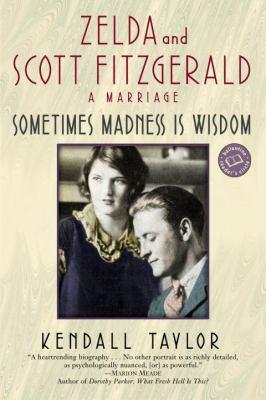

Sometimes madness is wisdom : Zelda and Scott Fitzgerald : a marriage

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Victoria | Available |

Browse Related Items

- ISBN: 0345447166

-

Physical Description

print

xxi, 442 pages : illustrations ; 21 cm --. - Edition 1st trade pbk. ed. --

- Publisher New York : Random House Pub. Group, 2003.

Content descriptions

| General Note: | "Ballantine Books." |

| Bibliography, etc. Note: | Includes bibliographical references (pages 415-423) and index. |

| Immediate Source of Acquisition Note: | LSC 23.95 |

Series

Additional Information

Sometimes Madness Is Wisdom : Zelda and Scott Fitzgerald - A Marriage

Click an element below to view details:

Excerpt

Sometimes Madness Is Wisdom : Zelda and Scott Fitzgerald - A Marriage

Montgomery and All That Jazz Born on Tuesday, July 24, 1900, when her mother was nearly forty, Zelda was the youngest of Anthony and Minnie Sayre's six children. She was named for the gypsy heroine in Robert Edward Francillon's 1874 romantic novel Zelda's Fortune. Describing his heroine, Francillon could have been speaking of Zelda Sayre when he wrote, "Zelda's heart was of July, but her tears were of April, when her sun rose. There was more than a little of Marietta in her besides her trick of stamping on the floor. But it must not be thought that rippling waves are always the sign of a shallow sea. She had her mother's quickness and impulse, but her depths were her own." She was baptized in the Episcopal Church of the Holy Comforter along with her three sisters: Marjorie, the oldest, born in 1882; Rosalind (called Tootsie), eleven years older, born in 1889; and Clothilde (called Tilde), nine years older and born in 1891. Her brother Daniel died of spinal meningitis at eighteen months, which left Anthony D. Sayre Jr., born in 1894, the only boy. By the 1600s, Sayres were prominent on Long Island and then in New Jersey and Ohio. They moved to Alabama in 1819 and became large landowners and prosperous planters, merchants, and respected citizens. Many streets bore their surnames, including a prominent one named for William Sayre, Zelda's great-uncle, who came to Montgomery with his brother Daniel in 1819 and played a leading role in the growth of the town. Daniel became a newspaper publisher in Tuskegee and Montgomery, and his private residence at 644 Washington Street was later used as the first White House of the Confederacy. Zelda's mother's family, from the Scottish MacHen clan, had emigrated to Virginia early in the seventeenth century and changed their name to Machen. They were prominent statesmen, farmers, and politicians. A descendant of early Maryland and Virginia settlers, Minnie Machen's father was an attorney and tobacco planter who owned three thousand acres on the Cumberland River, and represented Virginia in the Confederate Congress. After the Civil War he served as a U.S. senator. The Sayres had always resided in the western section of Montgomery, the oldest part of town, convenient to schools and serviced by the streetcar. While wealthier families built new homes in other sections, many of the old families remained rooted there. Though the Sayres moved several times within that neighborhood, Zelda's childhood was spent at 6 Pleasant Avenue in a rented gray frame house. It was built by one of the Judge's friends, whose family's pre-Civil War plantation had occupied that part of town. The square home faced their landlady's large white house across the street, left to her by ancestors; it was set amid a huge garden dotted with fruit and shade trees, boxwood, crepe myrtle, camellias, and kiss-me-at-the-gate that had been planted before the Civil War. At the rear of the Sayre house was a grassy, field-sized lot bordered by a ravine laced with wild grapevines on which Zelda spent hours climbing, and a great oak tree between whose roots spread carpets of moss on which she played endless games. It was a comfortable house surrounded by a spacious porch curtained with clematis vines and smilax to shield it from the western sun. On one side was a bench and chairs where Zelda and her friends gathered after supper; on the other hung a vine-laced swing where she and her sisters entertained male suitors. The large informal rooms were tastefully papered, and downstairs, furniture was set on polished pine floors centered with rugs. An expert gardener, Zelda's mother placed fresh flowers everywhere, and the rooms were always cheerful with sunlight and color. Tall glass-doored bookcases filled with Daniel Sayre's library lined the hallways. A piano, on which Zelda was given lessons, dominated the living room, on whose walls hung an oil painting of Minnie Sayre's mother and a hand-colored mezzo-tint of Napoleon bidding his wife and infant son good-bye. Zelda's sister Rosalind recalled how "the door was always open to those of all ages, friends of each of us who were always dropping in and were welcome to meals when they wanted to stay for them. Even with his dislike of organized social activity, Papa did not mind this visiting influx but was a gracious host. He was always hospitable to callers who visited his daughters and would say a few words to them before making a hasty retreat." Zelda's room above the porch on the second floor was the smallest and coziest; the sound of the rain hitting the porch's tin roof remained forever in her memory. It was papered in a pink floral design that matched a chintz-covered dressing table, and the view from its two windows, curtained in white muslin, was of the luxuriant gardens across the street. A smoothly woven straw mat covered the floor, and the simple furnishings included a small white desk, slender rocking chair, and white-painted iron bed. The valedictorian of his class at the University of Virginia, Judge Anthony Dickerson Sayre was a formidable man, president of the Alabama State Senate, and a circuit court judge at the time Zelda and Scott met. He later served as associate justice of the Alabama Supreme Court. A brilliant lawmaker--often referred to as "the brains of the bench"--he was famous in legal circles for never having his opinions overturned. He neither smoked nor drank and was usually in bed each night by eight-thirty. Every morning he walked to the corner and caught the tram to the capitol. Because of poor eyesight (which Zelda inherited), he had never learned to drive. "He was considered a great Judge, so much so that when it rained, the conductor of the streetcar which ran down to the Supreme Court building, and which he caught every morning, would stop the streetcar and walk for two blocks with an umbrella to fetch him." Dignified and reserved, he could become an animated conversationalist when the mood struck him, and shared a gentle sense of humor with his family. Though he had many friends, he cultivated no particular intimates. Like Zelda, who was exceptional in the way she drew young people to her, he, too, possessed an affinity for small children. The son of Daniel Sayre, editor of the Montgomery Post and an influential figure in Masonic politics, Anthony Sr. was not interested in acquiring material things. He so disapproved of debt that he refused to purchase a house because it meant carrying a mortgage. Yet, while they never became wealthy, the Sayres always had a cook, laundress, handyman, and, when necessary, a nurse to care for infants. Zelda's nurse had been a large, handsome black woman called Aunt Julia who lived in a small house in the rear yard and dressed in a starched white apron and cap. Totally absorbed in his work, Judge Sayre provided a strong, assuring presence to his family but little warmth or affection. Zelda tried piercing his remoteness by capturing his attention with her antics; when this proved unsuccessful she determinedly sought the attention of other men. Zelda inherited her father's keen intelligence. Her ability to use words and witty metaphors, however, came from her mother, who had aspired to be an actress or opera singer and had studied elocution in Philadelphia during the winter of 1878. Thwarted by her own father, who considered a theatrical career socially unacceptable, Minnie placated her creative ambitions by writing poetry for local newspapers, giving singing lessons, and producing plays and skits for community theater. She wanted her daughters to have the opportunities denied her, and especially encouraged Zelda's creative endeavors by making her costumes for local charity productions and encouraging her interest in ballet. One astute reporter for the Montgomery Advertiser, commenting on Zelda's dancing, observed: "Already she is in the crowd at the Country Club every Saturday night and at the script dances every other night of the week. . . . She might dance like Pavlowa [sic] if her nimble feet were not so busy keeping up with the pace of a string of young but ardent admirers set for her." The paper dispatched a photographer to take Zelda's picture. At fifteen, in a ballerina's tulle dress and ornate headpiece, her arms gracefully uplifted, she already appeared supremely confident. As the youngest child, Zelda was always called "baby" by her parents. Pampered and indulged, she developed finicky eating habits and became petulant whenever food was not to her liking. "I never considered Zelda especially spoiled by Mama, except about food," Rosalind recalled. "If she did not like what the meal offered, she would refuse to eat and become cross or insistent, then Mama would produce something from the icebox or pantry that was acceptable. Not the proper feeding, but it had no bad effect, for she was a healthy child and teenager, stronger than the rest of us." Accustomed to eating only what she wanted and determined to remain slim, she practically lived on tomato sandwiches. On dates, she was partial to midnight suppers of fresh spinach and champagne. The specificity of her culinary likes and dislikes so fascinated Fitzgerald that he later incorporated them into the character of Gloria in The Beautiful and Damned. "There was, for example, her stomach. She was used to certain dishes, and she had a strong conviction that she could not possibly eat anything else. There must be a lemonade and a tomato sandwich late in the morning, then a light lunch with a stuffed tomato. Not only did she require food from a selection of a dozen dishes, but in addition this food must be prepared in just a certain way." Encouraged by a mother who believed she could master anything, Zelda grew fearless in her approach to life, tackling even the most dangerous feats without hesitation. Unconventional and independent, capricious and imaginative, she possessed enormous stamina and performed even the most elementary tasks with competitive drive. Sara Haardt recalled that "She had . . . a great deal more than the audacity or the indestructible vitality of those war generations. In addition, she had a superb courage--the courage that is not so much defiance as a forgetfulness of danger, gossips or barriers." She was drawn to excitement and danger as a child, climbing trees that others shunned, teasing boys mercilessly, and seldom encountering anyone she could not out-distance. Once, when forced to baby-sit her cousin Noonie, she placed the little girl high in the oak tree near the back of her house and said, "Stay right there until I get back." Then she ran off with friends, returning in an hour with a candy stick and the warning, "Don't you dare tell on me." At ten she was interviewed by Tallulah Bankhead's aunt Marie for an article entitled "Children of the Alabama Judiciary" to appear in the Montgomery Advertiser. Describing Zelda as a friendly and candid child, Bankhead took her at her word. Zelda asserted that Robber and Indian were her favorite games because they involved running, and that she admired the Indians for their fearlessness and because they were "such great riders and swimmers." While claiming reading and geography were her favorite school subjects, and drawing and painting favorite pastimes, it is clear that as a child she was always more interested in playing outdoors. A typical tomboy, she'd swing from the magnolia tree in her yard or run barefoot at breakneck speed down the street after a dog. "I was very active as a child and never tired, always running with no hat or coat . . . ," Zelda recalled. "I liked houses under construction and often I walked on the open roofs; I liked to jump from high places . . . I liked to dive and climb in the tops of trees. When I was a little girl I had great confidence in myself, even to the extent of walking by myself against life as it was then. I did not have a single feeling of inferiority, or shyness, or doubt, and no moral principles." One of her favorite pranks was to call out the fire department on false alarms. She once telephoned the fire station to say her cousin Noonie was stuck on the roof, then climbed up herself so they would have someone to rescue. Younger by nine years than her nearest sister and six years younger than her brother, Zelda was never really close to any of her siblings, but saw more of Rosalind than anyone else. Both Tootsie and Tilde were attractive and popular in Montgomery society long before Zelda. Tilde was a classic beauty with lovely soft-cut features, creamy skin, and large dark eyes, but reserved. Marjorie was artistically inclined and excellent at pen-and-ink drawings. But she was a sickly child and prone to depression during much of her life. Anthony was as mischievous as Zelda and always a troublemaker; at two years old, he lined the chamber pots up on the front porch and filled them with coal to welcome the governor's wife. Also a talented artist, he became an aimless and rebellious youth who dropped out of Auburn, suffered a nervous breakdown, and eventually took his own life. He was the third member of Zelda's immediate family to do so: Zelda's maternal grandmother and her sister had both committed suicide. When Zelda entered high school there were no other children living at home. Anthony was employed in Mobile as a civil engineer. Rosalind, after working for six years as society editor and general reporter for the Montgomery Journal, had married Newman Smith. Marjorie had quit teaching school to marry Minor Brinson. As the first girl from a respected family to take a job other than teaching, Clothilde raised eyebrows by working as a teller in the First National Bank, where men lined up outside to stare at her. She held that job until marrying John M. Palmer. Compared to her more stylish sisters, Zelda was uninterested in clothes or fashion. "During those days, she cared very little for clothes, was even slouchy at times," one classmate recalled. "Her two older sisters were 'out' and the new clothes and family's attention went to them. Zelda's dresses were often hand-me-downs. Maybe that is why she preferred to wear her middy blouse and skirt, the uniform of high school girls at the time. However, if she had cared enough for pretty clothes to demand them, she could have had them, I'm sure. Old Judge Sayre, as we called him, was comfortably fixed. They lived in a big two-story home just off Mildred Street. Judge Sayre was always immaculately dressed and dignified; Mrs. Sayre seemed to be a nonconformist." Since childhood, Zelda had always dreamed of becoming a ballerina. She began taking dance lessons at the age of six and continued training with several good teachers. In 1917 she enrolled in a new dancing class offered by Professor Weisner, a talented coach who had suddenly appeared in the city. "The Gentiles thought he was Gentile and the Jews thought he was a Jew; and no one could say where he had come from or why a dancing master as talented as he should come to Montgomery." Under his skillful tutelage, Zelda starred in numerous pageants and entertainments, receiving top billing in ballet recitals at the Grand Theatre. The Montgomery Advertiser of 1917 noted one such performance: "A feature of the evening was the exquisite solo dance given by Miss Zelda Sayre, a pretty and popular member of the younger set. Miss Sayre wore a costume of blue and gold tarleton, and gave the dance in a spotlight." Another event did not go as well. Sara Haardt recalled how, portraying Mother England in a wartime pageant, "in a resplendent costume of crimson and white, with a shining helmet and sword, [Zelda] marched on the stage and faced the tense, waiting crowd. The moment before, in the dressing-room, she had recited her speech letter perfect: '. . . Interrupted in these benevolent pursuits for over three years, I have been engaged in bloody warfare and the end is not yet. O, America, young republic of the West, blood of my blood and faith of my faith, for humanity's sake together we fight! . . . The Stars and Stripes on the battle lines of glorious France have strengthened my hand and filled my heart with cheer. In this hour of great peril, the young manhood of your great Republic is needed in all its strength!' But now, as she stood there, her tongue was suddenly paralyzed. 'Interrupted--' she began. 'Interrupted--' she began again. 'Interrupted-- It was hopeless. With a shrug of her shoulders, she said in a clear voice, 'I'm sorry, I've been permanently interrupted,' and walked off the stage with great dignity." From the Hardcover edition. Excerpted from Sometimes Madness Is Wisdom: Zelda and Scott Fitzgerald: A Marriage by Kendall Taylor All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.