, nancy balls (aniseed balls if you wanted to be posh), nougat, macaroon, blackjack, and flash bars. The best of the sweets were Lucky Lumps. Soft, sticky pink sugar on the outside, and hard on the inside. If you were lucky there was a three penny bit waiting for you on the inside, and if you were less lucky you could get a certificate you could exchange for a free Lucky Lump. I looked in Mattie's window. There they were, staring back at me. Bull's-eyes. I'd forgotten about them. They looked delicious. I loved the way your whole mouth went black eating them. At the end of the day, though, they were only a sweet. Lucky Lumps were a sweet and a surprise.    I parked the bike outside and jumped down the three steps into the shop. I put the two half crowns and the penny on the counter and waited for Mattie. The bell tinkled, and he came out of the house part of the shop. - I want a Lucky Lump.    I ran back up the steps and out onto the street. I pointed out the one I wanted. I said a Hail Mary and went back in. Mattie held out the Lucky Lump. I went to pick up the money off the counter, and it was gone. I was just about to scream when Mattie produced the half crowns from behind his back. - Be careful where you leave your money, son    I took the money and squeezed it. I squeezed it till my hand hurt. I jumped on my bike and was in Commons Street before I realized I'd forgotten the Lucky Lump. I'd get it on the way back.    The girl in the Irish Press must have been going in for the Miss World Beauty Contest. She had more makeup on than anyone I'd ever seen. She read the ad. She seemed very satisfied with the wording because she purred to herself. She read it aloud. - Where do you live? - Seville Place. On the corner of Emerald Street. - That's very handy. Seville Place. Tell me, do you have any big brothers? - Yeah. Shea. He's bigger than me. He's thirteen.    Her face dropped. She started to write on an official-looking piece of paper. She looked up and smiled at me. - What age are you? - I'm ten.    She flicked the hair back from her neck. I could see where the makeup ended. She pushed the form toward me and asked me to sign it. She spoke like the parrot in Uncle George's pet shop. - Three insertions. Starting tomorrow. January first. Small ad in our accommodation to let. That'll be seven shillings, sixpence. Sign at the bottom.    I looked at her in despair. - It's five shillings. My Da counted the characters. - What characters? - The characters in the ad. - Now you pay the seven shillings, sixpence, or you piss off out of here. - I only have five shillings. - You only have all modern conveniences, or is that a lie, too? What are your bathroom facilities like? Are you deaf? - We have two toilets. - One not enough for you? Go home and get the extra half crown and don't be annoying me.    I looked down at the form. I put a line through the word location . It seemed to make sense. I wasn't sure anymore. I pushed it across to her. She counted the letters. She looked straight into my eyes when she was finished. She turned the form around on the counter and put a pen on it. She asked me to read it back to her. - Lodgings. Center city. Adjacent RC church. All modern conveniences. Phone 41966. - Sign at the bottom.    I signed it in my best writing. I handed over the two half crowns. She smiled at me. - Two toilets. How lucky can you get? I might just call.    I pedaled home like a madman. What would Da say if Miss World rang? We didn't even have a proper bath yet. Well, the bath was in position, but it wasn't connected. We still used the metal one in front of the fire on Saturday nights. That wouldn't do for lodgers. Definitely not for lodgers. I should have crossed out the telephone number. It wasn't easy when you were ten to make the right decision. I pulled on the brakes outside the Custom House and decided to go back. I'd take the ad out. Da might even appreciate getting the five shillings back. I was a fool. Miss World had the telephone number no matter what I did. She knew my big brother's name was Shea.    I turned the bike around and headed home for the second time. I hated Dublin. I hated everything about it. If Dublin was a football I'd kick it in the Liffey. I hated being ten. I looked at nothing on the way home. Not the Guinness boat, not the Liverpool boat, not the Isle of Man boat, nothing. All I could see in my mind was Miss World ringing our house and Da coming down from the phone with a beetroot face. - You've destroyed me, son, you've destroyed me with a dame!    I went into Mattie's. - Who died belonging to you? - I did.    I put the Lucky Lump in my pocket. How could I suck happiness now? I would never be happy again for the rest of my life, I knew that. * * * At home there was great excitement. A big box covered in brown paper stood in the middle of the table. Frankie, the baby, though not a real baby--he was three--was climbing on a chair trying to get to it. - I mant it.    My sister Ita, who was twelve, wasn't much bigger than Frankie. She was tiny for her age, but she was a dynamo. She pushed the box across the table away from him. - You can't have it, Frankie.    Frankie got down and raced around to the far side of the table and up onto another chair. Ita moved his chair away from the table. He was stuck in no-man's land. Ita moved all the other chairs as well. Now there were no chairs at the table. Frankie was flailing his arms about, grasping for a box that was miles out of reach. He looked pathetic. It made us all laugh. - I mant it.    Shea was sitting in the armchair by the fire. - You don't mant it, you want it. You can't have it till you learn to speak properly. - I ... I ... I ...    We all turned our eyes on him. Johnny, who was eight, crawled out from under the table where he'd been hiding but had now forgotten who it was he was hiding from. Johnny sang his encouragement to Frankie 'cos Johnny sang all the time. - You wa ... wa ... wa ... wa ... what? - I ... I ... I ... I ... want ...    The word was loud and clear. We all went silent. Then a cheer. - Hooray--hooray-- - Frankie said want-- - He said it perfectly--    Johnny stamped his feet and sang out in a chorus. - I want I want I want I want I want I want I want I want.    Frankie took it up. - I want I want I want I want I want I want I want I want.    They'd forgotten what they wanted. They were soldiers marching to war. Frankie nearly fell off the chair, but Ita caught him in time. She was special like that. She could see things that were going to happen. She was tiny because she was so sensitive. It was like she didn't want to take up too much room in the world because she wanted to leave space for others. The body of a child and the mind of someone twice her age. Da was disappointed she never saw who was going to win at the races. Ma said she had a gift that was not for material gain. Ita said it frightened her sometimes because she saw people who were going to die. Most people wanted to see into the future, but I looked at Ita sometimes, and I knew she was having a vision. She looked sad. I could see the tears at the back of her eyes. It made her beautiful, too. A doll with a human heart.    Ita lifted Frankie onto the floor, and he ran out to the scullery shouting. - Mammy, mammy, I mant the box on the table.    We all burst out laughing. Frankie started to cry. That made us laugh even more. He came back into the room shouting through his tears. - I mant it, I mant it, I mant it.    He lay down on the floor and started to kick his feet like a helicopter. No one could get near him. He got so bad it wasn't funny anymore. - What's in the box? I asked.    Ita looked at me. - Da won't say. - I know but I'm not saying.    Shea always knew things like that. Ma told him everything. He was Ma's favorite, and she never did anything to hide it. Shea always took Ma's part when she fought with Da. He was her little protector. She told him things she didn't even tell Da. Ma came in from the scullery with a big plate of buttered bread. The phone rang upstairs in the hall. - Answer that, Seamus.    Ma always gave him his full name. - If I do, they'll take my seat.    No one gave up the armchair that easy. `Specially not when it was freezing outside like it was today. It suddenly dawned on me that it might be Miss World ringing about the ad. I ran up and answered it. There was no voice at the other end. I knew it was her. - I'm sorry, we have no room.    There wasn't a breath. Nothing. Just someone listening. - We're full up.    I pressed button A. The phone came alive in my hand. A machine-gun laugh at the other end. That meant it was Uncle Paddy. Uncle Paddy was normal in every way except that he couldn't stop laughing. No, he could stop, but he didn't want to stop. To have a conversation with him, you had to laugh. If you didn't laugh, it looked like you were making fun of him. Paddy laughed before he said a word, in the middle of a word, and at the end of a word, depending on the sense and the sentence.    I held the phone away from my ear. - Is--    He chuckled. - Is your--    He sucked for air. - Is your Daddy--    He chuckled and he sucked. - Is your Daddy there?    He went into total convulsions. Hysterics. It was an ordinary sentence, but he made it sound like the funniest thing ever said. I knew he was going to be a few minutes laughing to himself. I read the instructions by the phone and laughed with him. 1. Lift receiver. 2. Insert coins. 3. Dial number. 4. Await reply. 5. Press button A. 6. To retrieve coins press button B.    Beside it Da had written "please comply." On the phone his brother Paddy had stopped laughing. - I think he's in the bookies', Uncle Paddy.    I knew he'd laugh at that. I read the instructions another three times. After about three minutes Paddy gave me a message for Da. - Tell your Da the aerial has landed.    It was all secretive and hush-hush. - The aerial has landed, over and out.    I replaced the receiver and pressed button B. Sometimes money came out. Nothing today. I jumped the four steps down to the kitchen door. Soon as I walked in, Ita looked at me. - That was Uncle Paddy, wasn't it?    I didn't answer her. - I knew. I knew it was him. - Yous heard him laughing down here.    I looked at Shea. He shook his head. I looked at Ita. It was the sad look. - I knew that was Paddy, just like I know that's a television set.    All eyes went to the box. - A television set?    No one dared disagree. Frankie got up on a chair to have a better look. - What's a tebibision, Mammy? - It's a cinema in your own home.     The aerial has landed. Now I understood. I said it out loud. Everyone turned and looked at me. I said it again, this time with a smile. * * * - Get the ladders out!    It was Da's favorite expression. When Da said it, you knew he was going up on the roof. It was his kingdom up there. On the roof, Da was king. - Get the ladders out.    As far back as I could remember, I was following him up ladders. I knew every blemish and paint stain on them. I knew each rung individually, the ones that had been repaired and the ones that needed repairing. The ones that escaped the frost and the ones that didn't. I knew the respect they deserved and the respect they must be given. - Get the ladders out.    "Get the ladders out" meant Da changed into his work clothes. Five days a week he wore a suit and tie to the booking office in the train station. Another three nights a week he worked at the greyhound track. Those were jobs he did for other people. What he did in his own kingdom was missionary work. It was Da securing the battlements.    His work clothes were hand-me-downs from Adam. There were two slits in the seat of his trousers so that his arse peeked through every time the wind blew. There were slits at the front where his knees came through. Front and back, there were two perfect creases from Ma's ironing skills. The only original part of the shirt was the collar, which had been turned at least twice. The tail was from a pair of pajamas, the back was the front of a vest, the right sleeve was blue and the left sleeve was kind of pink (but now looked black), none of the buttons matched, and only two of them closed. The jumper had no elbows and no back, only a front that looked like a baby's dribbler. His shoes had been brown once and were now colorless like the earth. The laces were white binder twine, saved from the bin months earlier. He wore two pairs of socks that were an insurance against foreign bodies inside the shoe.    The most important item was what went on the head. Da knew this from history, and he knew it from personal experience. He knew it stretching back to the Greeks and from them through the Romans, the Vikings, Cromwell, and down to the present day. Da knew that 80 percent of body heat disappears out of the top of your nut. You could wrap yourself in bear skins from the North to the South Pole, but without cover on top you might as well work in your nude.    It was snowing. A light snowfall. All over Dublin, people were getting ready to ring in the new year. Kids were trying to catch snowflakes in Seville Place, Emerald Street, and Sheriff Street. High up on a balcony a drunken man could be clearly heard singing a hymn to summer. He was praying for warm days and cold beer and something called "pretzels."    At four o'clock, Da said we'd be watching pictures from the BBC by five o'clock. Five o'clock in the morning, Uncle Paddy added, and the whole house fell about. I laughed so much the shepherd's pie from dinner came up my throat and into my mouth. I got such a fright I swallowed it straight back down.    It was half past eleven. The roof was like a scene from Mars. Da had rigged up his work light and had it hanging from the chimney stack. This cast huge shadows over the snow and along the terrace of roofs. Every time they moved the aerial, it seemed that a giant centipede was about to enter our house through the roof. As well as the work light there were improvised lanterns--candles set inside disused bean tins. They were all over the roof, and Da and Paddy used them to warm their frozen hands from time to time. They looked like zombies who'd been attacked by the Abominable Snowman. The drunken singer continued to croon in the distance. Fuck him and the days of summer. And double fuck him. They had been seven straight hours on the roof wrestling with the aerial. They were beaten men. They made another adjustment to the brackets on the chimney stack. It was the tenth time they'd altered them. They looked at each other and knew it was the final throw of the dice. Thy got a good footing and gripped the aerial between them. Slowly, gently, they lifted it toward the receiving slots. One false move, one unexpected gust of wind, and they'd sail clean off the roof.    I watched them from my perch at the top of the ladder. It was a long way up from the ground. Three stories. I was safe where I was. I watched the two brothers lift the aerial. They didn't speak a word. A word was a breath, and a breath could upset their balance. Until they had the pole in the socket holes, they were an accident waiting to happen. On the first try, they missed it altogether. They looked at each other, and I thought I heard Da say, - I love you, brother,    They went at it again, and it slotted in like they were a circus act. They pushed it straight up into the sky. Straight and true like a plumb line. They stood up, too, like they were first cousins of the aerial, like they were saluting its achievement by saluting their own. Uncle Paddy's laugh returned, and Da was humming along with the distant crooner.    In no time the coaxial cable from the aerial was lowered down the back wall, taken in through the kitchen window, and plugged into the back of the television set. The entire family sat in a big semicircle and stared at it. Ma was in the armchair by the fire with Frankie asleep in her arms. Johnny was under the table as usual, wide awake, hiding from someone. Uncle Paddy told Da to turn it on, and whatever way he said it, we were all in convulsions in seconds. We didn't need a television so long as Uncle Paddy was around. No one could stop. Then Uncle Paddy got all serious. - Come on, now, give your Daddy a chance.    Da reached out to turn it on. His hand was still blue with the cold. He couldn't grip the switch. He blew on his fingers and tried again. The click sounded like an explosion. A small dot appeared in the center of the screen. It was magic. The dot disappeared, and we all let out a sigh of disappointment. Just as quickly the whole screen lit up, and we all sighed again with elation. It was a picture of snow. It filled the screen. From top to bottom and from side to side. It was snow outside, and now it was snow inside, too. Frankie woke up and pointed at the television. - Look at the moon.    It was as if he'd had a vision in his sleep. Something in his brain had connected to something in the television. - Look at the moon.    Ma shushed Frankie and turned to Da. - You've done enough for one night. Leave it, Da.    He was so annoyed he didn't answer her. Never leave a job half done was one of his cardinal rules. Having risked his life and that of his brother, he was not about to abandon ship just yet. He'd prefer to float off the roof to his doom than leave a screen full of snow as his legacy to mankind.    He went out to the scullery, but it wasn't to drink tea. Whispers could be heard coming from it. We stared at the snow, pretending not to listen. Finally Da came back in, followed by Paddy. He took off his woolen cap and threw it in my lap. - Get that on, son, you're going up the aerial. * * * I knew not to look down. To look straight ahead, like Da told me. I was shaking with fear. I remember the Greek boy. He didn't do what he was told and flew too near the sun. Disaster. Da and Paddy put a hand each under the cheeks of my bum and pushed me skyward. I reached with my arms and gripped with my feet. Now they put a hand each under the soles of my feet and gave me another push toward the stars. Each time I slid up those few feet, the aerial swayed gently under my weight. That was the worst part, worse than the snow going up my nose and into my mouth. I felt the fishbone aerial against the top of my head. I wanted to look down and see how far up I was, but I gritted my teeth and kept my eyes straight ahead. - Now son, listen to me. Very gently reach up your hand, do you understand me?    I had never heard such emotion in his voice. I felt wrapped up in his words even though I was in the sky. He sounded like a different father. A father who didn't care about systems, or logic, or the old Greeks, who only cared about me, how I was and how I was going to be. - Reach up your hand and turn the aerial toward England.    I'd have flown to England if he'd asked me. I reached up my hand, and the aerial moved voluntarily. I turned it without looking. Then I stopped. - Where's England, Da? - Toward the river. Turn it toward the Liffey and hold it there.    I turned it in a straight line that connected Howth and Dun Laoghaire. Da sent the message down the line of communication he'd established. - Have we a picture?    Johnny at the top of the ladder shouted down to Ita at the bottom. - Have we a picture?    Ita ran in to Shea, who was in charge of the tuning. - Have we a picture?    Shea turned the button fully one way, then the other. Word came back up the line. - Snow. - Snow. - Snow. - Snow.    The light on the roof changed. Out of the corner of my eye I could see Paddy's baldhead as he took Da's worklight off the hook on the chimney stack. He pointed with it as if it was a giant finger. Across the terrace of roofs. - There's your problem. There's your problem, right there. The church is blocking your signal. The church stands directly between you and a perfect picture.    Da took the light from him and looked for himself. - Saint Laurence O'Toole, bastard. That you were ever born, you pig's mickey.    Paddy reached across and took the light back. - The church may be blocking your signal, but it has to go somewhere. Coming from England, it's going to bounce over there.    Paddy turned the light northward. Da saw it immediately. - It's going to hit them houses and bounce over there.    Paddy turned the light southward. - It's going to re-form over there, do a little jazz dance, and work its way in to us from the direct opposite side.    The two of them shouted at me with one voice. - Turn it around, son, turn it around.    I turned the aerial in the complete opposite direction. Word went down the line. Word came up the line. - There's a picture! - There's a picture! - There's a picture! - There's a picture!    I fumbled in my pocket for a spanner and felt the Lucky Lump. I'd forgotten all about it. I tightened the nut that held the fishbone aerial in position.    Half an hour into 1960 we all sat staring at the television. It felt very different from 1959. The sound was perfect. A man was describing "traditional revelry" in Trafalgar Square. There was definitely something on the screen. Outlines that looked like human beings. I went right up close, but all I could see were dots and lines. Paddy touched something at the back of the set, and there it was--a perfect picture. Well, nearly perfect. Lots of snow, but a definite picture. We all clapped. It was a woman on a horse. She looked majestic. She looked regal. A big silver sword in her hand. - What do we need that woman for?    Ma was off. We tried to shush her. - I won't be shushed in my own home. Not for that woman and her fat horse. She's not the queen of this country, let me tell you, television or no television.    Ma left the room with Frankie asleep in her arms. Da threw his eyes to heaven. - Dames!    We stayed glued to the television. The music blared out, and the queen inspected the guard. Da and Paddy stood behind us. Their father had fought in 1916, and here they were, stealing pictures from London.    I popped the Lucky Lump in my mouth and started to suck. I sucked as hard and fast as I could. I won nothing, but it felt like it had been one of the luckiest days of my life. Maybe it was an omen. I couldn't wait for the rest of the sixties to begin. Copyright © 1999 Peter Sheridan. All rights reserved.