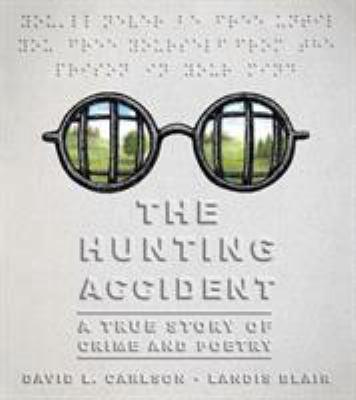

The hunting accident : a true story of crime and poetry

It was a hunting accident that much Charlie is sure of. That's how his father, Matt Rizzo--a gentle intellectual who writes epic poems in Braille--had lost his vision. It's not until Charlie's troubled teenage years, when he's facing time for his petty crimes, that he learns the truth. Matt Rizzo was blinded by a shotgun blast to the face but it was while participating in an armed robbery. Newly blind and without hope, Matt began his bleak new life at Stateville Prison. In this unlikely place, Matt's life and very soul were saved by one of America's most notorious killers, Nathan Leopold Jr., of the infamous Leopold and Loeb.

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Victoria | Available |

Browse Related Items

| Genre |

| True crime comics. Graphic novels. Comics (Graphic works) Novels. |

- ISBN: 9781626726765

-

Physical Description

print

437 pages : chiefly illustrations ; 24 cm - Edition First edition.

- Publisher New York : First Second, an imprint of Roaring Brook Press, 2017.

Content descriptions

| General Note: | GMD: graphic novel. |

Additional Information

Publishers Weekly Review

The Hunting Accident : A True Story of Crime and Poetry

Publishers Weekly

(c) Copyright PWxyz, LLC. All rights reserved

The subtitle barely captures the scope of this ambitious debut graphic novel, a mix of biography, history, social commentary, literary analysis, and more. It's a multilayered exploration of the lives of Charlie Rizzo and his father Matt, a blind man with secrets. Charlie's parents separated when he was young, but his mother's death brings him back into his father's life in Chicago. When Charlie becomes involved with petty criminals, Matt begins to reveal his past to his son, and this sweeps through the book like a tsunami of surprises and pure, dark emotion. Matt's story involves a world of gangsters, too, but also jail, the truth of how he was blinded, and an unexpected pivotal person: thrill killer Nathan Leopold Jr., who shared his jail cell. Blair's exceptional pen-and-ink work, which mixes the tangible world with the psychological, brings all the strands together seamlessly and powerfully. (Sept.) © Copyright PWxyz, LLC. All rights reserved.

BookList Review

The Hunting Accident : A True Story of Crime and Poetry

Booklist

From Booklist, Copyright (c) American Library Association. Used with permission.

*Starred Review* This account of two youthful offenders, father and son, at either end of the 1930s-1960s heyday of Chicago's Little Italy brilliantly merges novelistic character development and expressionistic visual presentation (Blair's such a master of crosshatching that he makes Edward Gorey look like an amateur). The siren call of gangs and, ultimately, the Mafia was too much for either Matt Rizzo or his son, Charlie, and each got in trouble before turning 21. When Charlie faces probation, his father finally comes clean about the origin of his blindness. Instead of the hunting-accident story he's told Charlie for years, Matt actually lost his vision in an armed robbery that got him locked up, where he shared a cell with Nathan Leopold, one of the thrill killers who murdered 14-year-old Bobby Franks in 1924 in the crime of the century. Leopold recognized Matt's intelligence, coerced him to learn Braille, made him his assistant in the classes he taught in prison, and motivated him toward the straight life he attempted upon parole. That life was disrupted in ways that affected Charlie, and the unique achievement of the book is how Carlson and Blair depict the tangled webs of half-truths and lies both men had woven around themselves and the mingling pasts of father and son. A true story epic in scope and arrestingly told.--Olson, Ray Copyright 2017 Booklist

School Library Journal Review

The Hunting Accident : A True Story of Crime and Poetry

School Library Journal

(c) Copyright Library Journals LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Media Source, Inc. No redistribution permitted.

After his mother died, young Charlie Rizzo moved in with Matt, his blind, insurance-selling father in Chicago. When Charlie discovered as a teenager that his father wasn't blinded in a hunting accident, as he'd always thought, Matt decided to come clean and reveal the real story, which involved the Chicago mafia and armed robbery. Matt told Charlie that he eventually went to prison in 1931, where, under the guidance of infamous murderer Nathan Leopold Jr. (who, with Richard Loeb in 1924, kidnapped and killed a teenage boy), he developed a love of literature. This true account of gangster Matt Rizzo includes some of his prison artifacts, as well as snippets of his writing. The comic pays homage to Dante's Inferno and other works, showing how those allegories are still relevant. Blair's illustrations are stark and extremely detailed, and the book design is a masterpiece, complete with a ribbon marker and the title duplicated in braille on the cover. VERDICT While some teens may skim over the more "literary" portions, others will delight in this graphic homage to Dante. Perfect for inclusion on AP or college reading lists.-Sarah Hill, Lake Land College, Mattoon, IL © Copyright 2018. Library Journals LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Media Source, Inc. No redistribution permitted.

New York Times Review

The Hunting Accident : A True Story of Crime and Poetry

New York Times

December 3, 2017

Copyright (c) The New York Times Company

FOR 44 YEARS, Ernie Bushmiller's "Nancy" was the most meat-and-potatoes strip on the funnies page, a streamlined and glistening machine for delivering one dopey gag every day, no more and no less. "Dumb it down" was one of Bushmiller's mottos; in practice, as Paul Karasik and Mark Newgarden point out, that meant applying the sizable arsenal of his craft to making sure every mark in each strip served its central joke. Their book how to read nancy (Fantagraphics, paper, $29.99) is a comprehensive, scholarly and intensely goofy dissertation on a single daily "Nancy" strip from 1959, in which Nancy's pal Sluggo is spritzing people with a water pistol and growling "draw, you varmint," while she prepares to blast him with a garden hose. The core of the book is a 44-part analysis of each individual element of that strip and the artistic considerations behind it, from the way Sluggo's cap interrupts the contour of his final word balloon to the precise number of droplets emerging from a water spigot (four): "When these drips are taken together with the previous panel's spritzes, a mental image is constructed of Sluggo demolished in a fulsome blast of liquid comeuppance." Karasik and Newgarden augment their argument with extensive historical context for that August morning's "Nancy" strip. The book features an illustrated biography of Bushmiller, explaining how he took over Larry Whittington's feature "Fritzi Ritz" in 1925, and how Fritzi's frizzy-haired niece Nancy, introduced in 1933, got the strip renamed after her five years later. One of many appendixes is an extended history of the "water hose" gag from its origins in belle epoque Parisian cartoons through its appearance in an early Louis Lumiere film; another one catalogs other "Nancy" strips with similar elements. And the late Jerry Lewis, of all people, supplies a four-sentence foreword - as in Bushmiller's art, the gesture alone makes it funny. A nearly-400-page graphic memoir by a 21-year-old seems like a dicey proposition - not least because most cartoonists take years or decades to develop their voice - but Tillie Walden's SPINNING (First Second, paper, $17.99) IS an engrossing, gorgeously quiet look back at the 12 years she devoted to figure and synchronized skating. It's also her fourth book, remarkably. Walden touches on the physical control the sport requires and on the rivalries and camaraderie of young skaters, but she's more concerned with evoking the feeling of being a skater: the chill of earlymorning wake-ups (she recalls sleeping on top of her blankets so that she'd be cold already by the time she arrived at practice), the openness above the ice in an empty rink, the long stretches of waiting punctuated by brief flashes of performance. "Spinning" gradually reveals itself as a coming-out story, too. "A teacher's aide had shown me how to hold your sleeve when you put your jacket on," Walden writes. "1 still remember her hands on my shoulders. 1 didn't have a word to describe it yet, but in that moment 1 knew." When she meets her first girlfriend, we see them nervously watching a video on "how to kiss a girl" together. Walden evokes emotional states with elegantly composed panels: minimal, tentative lines, more delicate than a blade's, surrounded by bold swatches of negative space. (The entire book is printed in a chilly dark purple ink, except for a few passages in which a solid, pale yellow stands in for sunlight or electric light.) After a sexual assault, she finds herself drifting through life for a while, and the narrative shifts to disconnected, full-page images. Later, a crucial competition appears as a fusillade of little panels, with tiny drawings of Walden in motion alternating with transcriptions of her fragmented thoughts. The premise of Matthew Rosenberg and Tyler Boss's 4 KIDS WALK INTO A BANK (Black Mask, paper, $14.99) IS delICIOUSIy twisted: A smart, angry 12-year-old girl named Paige discovers that her father's former criminal associates are forcing him to help them rob a bank, and decides to save him by robbing it herself first, with the aid of her three role-playing game buddies. But the story is mostly a showcase for Rosenberg and Boss's Looney Times formalism, from its Saul Bass-style cover design onward. Characters are introduced with captions detailing their stats ("Getaway driver with an 85 percent success rate. +2 Dexterity") ; action scenes are drawn as diagrams, and conversations as RPG fantasies; the sound effects for a pair of handcuffs closing and opening are "BUSTED" and "UNBUSTED." For every experiment that works, there's one that flops, which still leaves three or four successes on any given page. All of that fun, though, is in the service of the sucker punch tonal shifts that arrive whenever "4 Kids" seems to be going in a predictable direction. This is a tragedy trying to avoid recognition by wearing a disposable comedy mask. Paige thinks she's in an I-love-it-when-a-plancomes-together heist story, but she's actually in an everything-goes-horribly-wrong heist story. And her friends, having grown up on tales where plucky kids can play detective (or criminal) and save the day, aren't prepared for what happens when blood starts flowing. A very different sort of story of youth derailed, the Australian artist Campbell Whyte's exuberant debut graphic novel, home time (Top Shelf, $24.99), turns "magical realm" tropes inside out. It begins as a vacation romp, with a cluster of half a dozen friends hanging out during their last summer before high school. Then the story takes a sharp turn: The kids fall into a river, and emerge in a seemingly utopian fantasy land, populated by tiny, cheery, treehousedwelling peach people who regard them as divine spirits and induct them into their culture. Mostly, that involves brewing artisanal teas, singing cute little songs about stasis and contentment, and persuading plants to grow into useful shapes. (Oh, and also not venturing beyond the wall that's supposedly there to keep out predators.) It's a richly imagined world, and Whyte immerses readers in it - every so often, the plot pauses for a few pages so he can silently survey the flora, fauna and habitats of a particular area, or explicate some aspect of peach civilization. At first, the kids are desperate to figure out what, exactly, their role in this sugar-buzz "My Little Pony" scenario is supposed to be, and to get back to the real world. As the months pass, though, they acclimate to the peaches' way of life, and find themselves beginning to forget their old reality, until an abrupt ending suggests that a future volume will bring them home, or at least give them a new perspective. (The story gently implies that this isn't the sort of paradise you can come back from.) Whyte draws the early "real-world" section as pencil sketches with a pale sepia tint behind them, and adopts different full-spectrum techniques for the sequences focusing on each of the human youths in the Forest of the Peaches: the flat-colored line drawings of animation cels, the crinkly 8-bit pixelations of old "Legend of Zelda" games, and finally blended paint-on-canvas tones. If "Home Time" hints at a "Peter Pan" situation, the WENDY PROJECT (Super Genius, paper, $12.99), by the writer Melissa Jane Osborne and the artist Veronica Fish, explicitly spells one out, with a similar visual approach. Wendy Davies, 16 years old, was behind the wheel for an accident in which she lost her brother Michael, and his body hasn't been found. Tormented by guilt, she can't bring herself to admit that he's dead, and retreats into a fantasy in which he's been spirited away to J.M. Barrie's Neverland, drawing her visions in a notebook given to her by her therapist. Fish draws Wendy's actual surroundings in jagged, splintery black lines and gray wash. Wherever the "Peter Pan" fantasy turns up, though, her artwork blooms into color, suffusing Wendy's dreams of Neverland and tinging the elements of the real world that she's charged with her hopeful imaginings. Osborne doesn't quite pull off the grand statement about grief and creativity that her story seems to be attempting to make, but Fish's inventive, dramatic staging is striking in its own right. The Austrian cartoonist Ulli Lust's first graphic novel, "Today Is the Last Day of the Rest of Your Life," was autobiographical; her second couldn't be much less so. voices IN THE DARK (New York Review Comics, paper, $29.95) IS Lust's controlled, eccentric adaptation of a 1995 German novel by Marcel Beyer (published in English as "The Karnau Tapes") about the collapse of the Nazi regime and the willful ignorance on which it fed. As with Beyer's novel, it alternates the points of view of Hermann Karnau, a (fictional) sound-recording engineer in World War Il-era Germany, and Helga, the oldest of Nazi Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels's six children (their last name, coyly, never appears in the text itself). Karnau is fascinated with recording and studying human voices, and with collecting curious examples on reelto-reel tapes and shellac discs: "This here, open vowels impinging on gutturals, is a youngster in his death throes losing all vocal control." His is a pseudoscientific curiosity untempered by any moral concerns; that makes him useful to Goebbels, whose inner circle he joins. (As we eventually learn, despite his constant bloviations about the meaning of voice, Karnau doesn't even understand the full range of sound all that well.) His young friend Helga, on the other hand, is too sheltered to grasp what's going on around her - although she's beginning to get a sense of it in the second half of the book, which largely takes place in the last 10 days of her life, in Hitler's bunker in the spring of 1945. Lust counterposes the children's genteel hiking trips and war games with the atrocities Karnau dispassionately documents, drawing both narrators' segments to emphasize visual details over their context. Bodies are seen so close up that they become abstract masses of lines, like Lust's renderings of acoustic phenomena; faces are flattened into grotesque caricatures; scenes are half-obscured by tints that change from section to section - rusty purple, rusty orange, rusty green. THE HUNTING ACCIDENT: A True Story of Crime and Poetry (First Second, $34.99), written by David L. Carlson and drawn with graphomaniacal fervor by Landis Blair, begins with a lengthy feint: It purports at first to be about the relationship between its narrator, Charlie Rizzo, a young Chicagoan in the late 1950s who's gotten in trouble with the law, and his blind, literature-loving father, Matt. Nearly a hundred pages in, it turns out to be something else entirely: the story of Matt Rizzo's extraordinary turnaround. An eighth-grade dropout blinded in an armed robbery he helped commit, he was sent to Illinois's Stateville Prison in 1936, and shared a cell with Nathan Leopold - the upperclass thrill-killer whose murderous partnership with Richard Loeb had been a media sensation a decade earlier. Rizzo wanted only to die, so Leopold made an unlikely deal with him: If Rizzo would learn Braille and read Dante's "Inferno," Leopold would help him commit suicide. The elder Rizzo was, naturally, saved by his newly developed passion for literature, going on to become an enthusiastic if unpublished writer. The lengthy prison drama he narrates to Charlie builds to a climax with suspiciously tidy symbolism, involving a burning library and a ceiling that opens to reveal the sky. The chief pleasure of this book, though, is Blair's artwork, which slathers on patterns, scribbles and frantically detailed cross-hatching of various densities, with only a few flashes of light to breathe air into most pages. (A few entr'actes superimpose silhouettes and blocks of Matt Rizzo's writing upon a background of Braille dots.) He crams every scene with visual metaphors and allusions: In a sequence where Leopold and Rizzo are discussing the story of Dante's damned lovers Paolo and Francesca, the killer's explanations are superimposed on images of fratricides and lovers in the style of Greek pottery, and overseen by the hulking, empty-eyed figures that represent the specters of Leopold and Loeb as Rizzo imagined them in his youth. Daphne, the narrator of Deb Olin Unferth and Elizabeth Haidle's I, PARROT (Black Balloon, paper, $18.95), IS not quite in hell, but she's having a purgatorial moment. The apartment where she lives with her son Noah (when she has custody of him) is "a way station where we wait until there is enough room in hell for us ... They have to expand it down there, put on an addition, get some housepainters in there to fix it up." Still raw from a divorce and trapped by an economy whose cruelty is never far from the story's surface, she's found a gig taking care of a house full of rare parrots for a "positive thought" guru who's taught them to repeat clichéd affirmations ("Practice gratitude! Caw!"). But she doesn't have much to be grateful for: She's got a mite infestation, a boyfriend who can't keep a job, and perpetual friction with her ex-husband's new wife, who's convinced that Daphne can't do anything right for Noah ("The last time he was with you he lost two pounds"). Unferth is best known as a prose fiction writer, and her language is sly and bitterly funny, matched in mood by Haidle's monochromatic, inkwash-style artwork, which plays up the story's whimsy as well as its sadness. Its characters and settings are presented as something like layered cut-paper silhouettes, and the birds who populate the book are sometimes detailed, sometimes the simplest of abstractions. The stripes of a cage's bars perpetually appear in one guise or another. Everything about the birds' presence suggests freedom, and everything about taking care of them traps Daphne a little more. Douglas WOLK is the author of "Reading Comics: How Graphic Novels Work and What They Mean." He writes frequently about comics for The Times.