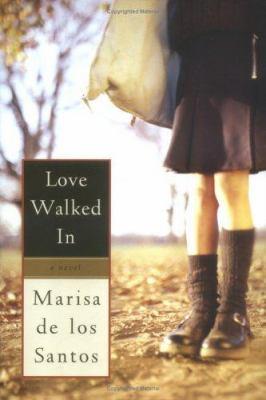

Love walked in : a novel

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Victoria | Available |

Browse Related Items

- ISBN: 0525949178

- Physical Description 307 pages

- Publisher New York : Dutton, [2006]

- Copyright ©2005

Content descriptions

| Immediate Source of Acquisition Note: | LSC 33.00 |

Additional Information

Love Walked In

Click an element below to view details:

Excerpt

Love Walked In

1 Cornelia My life-my real life-started when a man walked into it, a handsome stranger in a perfectly cut suit, and, yes, I know how that sounds. My friend Linny would snort and convey the kind of multipronged disgust I rely on her to convey. One prong of feminist disgust at the whole idea of a man changing a woman's life, even though, as things turned out, the man himself was more the harbinger of change than the change itself. Another prong of disgust for the inaccuracy of saying my life began after thirty-one years of living it. And the final prong being a kind of general disgust for the way people turn moments in their lives into movie moments. I do this more than I should, I'll give her that, but there was something backlit and sudden about his walking through the door of the café I managed. If the floor had been bare and not covered with tables, chairs, people, and dogs, the autumnal late-morning sun would have slung his narrow shadow dramatically across the floor in a real Orson Welles shot. But Linny can jab me with her three-pronged disgust fork all she wants, and I'd still say that my life started on that October morning when a man walked through the door. It was an ordinary day-palpably ordinary, if that makes any sense, like it was asserting its smooth usualness. A Saturday, loud, smoke already piling up and hovering like weather over me and the customers in Café Dora. I sat where I always sat when I wasn't waiting on someone-on a high stool behind the counter-and I watched Hayes and Jose play chess. Everyone said they were good players. They themselves said they were. "Not prodigy good," said Hayes. "Not Russian, Deep-freakin'-Blue-playing good. But hell." Hayes was from Texas and wrote the wine column for the Philadelphia Inquirer. He liked to swear in offbeat ways, liked to walk in, turn a chair around backward with a bang, and straddle it. As I watched, Jose lifted his shaggy head, gave Hayes a liquid-eyed, sorrowful look, and moved a chess piece from one square to another. I don't know the game well, but whatever Jose had done, it must have been something, because Hayes tossed back his head and hooted, "Hot damn, boy! You pulled that one right out of your ass!" Hayes looked at me with a wry smile and a genial cowboy twinkle in his eye, and I lifted one corner of my mouth in a kind of rueful facial shrug. "What can you do?" my face said. But don't get attached to Hayes. As he was already in the room, he's obviously not the man who walked into it bearing the new life on his shoulders, and he doesn't finally figure into this story much. Not sure why I started with Hayes, except that in lots of ways he's a neat little embodiment of the old life: a self-invented, smartish, semialluring wine snob disguised as a cowboy, not un- nice, with fairly amusing comments tripping off his tongue and probably a real person under there somewhere, but possibly not. In college, I read Piers Plowman in which this man Will goes on a journey and runs into characters like Holy Church and Gluttony. Think of Hayes as a character like that: Typical-Denizen-of-Cornelia's-Old-Life. I've always found allegories kind of comforting. When you encounter people named Liar and Abstinence, you might not be crazy about them, but you know exactly what you're getting into. Another regular, Phaedra, made her entrance, all blowsy auburn curls, leather pants, and nursing-mother breasts, and tugging a giant black pram behind her-one of those English nanny prams with high, white rubber tires. Five people jumped up and nearly cracked one another's skulls trying to hold the door open for her. Phaedra directed a beseeching look at the couple sitting at the table nearest the door, a look that turned out to be unnecessary. The man and woman were already hustling up their cappuccinos, jackets, camera bags, and backpacks on metal frames, not minding a bit. "Cornelia!" Phaedra sang at me across the room in just the sort of musical voice you'd expect to come out of her mouth. "Could you? Café au lait? Loads of sugar? And something sinful!" We don't have table service. Phaedra made a helpless, sighing gesture with her shoulders and her long hands, indicating her child, her exhaustion, the whole ancient weight of motherhood. Phaedra was a pain. But Allegra was a different story. Bearing the coffee and a croissant, I came out from behind my counter and made my zigzag way around tables and dogs for the sake of Phaedra's baby, Allegra. And there she was, wrapped in a leopard-print blanket, just waking up. A blue-eyed, translucent, bewitching witch of a baby, fresh as new bread in that smoky room. Allegra resembled Phaedra, same white skin, same glorious Carole Lombard forehead, but with carrot-orange hair that flew out in all directions. I waited for the pang; the pang came. I never saw Allegra without wanting to touch her, specifically to sleep with her in the crook of my right arm. I put the croissant and the coffee in front of Phaedra, then cradled my elbows with my hands. Allegra was asleep and making nursing motions with her mouth because what else would babies dream about? "Face it. You want one," said Phaedra. With effort, I shifted my gaze from gorgeous child to gorgeous pain-in-the-ass mother. "See that?" said Phaedra. "You had to literally drag your eyes away from her." Ouch, I thought, and then sat down to talk for a minute, Phaedra's misuse of the word "literally" having created a warm spot in my heart, tiny but large enough to prompt a five- minute conversation. "How's business?" I asked. Phaedra was a jewelry designer. "Not good. I'm starting to think people just don't get it," said Phaedra. Her signature pieces, or what would be her signature pieces if anyone bought and wore them, were made out of sea glass and platinum, a juxtaposition of the ordinary and extraordinary, Phaedra claimed, that forced one to rethink one's perceptions of "value" and "preciousness." Maybe people didn't get it. Or maybe they got it but didn't feel sufficiently moved to shell out eight hundred dollars for a bracelet made of old Heineken bottles. Phaedra lifted her coffee to her lips, eyeing me brightly through the steam. "Cornelia, what if you wore some of the pieces in the café, just to generate in-ter-est?" Her tone suggested the idea had just popped into her head. In fact, this was the third time she'd asked. "I can't wear jewelry at work," I said, not elaborating but rolling my eyes in a way I hoped suggested some unseen powers-that-be who hovered over me, forbidding jewelry. The truth was that I never wore jewelry anywhere, ever. I'm five feet tall and built like a preteen, eighty-five pounds soaking wet, as my father says, and my fear is that, given my smallness, jewelry will make me look like a geegaw or doodad, a spangly ornament to hang on a tree. It's a shame, too, because I adore it. Not so much Phaedra's kind-cool, angular objects-but serious jewels: diamonds, cuffs and chokers, brooches like shooting stars, tiaras. Jean Harlow jewels, Irene Dunne on the ship in Love Affair. Allegra stirred in her leopard-print nest, yawned, and shot out a fist. Phaedra lifted her onto her lap, instantly dipping her swan neck, dropping her face into the orange hair, breathing in her child's scent. An authentic gesture, automatic, unstudied. I felt prickles shoot down my arms. I touched a finger to Allegra's hand, and she gripped it hard and hung on. "You should have one, you know," said Phaedra, harping, and this instantly got my hackles up, until I saw her face, which was something like kind. Phaedra was always a better person with Allegra in her arms. So I just trilled a little laugh and said, breezily, "Me with a baby. Can you imagine?" "Of course, I can. Perfectly," said Phaedra. "And so can you." While I resented her smug smile, and while I'd have died before admitting it to her, I had to admit to myself that she was at least partly right: I couldn't imagine it perfectly, but I could imagine it. Had imagined it, in fact, more than once. But, every time, what brought me to my senses was my conviction that before a person dropped a new life into this world, she should probably get a real one herself. The truth was, I was treading water and had been for some time. If you're wondering why a thirty- something woman who had gone to all the trouble of attending a university and slogging through medieval allegorical texts had risen no higher on the career food chain than café manager, I don't blame you. I wondered myself. And the best answer I'd come up with was that I hadn't figured out anything better-not yet. If I were to ever have a full-fledged vocation, as opposed to a half-assed avocation, I needed to love it and, in my experience, it isn't always easy to figure out what you love. You'd think it would be, but it isn't. Also, if you stay in it for any length of time, like anyplace else, a café becomes a world. I felt suddenly weary, looking at Phaedra and Allegra and the shining black pram. And if a woman weighing less than ninety pounds can be said to heave herself, I heaved myself out of my seat and lugged myself back to my spot behind the bar. All of which is meant to demonstrate the ordinariness of the day and how the ordinariness was even taking on shades of dreariness and futility. Because you have to understand what my life was like in the "before" in order to see just how much it changed in the "after." Ordinary, ordinary. Except that-and I honestly believe this, Linny's pooh-poohing of movie moments notwithstanding-just before, a minute before the café door opened one more time, the ordinary day turned itself up a notch, in preparation. The light falling through the high, arched windows went from mellow to brilliant, turning the old copper of the espresso machine to pure gold. And the music-Sarah Vaughan, whom I worship, singing George and Ira, whom I worship-was suddenly floating and dipping like some kind of bird in the clear space above the cigarette smoke and chitchat. The coffee smelled sublime, the flowers I'd bought that morning pierced the air with their blueness, the coffee cups lost their chips and glowed eggshell-thin, and standing in my red sweater and vintage suede skirt, my boots solidly on the floor, I felt almost tall. The door of Café Dora opened, and Cary Grant walked in. If you haven't seen The Philadelphia Story, stop what you are doing, rent it, and watch it. It's probably overstating the point to say that until you watch it, you will have been living a partial and colorless life. However, it is definitely on the list of perfect things. You know what I mean, the list that includes the starry sky over the desert, grilled cheese sandwiches, The Great Gatsby, the Chrysler building, Ella Fitzgerald singing "It Don't Mean a Thing (If You Ain't Got That Swing)," white peonies, and those little sketches of hands by Leonardo da Vinci. If you have seen it, then you know there's a moment when Katharine Hepburn as Tracy Lord steps from a poolside cabana. She's got a straight white dream of a dress hanging from her tiny collarbones, a dress fluted and precise as a Greek column but light and full of the motion of smoke. A paradox of a dress, a marriage of opposites that just makes your teeth hurt it's so exactly right. I was fourteen when I first saw it. It was three days before Christmas, which in my family's house meant, means, and will always mean, Yuletide sensory overload: every room stuffed to the gills with garland and holly, the whole place booming with Johnny Mathis, and a monstrosity of a tree towering in the living room, weighed down with ornaments of every description, including dozens defying description that my brothers, sister, and I had made in school over the years. Fourteen was not a good year for me. I was the latest of late bloomers, of course, about two feet high and scrawny as a cat, still shopping in the children's department, profoundly allergic to every member of my family, and convinced that nothing could make me happy. But then my grouchy channel-surfing landed me in the middle of a black-and-white heaven: Tracy, the dress. I was so struck, I forgot how to swallow and began to truly asphyxiate on a sip of 7-Up. And when, a little later, Tracy unfastened the belt from her willow waist and slipped her faultlessly formed self out of that faultlessly formed garment, I stood up and yelled, "Holy shit, that's her bathing suit cover-up!" which my father, who was sitting on the floor fastening-no joke-jingle bells to the collars of our cats, did not appreciate. I turned every atom of myself over to the rest of the movie. People must've gone tearing through the room, because people always did go tearing through rooms, especially my brothers Cam and Toby, who were eight and nine at the time. But a volcano could have begun spewing molten rock inches away from me, and I would not have noticed. I sat. I watched. If a girl could sling a poem over her swimwear as though it were an old T-shirt, what else might be possible? I slid my fingers over my face, feeling for Tracy's winged cheekbones. And when Dexter (Cary Grant) took Tracy to task, saying, "You'll never be a first-rate woman or a first-rate human being until you have some regard for human frailty," I recognized it as wisdom and wondered whether I had it, that kind of regard, and just how to get it if I didn't. In college, I took a film studies class subtitled something like "Turning the Formula on Its Head" in which the professor talked about the trick The Philadelphia Story pulls off. It should never have worked: creating a fantastic love scene between two characters whom you know are not in love with each other, getting you somehow to root for them wholeheartedly during the scene, but then to feel completely satisfied when they end up with other people. Before you get the wrong impression, you should know that I'm not and never was one of those film people, the kind who argue into the wee hours about the auteur theory and whether Spielberg is the new Capra, or whether John Huston impacts, in unseen ways, every second of American life. I don't know from camera angles, and I don't have an encyclopedic knowledge of pre-World War II German cinema, but I fell a little in love with the film professor when he looked upon us with shining eyes and proclaimed, "No, it should not work. But work it does!" because he was so passionate and right. When I heard Mike (Jimmy Stewart) say to Tracy in that tender, marveling voice, "No, you're made out of flesh and blood. That's the blank, unholy surprise of it. You're the golden girl, Tracy," I clasped my hands under my pointy chin, prayed that she would run away with him, and swore to God that someday a man would say those words in that voice to me or else I would die. But then, at the movie's end, my father heard cheering and left water running in the sink to watch his lately distant, disaffected teenage daughter bang her fists on the arms of her chair and turn to him crying, "with a face as open as a flower" (my dad's own improbable words), saying breathlessly, "She's marrying Dexter, Daddy." I'll admit it. I've always been more than a little proud of myself for having been fourteen and deeply benighted about almost everything, but having had the sense to recognize what is surely a universal truth: Jimmy Stewart is always and indisputably the best man in the world, unless Cary Grant should happen to show up. His name was Martin Grace. An excellent name, which, you may have noticed, shares all but three letters with "Cary Grant." Of course, if you're not a freak of nature, you probably didn't notice, and you'll be relieved to know that it didn't even spring to my mind right away. It was later, as I lay in bed that night, that I figured it out, mentally crossing out letters with an imaginary pencil, concentrating pretty hard, but sort of affecting an offhand, semi-interested attitude about it, cocking my head casually on the pillow, even though there was no one in the room to see me. Truth be told, I'm a little superstitious about names. Back in college, I dated an enormous, blond, dumb fraternity boy from Baton Rouge with a voice like a foghorn purely on the strength of his being named William Powell, whom everyone knows from the Thin Man movies, but who is even better in Libeled Lady and is one of those men whose handsomeness you believe in completely even though you know it doesn't exist. My mother met the boy and knew instantly what I was up to. "Your nose looks like Myrna Loy's," she'd said. "Be satisfied with that." Even so, I didn't ditch Bill until a few nights later when I stood in his Georgian-mansion-turned-dank-cave of a frat house and watched Bill dancing shirtless on a tabletop, his bare, unfortunate belly pulsating like an anguished jellyfish. The bellyfish pulsated, and William Powell, with a delicate shrug, chose that moment to detach himself from Bill forever and slip out into the honeysuckle-scented night. Slippery things, names. Still: Martin Grace. Good. Very good. He'd stood dark-eyed and half-smiling in the doorway. Tall. Suit, hair, jawline all flawlessly cut. "Imperially slim," is the phrase that jumped out of my fourth-grade reading book into my head. But the man in that poem ended up shooting himself, I remembered later, while this man, my man, clearly had only a seamless, sophisticated, well-shod life ahead of him. I'm exaggerating, but not much, when I say that as he walked to the counter-walked to me-the dogs, chess players, prams, etcetera parted before him like the Red Sea. "Hello," he said, and his voice wasn't mellifluous or stentorian or melting or sonorous but was nonetheless unmistakably leading-man. As you knew he would, he had a dimple in his chin, and for a wild second or two I considered touching it and asking him how he shaved in there, because if you're going to rip someone off it might as well be Audrey Hepburn. I didn't, but I distinctly felt the dimple impress itself upon my unconscious, if such a thing is possible. "Hi" is what I said. "A coffee, please. Black." And you could just tell that's really what he liked and didn't sense a self- conscious backstory involving a Marlboro Man masculinity obsession trailing like a long, stupid tail behind the request. When I handed him his coffee, I let my hand linger on it an extra beat, so that it was still there when he reached for it. I like to pretend to myself that the cup became a little conduit and that our electricity shook it. Anyway, coffee spilled on my hand and I yelped and pressed it to my mouth like a two-year-old. He looked at me with real concern and said, "I should be kept in a cage." "Occupational hazard." I shrugged. "It's fine." "It's fine? Really? Because if it's not, you have to tell me so I can go drown myself in the Delaware." "Don't be silly," I said. "The Schuykill's closer." "The Delaware's deeper. I don't have the guts to drown myself in shallow water, even for you." Even for you, even for you! my heart sang. "Except," he said. "Except what?" I snapped, snappily. "Except it'll have to be the Thames. I leave for London in two hours." This might not sound so earth-shattering to you, so fabulously clever or romantic, but trust me when I tell you that it was. Right from the start, we just had a cadence, an intuitive rhythm that I might possibly compare to the sixth sense that jazz musicians sometimes have when they're playing together if I knew the first thing about jazz. You've seen Tracy-Hepburn movies, yes? It was the conversation I'd been waiting for all my life. And it kept up, that back-and-forth. He talked about his business trip-four days in London, finance something or other-and about fog, how the thing of it was it really was foggy in London. I felt taut and tingly and flushed, as though I were wearing a new skin, but I wasn't exactly nervous. Miraculously, I was up to the challenge of meeting this man, perfect as he was. I was "on." I even had the presence of mind, in the presence of Martin Grace, to continue doing my job, which was fortunate because that's the way life is, isn't it? Even as you and the Embodiment-of- All-Your-Hopes stand percolating your own little weather system, two teenaged boys with skateboards under their arms are bound to walk up, splash a pile of dimes onto the counter, and order triple mocha lattes. And usually, it's not when your eyes are locked with the black-lashed, chocolate-colored stunners the dream man apparently carries around on his face all day as though they were ordinary eyes, but when you're busy jittering the dimes into the cash register that you'll hear him say, "Why don't you come with me?" Because he said that, Martin Grace did. To me. I heard it again, an eerily precise aural memory, as I lay in bed that night, turning over the all-but- three-letters/Cary Grant idea for the first of you don't even want to know how many times. At the sound of Martin's voice in my head, I sat up, got up, walked over to the window, my white nightgown floating like a ghost around me, and sat in the chair I'd covered last spring with figured, lead-heavy green silk that had once been a monster of a fifties ball gown hanging in a resale shop in Buena (pronounced Byoona) Vista, Virginia. I cranked open my third-floor casement window, looked at Philadelphia-my piece of it-and let my affection for it lift lightly off of me like scent from a flower and drift out into the cool air. Spruce Street: cars and lights; the synagogue on the corner; the hustlers in front of it, male and heartbreakingly young. I felt the two tugs I always felt when I looked at those boys: the tug toward wanting the cars to stop, the tug toward wanting them not to stop. I could be in London right now, I thought. Right now, lying back on unfamiliarly English pillows with Martin Grace beside me. Why I wasn't is a long story-so long that it probably isn't a story at all. It's probably just the way I am. But the next thing I said, a major-league clunker, the conversational equivalent of falling on my face, pretty much sums it up. I stood there in tumult, weighing common sense against desire, trepidation against adventure, caution against impulse, while inwardly banging my head against the wall because, tumult or no tumult, my answer was a foregone conclusion: "I want to, but I can't. My mother wouldn't like it." "So we'll leave her home this time. She can come on the Paris trip." As I sat at my window replaying this conversation, lonely, nightgowned, face burning, but still somehow happy, I watched a helicopter in the distance drop its beam of searchlight and swing it slowly back and forth. I imagined a couple in evening dress doing a song-and-dance number in the street below, the woman's skirt blooming like a white carnation as she spun. Then I tried to imagine a world in which my mother would accompany me and my older (by maybe fifteen years?) lover to Paris, and blew out a single, sarcastic, "Ha!" My mother alphabetizes her spice rack, wears Tretorn sneakers, and never puts eleven items on the ten-item express grocery counter, ever. She is a garden club president, and I mean that both literally and figuratively. On the outside, my life doesn't look much like hers; I've made sure of that. But the truth is that I am my mother's daughter, literally, figuratively, forever. Still, I made sure Martin Grace did not walk out the door without my number. I leaned over, folded back his lapel, and placed it in his inside breast pocket myself. Then, I gave him a look so worthy of Veronica Lake, I could almost feel my nonexistent blond tresses falling over one eye. Excerpted from Love Walked In by Marisa de los Santos All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.