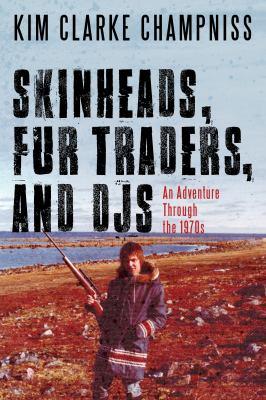

Skinheads, fur traders, and DJs : an adventure through the 1970s

Skinheads, Fur Traders, and DJs is the true story of a precocious, pop-loving teenager who, in the early 1970s, went from London's discotheques to the Canadian sub-arctic to work for the Hudson's Bay Company. His job? Buying furs and helping run the trading post in the settlement of Eskimo Point, Northwest Territories (population: 750). That young man was Kim Clarke Champniss, who would later become a VJ on MuchMusic. His extraordinary adventures unfolded in a chain of "On the Road" experiences across Canada that led him to Vancouver, where he became a nightclub DJ at the height of the disco craze. His mind-boggling journey, from London, to the far Canadian North, to the spotlight, is the stuff of music and TV legends. Kim brings his incredible knowledge of music and pop culture and the history of disco music weaving them into this wild story of his exciting and uniquely crazy 1970s.

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Victoria | Available |

Browse Related Items

- ISBN: 9781459739239

-

Physical Description

print

200 pages : illustrations, map ; 23 cm - Publisher Toronto : Dundurn, 2017.

Additional Information