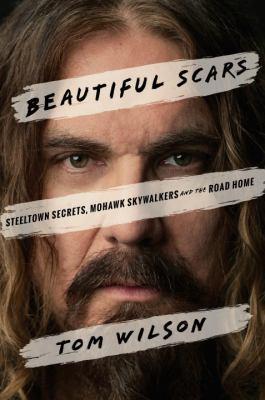

Beautiful scars : Steeltown secrets, Mohawk skywalkers and the road home

"Bunny told me there were secrets about me that she would take to the grave, secrets that no one would ever hear, including me ... ". Tom Wilson always felt something wasn't quite right. His parents, Bunny and George, were much older than other kids' parents. There were no baby photos of him in the house. At school, classmates called him Indian, despite his parents' Irish-Quebecois background. And as he got older, friends, lovers and even family members remarked on his uncanny resemblance to Bunny's closest relative, her niece Janie Lazare, whose father was a Mohawk from Kahnawake, Quebec. Tom wouldn't learn the truth about his identity until he was fifty-three, when a tour handler whose mother had known Tom's now deceased parents let it slip that he was adopted. It would be another two years until he worked up the courage to confront Janie with what the handler had told him, what all his life he had suspected. Janie--the woman whom Tom called cousin, whom he'd known his whole life, who had lived with Tom and Bunny after George died--immediately broke into tears and confessed. She was his biological mother. In this incredible story about family and identity, carefully guarded secrets and profound acts of forgiveness, Tom Wilson writes about growing up as an outsider in two families--the family he lost, and the family who took him in. His story takes us from working-class Hamilton of the 1960s and '70s, neighbourhoods peopled by fall-guy wrestlers, broke mobsters and WWII vets, to today, as he continues his journey to connect with the man he now knows to be his father and with his Mohawk heritage and relatives, discovering Kahnawake chiefs, Brooklyn "skywalkers" and nomadic Arnold Palmer groupies among them. With a rare gift for storytelling and a remarkable story to tell, Tom Wilson writes with unflinching honesty and extraordinary compassion about his search for identity and for the truth about his family. Moving, captivating and at times hysterically funny, Beautiful Scars is a story about the families who raise us, and the families who course through our veins.

Available Copies by Location

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Community Centre | Available |

Other Formats

Browse Related Items

| Subject |

| Wilson, Thomas F., 1959- Wilson, Thomas F., 1959- > Family. Birthparents > Ontario > Hamilton > Identification. Adopted children > Ontario > Hamilton > Biography. Mohawk > Ontario > Hamilton > Biography. |

| Genre |

| Biographies. Autobiographies. |

- ISBN: 9780385685658

-

Physical Description

print

229 pages : illustrations ; 24 cm - Publisher Toronto : Doubleday Canada, [2017]

- Copyright ©2017

Additional Information