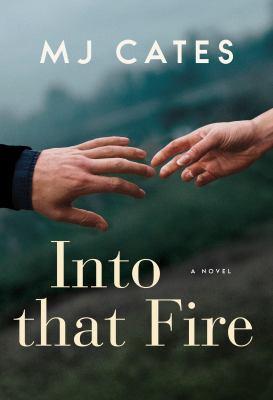

Into that fire : a novel

Imogen is going to hurt Quentin, and she can't bear it. He has been her only friend and confidante during her time at medical school in Chicago, but she's realized he wants more than friendship and she needs to tell him she does not share his feelings. Unlike most other well-brought-up young women in 1916, Imogen does not want to be a wife. Instead, she wants to become one of the country's first female psychiatrists, and she has just accepted a residency at the world-leading Phipps Clinic in Baltimore that will take her away from her best friend. Quentin is shattered by her rejection, and heads across the border to sign up with the Canadian Expeditionary Force and go to war; he tells her, in one of his only cruel moments, that he does not have the nerve to kill himself so he'll let the Germans do the job for him. While Quentin encounters unthinkable horrors on the battlefields, Imogen faces her own struggles, whether it is the sexism that constrains her or the barbaric practices that are accepted as treatments and "cures" for mentally ill patients. When she receives the news that Quentin has been killed, she falls into a bleak depression, which reveals to her what she has sacrificed to pursue her dream. Emerging from her own darkness, Imogen finds a deeper empathy for her patients and even more passion to find real ways to help them. Which sets her on a collision course with the powers-that-be. And eventually leads her to a further reckoning with Quentin. Into That Fire is an engrossing novel about a remarkable woman with a haunted past trying to carve out a winning future for herself. At its heart, it's a love story about uncovering one's true desires.

Browse Related Items

- ISBN: 9780735273764

- Physical Description 419 pages ; 24 cm

- Publisher [Place of publication not identified] : [publisher not identified], 2019.