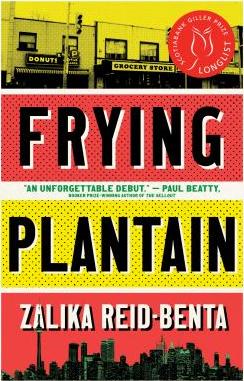

Frying plantain : stories

Kara Davis is a girl caught in the middle -- of her Canadian nationality and her desire to be a "true" Jamaican, of her mother and grandmother's rages and life lessons, of having to avoid being thought of as too "faas" or too "quiet" or too "bold" or too "soft." Set in "Little Jamaica," Toronto's Eglinton West neighbourhood, Kara moves from girlhood to the threshold of adulthood, from elementary school to high school graduation, in these twelve interconnected stories. We see her on a visit to Jamaica, startled by the sight of a severed pig's head in her great aunt's freezer; in junior high, the victim of a devastating prank by her closest friends; and as a teenager in and out of her grandmother's house, trying to cope with the ongoing battles between her unyielding grandparents.

Browse Related Items

- ISBN: 9781487005344

- Physical Description 257 pages ; 21 cm

- Publisher [Place of publication not identified] : [publisher not identified], 2019.

Additional Information