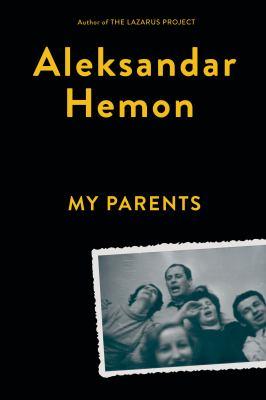

My parents ; This does not belong to you

Browse Related Items

| Genre |

| Autobiographies. |

- ISBN: 9780735238381

- Physical Description 168, 182 pages : illustrations ; 24 cm

- Publisher [Place of publication not identified] : [publisher not identified], 2019.

Content descriptions

| General Note: | Texts printed back to back and inverted, each with its own title page. |

| Formatted Contents Note: | My parents -- This does not belong to you. |

Additional Information

My Parents / This Does Not Belong to You

Click an element below to view details:

Excerpt

My Parents / This Does Not Belong to You

The story goes that my mother's grandfather Zivko was going back home on his horse-drawn sleigh after a winter night of drinking and gambling, when he ran into a couple of terrifying giants blocking the path. He owned a lot of land, a provisions store, even had servants; he was rich and therefore imperiou sand arrogant. He determined that the giants would destroy him if he stopped, so he stood up on his sleigh, whipped forth the horses, and rushed at the creatures, who stepped aside to let him through. His daughter, Ruza, married my grandfather Stjepan ZivkoviÄ, who would never run into a giant and whose family was not rich at all. The marriage was not arranged, which was uncommon in the northeast Bosnia* at the time (1921 or so), when marital bliss was inseparable from the goods and properties transacted between the bride and groom's families. Mama believes that love was involved: Ruza's father disowned her for going against his wishes. Ruza and Stjepan would have seven kids; my mother, Andja, born in 1937, was the youngest. When she was four, Mama's older brother Zivan was playing a game with his friends that involved smacking a piece of wood with a stick (klis). The piece of wood hit him in the belly; he was full after lunch; his stomach ruptured and he died. The story doesn't quite add up--the piece of wood couldn't have been that heavy--but that was what my mother was told. When sorrow comes it comes not as single spies, but in battalions: right around the time of Zivan's death, World War Two entered Yugoslavia byway of the invading Germans. Mama's oldest brother Bogdan was nineteen when he joined the partisan resistance movement. Mama remembers that whenever she woke up in the middle of the night during the war years, she'd find Ruza awake, worrying about her eldest son, swaying to and fro on her bed like a Hasid. The war was complicated in Bosnia, as all its wars have always been, as all wars always are. In addition to the Germans, Tito's partisans had to fight against the royalist Serb forces--the  Äetniks --who openly collaborated with the ocuppying forces, busying themselves mainly with massacring Muslims. My mother's family is ethnically Serb, and the area where they lived--the village called Brodac near the town of Bijeljina--was solid  Äetnik  territory. Much of Ruza's family supported the Äetniks  too, by a kind of default that comes with being rich and arrogant. Stjepan, on the other hand, would not have any of that, and not only because his eldest son was a partisan--he was also just a decent man. The  Äetniks  would occasionally come by to look for Bogdan, and when they couldn't find him they'd harass Stjepan. He once hid, in a pile of manure, a box of ammo air- dropped by the Allies in order to deliver it to the partisans. But someone informed the Äetniks , who beat my grandfather into a pulp, demanding to know where the ammo was. He told them nothing; they took him to a detention camp and would've likely slit his throat if Ruza's family hadn't intervened; he would subsequently be under house arrest for six months. Another time, toward the end of the war, Stjepan gave his only horse to a wounded young partisan on the run. The young partisan promised he would return the horse; he never did, but Stjepan would never regret helping a man in trouble. He must have imagined that someone else, somewhere else, could in the same way decide to help his son. My uncle Bogdan did manage to survive the war, and was in the unit that fought at the Sremski Front, in the difficult battle that ensured the defeat of the German and collaborator forces and the liberation of Belgrade. As a machine gunner he was always a prime target; he received a bullet in his chest, while two of his assistants were shot dead next to him. A lung had to be removed, and he would never be entirely healthy again. Nor would Ruza ever sleep again, at least not until her death. Mama was a child when the war ended, but she would never talk about being scared or traumatized by it. Neither did she tell any childhood stories: there were few adventures, she had few anima lor human friends, she did not even get into trouble with her siblings. Narratively speaking, Mama did not have a childhood. First she was in the war, the littlest of the kids, and then, with the end of the calamity, a moot but exciting future opened up for her and she had to leave her childhood behind. In 1948, when she was merely eleven, she moved to attend middle school in Bijeljina, five miles and very far away from her village. She lived in a rented room, taking a train back home every weekend. She stayed in Bijeljina through her high school years, graduating with good grades in 1957 from--and this is only for the name--Drzavna realna gimnazija Filip VisnjiÄ. Then, as ever, she was a devout and conscientious student. In 1957, she went to college in Belgrade, the capital and the biggest city in Yugoslavia, some eighty miles and a century away from Brodac. She at first resided with three other young women in a dorm room in Studentski grad (the Student City). She subsisted on a modest stipend, with little money and few possessions. But she had fun, and still likes to reminisce about the beauty of communal youth, about the ethos of sharing everything--meals, clothes, experience--about the sense that, despite manifest poverty, there was nothing lacking. There were dances ( igranka ) at the university cafeteria, featuring one Mirko Souc and his rock 'n' roll band; she would sometimes go to two dances in a single night. U.S. movies played in the theaters, if with a several years' delay. Esther William sreigned; Three Coins in the Fountain was a blockbuster, and the song from the movie was enthusiastically sung by the youth, in their, shall we say, limited English. Kaubojski filmovi (cowboy films) in general, and John Wayne in particular, were beloved. To this day, Mama--ever prone to passing out before a TV--stays awake for Rio Grande or Rio Bravo or Red River . Soviet movie scould be seen too: The Cranes Are Flying , a post-Stalinist Soviet film about love and war (and rape), would make an entire theater sob in unison. They also watched Yugoslav movies, as the country's cinema was going through one of its golden periods. The plot of Ljubav i moda (Love and Fashion) , for instance, revolved around the young people organizing a fashion show to fund their gliding club. The movie opens with a tracking shot of a hip young woman riding a Vespa on the streets of Belgrade, not exactly crowded with cars, while a sugary pop song ( slager ) warns us that a young man might be coming along. Unsurprisingly, she runs into one at a streetlight; in no time he tells her that she should be in the kitchen and not on the Vespa, calling her a "motorized schizo-girl"; she calls him a brute, and love is as imminent as fashion. In the photos from that time, my mother often looks like the girl on the Vespa: the balloon skirt, bobby socks, and a beehive hairdo. Indeed, she remembers watching the shoot for Ljubav i moda . When I first saw the movie, I looked for her face in the crowd. The movie features not only young, well-dressed women and men laughing, flying gliders, and addressing one another as "comrade," but also Yugoslav pop stars arbitrarily breakin gout into badly lip-synced songs, one of them containing the immortal line: "Because fashion is the whipping cream and love is the ice cream" (" Jer moda to je slag, a ljubav sladoled "). Among those songs was "Devojko mala," which would a generation later be unironically covered by a hip band (VIS Idoli) I loved and listened to. Around that time, in the eighties, I had great interest in the music and films from my parents' student days, and their youth appeared to me cool to the point of nostalgia. In contrast, I don't think that Mama ever longed to have lived her parents' lives--by the time of Love and Fashion , the gap between the generations was far too wide. My discovery of her cool past allowed for a cultural continuity between us; we could now have a common referential field. I wanted to have lived through such a youth, was envious ofthe experience of unbridled optimism, joy, love, and fashion. Mama would often marvel at the fact that I listened to the music of her generation, to what she called "our music," but even when I was young, I was never as young as she had once been. Excerpted from My Parents / This Does Not Belong to You by Aleksandar Hemon All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.