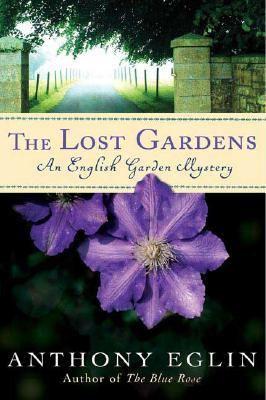

The lost gardens : an English garden mystery

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Community Centre | Available |

Browse Related Items

| Subject |

| Rose culture > Fiction. Gardeners > Fiction. Gardening > Fiction. England > Fiction. |

| Genre |

| Detective and mystery fiction. Fiction. |

- ISBN: 0312328729

- ISBN: 9780312328726

- Physical Description 294 pages

- Edition 1st U.S. ed.

- Publisher New York : St. Martin's Minotaur, 2006.

- Copyright ©2005

Content descriptions

| General Note: | "Thomas Dunne Books." |

| Bibliography, etc. Note: | Includes bibliographical references (page 293). |

| Immediate Source of Acquisition Note: | LSC 31.95 |

Additional Information

The Lost Gardens : An English Garden Mystery

Click an element below to view details:

Excerpt

The Lost Gardens : An English Garden Mystery

Chapter One Somerset, 2003 The clang of metal on metal resounded off the walls of the old stone house, echoing across the lawns to be lost in the dense forest beyond. 'Doctor!' Lawrence Kingston brought the sledgehammer down on the iron stake one more time. 'Doctor!' He looked up to see the carrot-haired figure of his foreman, Jack Harris, approaching. Leaning the sledgehammer against his leg he wiped his brow with the back of his hand. He was about to take a rest anyway. For the last twenty minutes he had been surveying, driving in stakes on the top lawn--one of three football-field-size levels that stepped down from the back of the big house. Once mown and rolled twice a month to look like green carpeting, they were now a waist-high tangle of weeds. 'Need you to come and take a look at something,' Jack said, nodding back over his shoulder. 'Be right there.' Kingston picked up the survey maps, put them in his canvas bag and walked over to join Jack. Was it good or bad news? From the look on Jack's face, Kingston couldn't tell. 'What you got then?' he asked. Jack smiled. 'You'll see in a minute.' With nothing further said, they took off. Soon they reached a clearing some five hundred yards from the house. It was in one of the most overgrown sections of the 'Jungle', as it was now nicknamed. Nearby, to the staccato whine of chainsaw and thwack of axe blade on wood, Jack's crew of three was chopping up the fallen trees and cutting down the dead ones, many of which were supported by their less tipsy neighbours. Wood-smoke from their bonfire was thick in the still air. When Jack and Kingston arrived, the men stopped work and gathered around. Jack said nothing, waiting for Kingston's reaction. Facing them, built partway into a vertical limestone crag, was the façade of what appeared to be a small chapel. Off to one side was a house-high tangle of ivy, brambles and vines that had been cut and ripped away from its walls by Jack's crew. 'It was completely covered,' said Jack. 'You could've walked by here a hundred times and never known it was there. Three feet thick it was.' 'Amazing,' Kingston muttered, walking up to the blackened oak door, touching the rubblestone surround. Fern-edged trails like giant snail tracks tattooed the wall where the ivy had been tugged away. On either side of the door two identical stained glass windows displayed griffins. The glass was filthy but intact. 'Did you go inside?' asked Kingston. 'No, I thought it best to wait for you.' 'Let's take a look then.' Gripping the large iron door handle, Kingston turned the key and the door swung open, hinges creaking. Why the key had been left in the door was something that he would ponder later. He was too excited to worry about it now. Sufficient light filtered through the open door for them to make out the interior. The space was no more than twenty-five feet wide and about forty feet long. The walls were wood and plaster, the ceiling simply raftered. For a chapel, and that's surely what it was, Kingston was surprised at the absence of ecclesiastical artifacts and trappings. The only ornamentation apparent was the handsome bronze sconces, four on each of the two long walls, none holding candles. A central flagstone aisle ending at a pulpit was flanked on either side by eight rows of simple wooden pews. The pulpit was panelled with turned balusters. But Kingston's eyes were not on the pulpit. He was looking at what was beyond. As he walked farther down the aisle he could now see clearly what had seized his attention. Behind the pulpit alongside a small baptismal font was a large stone circular well about five feet in diameter. It looked out of keeping with the rest of the interior. He went up and rested his hand on the cold stone. 'Well, I'll be damned,' he said, turning to Jack. 'I bet this was originally a healing well.' 'A healing well?' 'Right,' he said, leaning over the waist-high ledge, peering down into the inky darkness. 'They go back to Celtic times and beyond, long before the Romans came. I'm told there are quite a few around here.' His voice echoed around the stark walls of the chapel. 'The waters are believed to have healing powers. In the Middle Ages wells were sanctified and frequented by pilgrims.' One of Jack's crew had followed them into the chapel. 'What do the waters heal?' he asked. 'Apparently just about anything ailing you--from a hangnail to a heart condition. Skin complaints, asthma, epilepsy, stomach ailments, you name it--even paralysis! Mental as well as physical, so legend has it.' Kingston stepped back, reached into his pocket and took out a coin. Dropping it into the well, he counted under his breath. One . . . two . . . on three, he heard the plop of the coin hitting water. 'Deep, by the sound of it.' He turned and cast his eyes around the low ceiling. 'Tomorrow, let's rig up some lights in here, Jack, and we'll show it to Jamie. She has her own place of worship now.' Jamie Gibson, an American, was the new owner of Wickersham Priory, the estate on which they were all working. Her project, both ambitious and expensive, was aimed at restoring the ten-acre gardens that had fallen into decay after decades of neglect. As he turned to go, something on the flagstones caught his eye; a slight glint, nothing more. He stooped to look closer. It was a coin. A few feet away there was another, then a third. Picking them up, he examined them in the palm of his hand. One was a shilling, dated 1963. A six-pence was dated 1959, as was another shilling. He turned to Jack, who was about to walk off. 'Jack, how long would you say this place has been buried in that ivy?' Jack thought for a moment. 'I dunno,' he said. 'Bloody long time, by the looks of it. You'd know better than me--why?' 'Just curious, that's all.' By eight o'clock the next morning Jack and his men had set up a battery-powered lighting rig with two floodlights clamped to a vertical rod mounted on a tripod. Over the wellhead they had constructed a makeshift pulley with a rope tied to the handle of a galvanized bucket. Shortly after eight fifteen Kingston and Jamie joined them. The bucket, weighted with a rock, was lowered into the well. It was some time before it reached the bottom. Huddled around the wellhead in the chill air, the small group watched silently as two of Jack's men began pulling hand-over-hand on the pulley rope to bring the bucket up from the bottom of the well. At last it broke the surface and they all peered over the stone ledge as it jerked and scraped its way up the last slimy ten feet--the sound echoing around the small space, misshapen shadows dancing against the white walls from the blaze of two halogen floodlights. Sloshing water as it was lifted over the stone surround, the bucket was lowered to the floor. Jack walked over and up-ended its contents, splashing them on to the flagstones. On his haunches, he shoved the rock aside and examined the fragments of whitish material that had spilled out with the last ooze of well water and black sludge. 'Looks like we got ourselves some animal bones, doctor,' he said. 'Rat--squirrel maybe.' Kingston walked over and knelt by the upturned bucket, poking the skeletal remains with his finger. He glanced at Jack. 'Can one of your chaps find a bag or a cloth that we can wrap these in?' 'Sure. Why?' 'Because this was no animal. It's what's left of a human hand.' The next day, in response to Kingston's phone call, Detective Chief Inspector Chadwick and Sergeant Eldridge from Taunton police arrived at Wickersham in an unmarked car. They were accompanied by a van with personnel from Avon and Somerset Constabulary Underwater Search Unit. Sitting in the third row of the pews, Jamie, Kingston and the chief inspector watched as the well area was cordoned off with blue and white tape and the scene photographed with a 35mm still camera, then videotaped. Soon the underwater search diver was lowered into the well. Three minutes passed. The diver had been submerged longer than any of them had anticipated. Conversation had ceased and all eyes were now on the steel hawser that dangled from a new pulley the police had rigged over the wellhead. Suddenly it jerked. He was on his way up. Everyone watched with anticipation as the diver was lifted out. He snapped open his buoyancy vest and swung the scuba tank to the floor. Gripping his mask with both hands, he eased it up, resting it on the slick hood on his forehead, blinking his eyes to adjust to the floodlights. By the time he had removed the mouthpiece and tugged off his gloves there was a puddle of water at his feet. Those in the pews waited on his words. 'Bloody dark down there,' he said. 'Bloody cramped, too.' Though his words were meant for Inspector Chadwick who was standing next to him, his voice echoed off the bare walls of the chapel for all to hear. 'Anything interesting, Terry?' Chadwick asked. 'If you call bones interesting, sir,' he said, peeling off his hood, waggling a finger in his ear and cocking his head to one side. 'The doctor was right. There's what's left of a body down there. Mostly bones.' 'No soft tissue, ligaments, clothing?' 'Just a skeleton by the looks of it.' An hour and a half later in the living room at Wickersham Priory Lawrence Kingston and Jamie sat discussing the grisly discovery. Between them on the coffee table was a disarray of china cups and saucers, a cosy-covered teapot, cake plates and crumpled napkins--the remains of their tea. The DCI and sergeant had departed a couple of minutes earlier, having spent the best part of an hour asking questions about the events leading up to the discovery of the bones. 'I must say, your policemen are polite,' said Jamie, starting to stack the china. Kingston pulled on his earlobe--a quirky habit whenever he was lost in thought--and nodded but made no comment. Jamie paused, fingers on the handle of the china teapot. 'Can you get DNA from bones?' 'Certainly,' Kingston replied. 'Though I believe it might be difficult coaxing DNA from the bones if they've been down there for many years, which appears to be the case.' Jamie got up, went to the sideboard to retrieve the tea tray. Kingston looked down at the table, speaking more to himself than to her. 'The inspector's probably right. I doubt seriously that we'll ever know who the poor soul was. Dental charts a remote possibility, I suppose.' She looked over her shoulder. 'How on earth would you go about matching someone's teeth if they've been dead for as long as the inspector suggests?' Kingston smiled. 'Not easy.' Jamie faked a shiver. 'I suppose there were teeth? It's all a bit too gross for me.' 'I'm sure there were. And you're right, the accident or murder--whichever--could have taken place centuries ago.' 'Before this house was built?' 'A possibility.' He rubbed his chin, thinking. Jamie screwed up her face. 'I hope you're right. I can live with a medieval family skeleton in the closet but it's another matter entirely if it took place more recently. Know what I mean?' Kingston laughed, got up from the chair. 'I wouldn't lose any sleep over it, Jamie. Like the inspector said, we'll probably never know.' 'Will they know whether it's a man or a woman?' 'They will, quite easily.' Kingston had adopted a professorial stance, hands clasped behind his back. 'They'll determine that from the ischium-pubis index. Height too,' he added, starting to pace the room. 'That's deduced from the length of the long bones in the arms and legs. Hadden and another forensic anthropologist, whose name escapes me, developed that formula.' Jamie's eyebrows shot up. 'God! How come you know all this?' Kingston smiled. 'Spent a couple of years in med school when you were just a twinkle in your father's eye, my dear.' 'Really? Why did you give it up?' Kingston grinned like a little boy who'd just landed his first fish. 'As the surgeon said, "I just wasn't cut out for it!' " 'Come on, Lawrence, be serious.' Kingston snapped his fingers. 'Dapertuis. Professor Dapertuis. That was the other chap's name. Oh--and one other thing--they'll also be able to determine, within reason, the age of the victim at the time of death.' 'What about how long he or she's been down there?' 'That can present a problem. The longer those bones have been down there, the more difficult it will be for the pathologist to determine the time since death. Damn. I forgot to ask the inspector the rate of decomposition that bones undergo after submersion in water.' He shook his head, frowning. 'What am I thinking of? Chadwick wouldn't know that,' he muttered to himself. Jamie picked up the loaded tray and started to make for the door. 'Anything I can get you, Lawrence?' Kingston sighed. 'Thanks, no. I think we should call it a day.' He studied Detective Chief Inspector Chadwick's card one more time, then put it in his shirt pocket. 'Get back to more pleasant things like gardens and flowers.' Straightening up after ducking under the low beam, Kingston closed the cottage door behind him. Thatched with honey-coloured stone walls, the cottage had been built over two hundred years ago to house labourers on the estate. Jamie had furnished it in a Laura Ashley style--a bit dainty for Kingston's taste but appropriate and comfortable. It was now his home from home while he worked with Jamie restoring the gardens at Wickersham. He picked up The Times and a pencil from the Welsh dresser, went across the room and sank into the sofa. The paper was already folded to the Saturday Jumbo crossword puzzle. He placed it on his lap and put on his glasses, ready to pick up where he'd left off the night before. Three days now and only half the answers pencilled in. Far off his usual pace. Considering that he'd been doing the mind-bending cryptic for Lord knows how many years, it was to be expected that once in a while he would be stumped. He read the 49 across clue for the third time: One's right up the pole, as the mad may be--8 letters.* For several moments he looked up at the misshapen timber beam that ran across the centre of the ceiling, the eraser end of the pencil resting on his lower lip. 'Bugger,' he said, finally, placing the paper back in his lap. He simply couldn't concentrate. His thoughts kept returning to the well, the skeleton and the coins, trying to picture what might have taken place there. He put the paper on the coffee table and stretched out, propping a pillow under his head. Once again the nagging feeling returned: that it could have been a big mistake on his part to become involved in Jamie's venture. It was too late now, though. He closed his eyes and thought back to that evening when she had first called him. Copyright (c) 2005 by Anthony Eglin Excerpted from The Lost Gardens: An English Garden Mystery by Anthony Eglin All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.