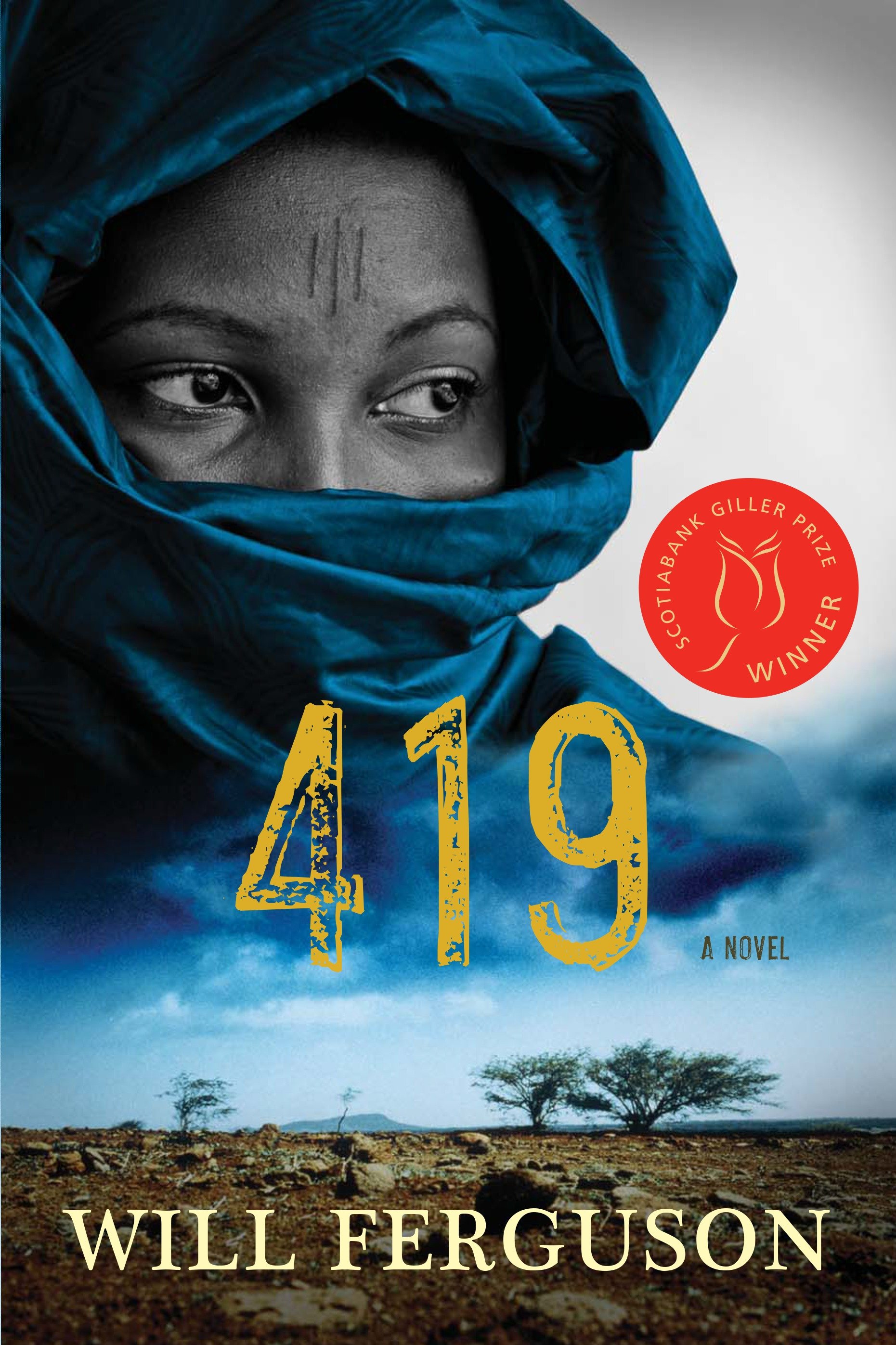

419

-- A car tumbles down a snowy ravine. Accident or suicide? On the other side of the world, a young woman walks out of a sandstorm in sub-Saharan Africa. In the labyrinth of the Niger Delta, a young boy learns to survive by navigating through the gas flares and oil spills of a ruined landscape. In the seething heat of Lagos City, a criminal cartel scours the internet looking for victims. Lives intersect, worlds collide, a family falls apart. And it all begins with a single email: 'Dear Sir, I am the son of an exiled Nigerian diplomat, and I need your help ...' 419 takes readers behind the scene of the world's most insidious internet scam. When Laura's father gets caught up in one such swindle and pays with his life, she is forced to leave the comfort of North America to make a journey deep into the dangerous back streets and alleyways of the Lagos underworld to confront her father's killer. What she finds there will change her life forever ... From the internationally bestselling travel writer Will Ferguson, author of Happiness'¢ and Spanish Fly, comes a novel both epic in its sweep and intimate in its portrayal of human suffering. It's a story of love in a time of darkness, of one woman's search for redemption, and of a young boy who will triumph above it all.

Browse Related Items

| Genre |

| Electronic books. |

- ISBN: 9780143188049

- Physical Description 1 online resource 416 pages

- Publisher [Place of publication not identified] : Penguin Canada, 2012.

Content descriptions

| General Note: | Electronic book. GMD: electronic resource. |

| Reproduction Note: | Electronic reproduction. [S.l.] Penguin Canada 2012 Available via World Wide Web. |

| System Details Note: | Format: Adobe EPUB Requires: cloudLibrary (file size: 374.0 KB) |

Additional Information